A different kind of fighting in Iraq

Updated: 2012-04-13 08:08

By Mohamad Ali Harissi in Baghdad (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

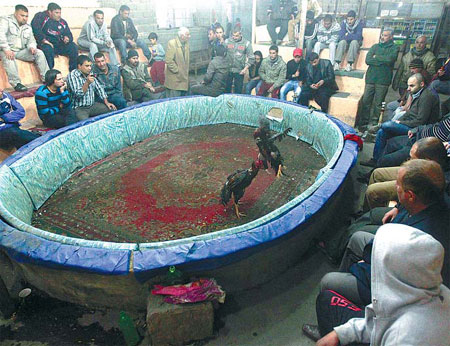

Iraqi citizens watch a battle between two cocks in the fighting arena of a cafe in Baghdad on March 3. Hundreds of dollars change hands in daily betting, even though gambling is considered un-Islamic. [Ahmad Al-Rubaye / AFP] |

Iraq is no stranger to battles, but this is not one fought with rifles and rockets: When the bell sounds, trainers release two cockerels, Daqduqa and Sammam, into the ring.

The crowd, scattered across the makeshift stands in a dank Baghdad house, erupts into cheers, baying for blood.

Welcome to cockfighting in Iraq.

The matches, illegal in Iraq but still widespread, consistently see dozens of men in attendance, some of whom come to gamble and some just for the entertainment.

"I have been coming here for five years, at least once a month," said Ahmed Jabbar, alluding to the fact that even during the capital's brutal violence in 2007 and 2008, he was a regular.

"I never put down money, I just watch this is my favorite sport, more than football or anything on television," said the 43-year-old plumber.

In the small house with a metal roof in west Baghdad, organizers hold cockfights most days from 5 p.m. to 11 p.m., though matches are held in the morning on Fridays, the Muslim day of prayer.

There are no matches from June through October, though, because of Baghdad's boiling temperatures.

The "arena", comprising a circular ring around three meters in diameter, is covered in red carpet and surrounded by tiered seating. A large poster hanging on one of the walls outlines the rules: Each fight consists of eight rounds of 13 minutes, with two-minute breaks between rounds, totaling nearly two hours.

A rooster is considered to have lost if it concedes three consecutive rounds. A win is tallied if one cock holds the other's neck to the ground for a full minute.

Each bird's owner can forfeit a match by pulling his cockerel out if he fears for its life.

And with the competitive juices flowing, the stakes can be high.

In a country where the World Bank puts annual income per capita at $2,340 and unemployment at 17.5 percent, a rooster can cost as much as $8,000. Hundreds of dollars change hands in daily betting, even though gambling is considered un-Islamic.

'Cockfighting brings people together'

The most-prized birds are described as Harati, meaning they are of Turkish or Indian origin, and feature muscular legs and necks, with their owners and breeders dedicated to their training and diet, feeding them meat, eggs and vegetable peelings.

"Cockfighting brings people together across all regions and social classes," 42-year-old Safa Abu Hassan said.

"Whether they are officers, businessmen, or civil servants, there is an atmosphere of enthusiasm here that is comparable to any sporting event," he added, noting that though he has been watching cockfights for more than 20 years, he only rarely puts down a wager.

He recalled one cockfight in 1993, "the most enthusiastic I have ever seen, between two roosters belonging to senior government officials in Baghdad".

"The total bets added up to around $1,500."

On this particular day, Daqduqa and Sammam competed tirelessly in the ring, jumping in the air and creating a flurry of feathers as the crowd roared them on.

After the bell rang for the scheduled two-minute break, their breeders took them back, poured water on the roosters' wounds, gave them a drink and massaged their legs.

A bookmaker solicited bets from newly arrived spectators, with wagers ranging from $3 to $100.

Ali Salim, Sammam's owner, sat in a corner, chain-smoking cigarettes as he watched the fight while his rival was perched on the opposite side of the ring, hitting his thigh whenever Daqduqa suffered a major blow.

Eventually, Daqduqa collapsed for a third consecutive round and Sammam was declared the winner.

Through it all, little notice is given to animal rights or concerns over cruelty towards the birds.

"The greatest rooster I had was one called Qardash, who won seven matches in a row in 2009," said Mahmud, a breeder for more than 20 years, who currently owns 17 roosters.

"But the cocks do eventually die, and, of course, this saddens me," he added. "But ultimately, this is a sport. In every sport, there is a winner and a loser."

Agence France-Presse

Relief reaches isolated village

Relief reaches isolated village

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Earth Day marked around the world

Earth Day marked around the world

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|