Decoding the Chinese consumer

Updated: 2012-08-10 08:56

By Andrew Moody (China Daily)

|

||||||||

As spending slows, fresh focus on shoppers expected to drive global and Chinese economies

This still largely faceless individual is seen as providing life support to the stuttering economies of Europe and prodding the nascent recovery in the United States.

He or she is also key to the Chinese government's plans to move the world's second-largest economy from being export-oriented to more consumer driven.

|

||||

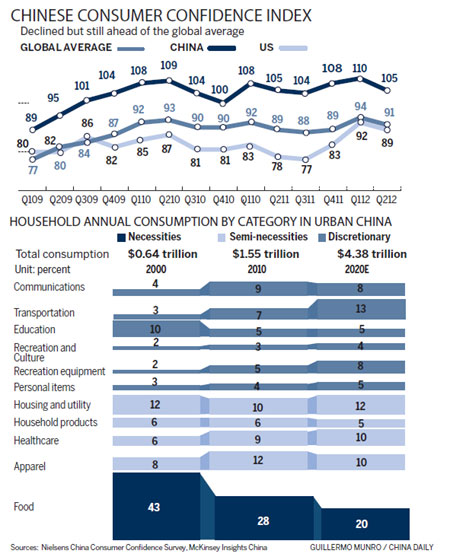

China's consumer confidence index, according to data published earlier this month, showed a marked decline from 104.2 in May to just 99.3 in June.

With spending showing signs of drying up, there has been evidence of a price war in China with Gome, a leading domestic electronic retailer, offering 50 percent online discounts and even McDonald's slashing the price of its value dinner to 15 yuan ($2.35, 1.90 euros).

This weakening in the consumer mood was also detected by global information company Nielsen in its China consumer confidence survey published earlier this month.

It showed confidence slipping five index points in the second quarter to 105 from 110 in the first three months of the year, although the confidence level was still 14 points ahead of the global average.

Yan Xuan, president of Nielsen Greater China, insists it is important not to be alarmed at the latest data.

"What we have seen is a slight decrease but the overall ranking of Chinese consumer confidence is still very high compared with the global average," he says.

Although recent confidence may be ebbing, the Chinese consumer continues to show different characteristics to his or her Western counterpart; and some of that difference is explained by the Chinese being relatively new to consumption.

In its modern history, China has only been a consumer society by any Western definition since the mid-1990s.

Yuval Atsmon, a principal in management consultant McKinsey & Co's Shanghai office and co-author of its recent report Meet the 2020 Chinese Consumer, says a lot of behavior is a result of China being a freshly born consumer society.

"People who are in their 40s and 50s now have not grown up with consumption unlike people in the West. They are not used to being able to afford a car or a computer. There is a lot of discovery going on," he says.

Other developing nations are new to Western-style consumption but do not show the same patterns of behavior as the Chinese.

In Boston Consulting Group's recent annual consumer sentiment survey, 53 percent of Chinese consumers say they plan to trade up, compared to just 29 percent of people in India. Only 18 percent in the US and 13 percent in the EU planned to do the same.

In the same survey Chinese consumers were the most optimistic in the world, 83 percent believing their children would have a better life than themselves, more again than India where 65 percent felt similarly. Just 21 percent in the US and 13 percent in Germany had such a confident outlook.

Carol Liao, partner and managing director of Boston Consulting Group, based in Hong Kong, says this optimism and the desire to buy better products and services marks the Chinese out from the rest.

"That sense of optimism comes out very strongly in our survey and it is a consistent pattern year after year. China is always the No 1 country when it comes to trading up and looking forward to the future."

With Chinese consumers weighed down with shopping bags increasingly visible on London's Oxford Street and New York's Fifth Avenue, one could be left too easily with the impression the Chinese are consumption crazy.

But this is not reflected in the overall statistics. The Chinese are still a nation of savers.

Retail sales have lagged the pace of growth of the economy, according to official data, by 16.9 percent a year over the past decade, partly as a result of wages not rising in line with GDP growth and also greater affluence leading to a greater proportion of saving.

As a result, consumption spending in China is only about 35 percent of GDP, about half of that in the US.

"Don't expect this savings culture to change radically. You might expect to see signs of that changing in the most advanced cities in China such as Beijing and Shanghai but so far we have not," says Atsmon at Mc-Kinsey.

Nonetheless, Chinese buyers of items such as luxury goods have been something of a phenomenon.

Many top stores in European capitals employ Chinese-speaking staff and have even installed China UnionPay payment devices so Chinese can buy goods with their own domestic bank cards.

Tom Doctoroff, chief executive officer Greater China and North Asia Area director for advertising agency J. Walter Thompson, based in Shanghai, says the desire for luxury brands reflects the fact that Chinese consumers can be summed up as "ambitious".

"The Chinese are almost uniquely ambitious when it comes to buying luxury brands, even more so than the Japanese. They almost see such purchases as a declaration of intent and a down payment on their future," he says.

"It is not just young affluent professional people making such purchases but people who are still not making a lot of money."

An odd quirk of the China luxury goods market is that it is the only one in the world where men, and not women, make the most purchases despite the sometimes hysterical focus on Prada and Dolce & Gabbana handbags.

Doctoroff says this is because in China such goods are used as commercial gifts.

"Luxury is seen as a tool of trust lubrication and they are therefore exchanged as gifts," he says.

But Atsmon says it is wrong for outsiders to see luxury goods as a microcosm of the China consumer market.

"You might have some luxury jewelry brand selling, for example, that has three or four stores in London and each of them makes five sales to Chinese people in a day," he says.

"That might translate to 1,000 in a year. It might be a pretty big deal for the brand and grabs all the attention but those kind of numbers are small in comparison to what hundreds of millions of Chinese consumers are doing at home."

Doctoroff, who is also the author of What Chinese Want, Culture, Communism and China's Modern Consumer, argues there are fundamental differences between Chinese and Western consumers.

|

Carol Liao, partner and managing director of Boston Consulting Group, says the desire to buy better products and services marks the Chinese out from the rest. Yong Kai / for China Daily |

|

Mike Bastin, a researcher at Nottingham University's School of Contemporary Chinese Studies, says there is more independent consumer behavior in China. Kuang Linhua / China Daily |

"In the West we are encouraged to define ourselves as individuals. In a Confucian society like China it is not like that. Individuals don't exist outside of their responsibilities to other people, whether it be their family or friends," he says.

He argues therefore that the motivations behind purchases are often different in China than in the West.

"If you take BMW, for example, it is positioned around the world as the ultimate driving machine which is all about the pleasure and thrill an individual will get out of the motion," he says.

"In China buying a BMW would be a reflection of your own power and a status symbol. How others see you rather than your individual pleasure."

But Mike Bastin, a leading expert on Chinese brands and a researcher at Nottingham University's School of Contemporary Chinese Studies, believes the differences between Western and Chinese consumers are no longer so clear cut.

"I think there is actually more independent consumer behavior that is less dependent on either society or family pressures. Chinese consumer behavior is now much more of a hybrid between Chinese and Western culture," he says.

One intriguing aspect of the consumption market is the increasing influence of women.

According to the recent McKinsey survey, participation by women in the workforce on the mainland is 67 percent, more than the 58 percent in the US, 48 percent in Japan and just 33 percent in India. It is also far higher than the 52 percent in Hong Kong.

Liao at BCG says women often play a major role in the spending decisions of households in all markets but in China independent women are increasingly making their own mark.

"In the Western world a man might buy a diamond for a woman as a gift but in China quite a high proportion of diamonds are bought by women themselves. It is not that they can't wait for diamonds to be bought for them. They may just want more," she says.

All this is taking place in an environment where a savings culture still remains dominant.

If the Chinese are such big savers, it begs the question as to what types of expenditure they are foregoing.

Atsmon at McKinsey says it varies depending on the consumer.

"It is really hard to say. Even within a single province there are a lot of differences. In Guangdong, for example, you find that in Shenzhen people do a lot of outside dining, whereas in nearby Guangzhou, people do much less of that," he says.

A major interest of Chinese companies and foreign multinationals is the gray yuan with China facing one of the severest ageing demographics in the world. By 2050, one in three will be aged over 60.

Unusually in China, the people with the real spending power now are in their 30s and 40s and within the next 30 years this is likely to translate into older people being the biggest spenders.

"There is going to be a lot of expenditure on healthcare and there is also going to be a focus on health food products and low fat diets. Today's major consumers are going still be the main consumers in the future but they will be obviously older," Liao at BCG says.

For now, however, the younger generation seems to be obsessed with the latest gadgets with people often lining up around the block at Apple stores when a new product has been launched.

But Atsmon at McKinsey & Co is not sure whether that makes them any different to consumers in the West, where Apple stores are often packed also.

"I would still question whether it is just a question of supply and demand. There are fewer stores and to a certain extent such products have a greater novelty so they attract more attention," he says.

With China being a new consumer market it is often difficult to detect what are the actual Chinese characteristics of behavior and those that are common to all developing markets.

Liao at BCG says Chinese people are currently only behaving in a way similar to the way consumers behaved in the markets around China 100 years ago.

"They are very much into value for money. They like brands but they are not brand loyal. They want a bargain and they will shop around to get it. This is probably deep in the Chinese culture," she says.

Deng Zhangyu contributed to this story.

andrewmoody@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily 08/10/2012 page1)

Relief reaches isolated village

Relief reaches isolated village

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Earth Day marked around the world

Earth Day marked around the world

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Chinese fleet drives out Japan's boats from Diaoyu

Health new priority for quake zone

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

Russia criticizes US reports on human rights

China, ROK criticize visits to shrine

Sino-US shared interests emphasized

China 'aims to share its dream with world'

Chinese president appoints 5 new ambassadors

US Weekly

|

|