A sherry time had by all

Updated: 2013-10-13 08:28

By Geoffrey Gray (China Daily)

|

||||||||

The genie that is palo cortado is unbottled in a visit to three bodegas in Spain. Geoffrey Gray investigates.

Among high-end sherries, palo cortado is a mystery. A century ago, perhaps longer, tasters would check on the casks to ensure that the sherry inside fell into its proper category. Was it the lighter manzanilla or fino? The drier amontillado? Or the darker oloroso?

Occasionally, sherry noses stumbled on a wine that was none of the above. Unable to classify it, the tasters marked the barrel with two slashes of chalk. This palo cortado ("cut stick") meant the barrel could not be sold, and the wine inside was often tossed.

What a pity, many sherry-makers thought. That a sherry could not be defined did not make it a bad sherry. So many bodega owners decided to keep a few barrels around for limited sales or for personal use. The sherry was appealing in its enigmatic way. It refused to be defined with its own rebellious spirit, much like the sherry-makers themselves.

Their bodegas are concentrated in a region called the Sherry Triangle, demarcated by three cities in southern Spain. The tradition for many there is to drink as many as eight glasses of sherry a day, starting at noon, often earlier.

Locals go to the bodegas with plastic jugs and have them filled with the lighter and younger manzanilla or fino for only a few euros. In contrast, palo cortado is hard to find and can retail for upward of 40 euros per bottle ($52) and higher, a price point that is out of reach for daily sherry drinkers.

There are bodegas that serve it, though, or will plunge their tasting canes into their private barrels to indulge the curious and thirsty. While many palo cortados out there are merely different sherries mixed together, and aren't considered pure by aficionados, some bodegas have been in the business of making the real thing for more than a century. Below are three who opened their doors to a visitor.

Bodega Gutierrez Colosia

The space felt like a dark cathedral, cool and damp, and hanging lanterns glowed against the old arches and the faces of the big oak barrels.

Resting his tasting cane over his shoulder like a hunting rifle, Juan Carlos Gutierrez walked to the back, through a door, and into a chamber where he kept his oldest, most prized creations. He removed the cap from one barrel, plunged the cane into the liquid and began the intricate pour: A flick of the cane up fast, letting the amber-colored sherry drip from the flute at the bottom of the cane like a rainbow. It fell in a perfect stream, and landed several feet later into the pit of a glass.

"I cannot tell you how to make this wine," he says, handing the glass to me. It was a surprising statement, considering that Gutierrez has been making sherry wine all his life in El Puerto de Santa Maria, one of the three points on the Sherry Triangle.

What he meant, of course, was that he couldn't explain that specific sherry. But he insisted on giving me an overview of the process before I had a sip. Think of making sherry as the opposite of making other types of wine, he told me.

In traditional winemaking, for instance, the vintner is mainly dependent on the natural world for the quality of the wine. The terroir of the grapes, what the weather was like the year that they grew there and how well they aged. With sherry, none of these factors matter. The only grape that sherry-makers here use and that grows well in the dusty, sun-baked soil of Andalusia is the palomino, a small, lightly colored variety. Vintages are also irrelevant since the sherry process doesn't rely on a particular year. It relies on all of them.

Tasting his own palo cortado, Gutierrez had no idea how old the original batch was. It could be 50 years old. Could be older.

Avenida Bajamr, 40. El Puerto de Santa Maria, Cadiz. For visiting hours, seegutierrez-colosia.com.

Bodega Obregon

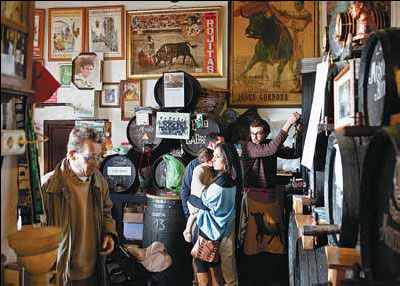

"Here is our palo cortado," Alvaro Obregon says, pointing to the barrel in the corner of the bar and bodega his family has run in El Puerto de Santa Maria for four generations. Bodega Obregon is the rare bar in Andalusia where there is no bar. It is simply a tall room, lined with bullfighting posters and filled with barrels. A few seats are interspersed, like the break area of a warehouse, and Obregon and his brother and his father walk the room with plastic funnels to direct the bodega taps into glasses.

"My grandfather thought it was not very personal," Obregon says about the decision not to have an actual bar for resting a drink or an elbow. For a sip, he retreated to the back room, where pictures of his family hung amid the old barrels.

Unlike other sherries they offer, his family's palo cortado is not advertised. If you want a glass, they won't turn you down. But good luck trying to pay for it. Here, the palo cortado is treated like a tradition, one that the family has kept alive for generations. So it's also pride that they are serving, and pride that they want to share, not profit from. It's best to enjoy with friends, and paired with an aged cheese.

Zarza, 51; El Puerto de Santa Maria, Cadiz; 34-95-685-6329.

Hidalgo-La Gitana

In the Sherry Triangle, the bodegas that benefit most from the moist river and salty ocean air are in Sanlucar de Barrameda, a vacation town also known for its prawns and summer horse races on the beach.

One big producer here is Hidalgo-La Gitana, which dates its sherry-making to 1792. The bodega is a sprawling compound in the center of the city, and its owner, Javier Hidalgo, a slight, elegant man with slicked-back hair, walked me through the endless rows of his family's sherry barrels, across a patio of caged doves and dripping bougainvillea, and down some stairs to a building that had the feel of an underground bunker.

Inside the bunker, he flicked on a fluorescent light and found the palo cortado. "This wine is not an accident," he said. "We very much make this wine, and it takes generations of a family to make this wine."

He plunged his tasting cane in, and poured a sherry rainbow into some glasses. He sniffed, swirled. He tossed the wine around the glass so hard to get the top notes popping that it splashed over his hands, his pants, onto the floor.

"Iodine, shellfish," he said, inhaling into the glass and dissecting the nose.

"Mahogany, old furniture," he went on, and we both took a sip and waited for the mystery of the palo cortado to kick in. He said: "It has the finesse of an amontillado. The structure of an oloroso. The freshness of a manzanilla."

In the bunker, Hidalgo lamented the inefficiency of the cortado. He has now devoted 23 barrels to making it, each slowly aging, then mixing into the next. It was all wasted space in a way, considering he sells only 800 bottles a year, for charity.

Calle de la Banda de la Playa, 42; Sanlucar de Barrameda, Cadiz; lagitana.es.

The New York Times

|

In Bodega Obregon, the owner fills a bottle of sherry for a customer. Provided to China Daily |

(China Daily 10/13/2013 page16)

Victoria Beckham S/S 2014 presented during NYFW

Victoria Beckham S/S 2014 presented during NYFW

'Despicable' minions upset Depp's 'Lone Ranger' at box office

'Despicable' minions upset Depp's 'Lone Ranger' at box office

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

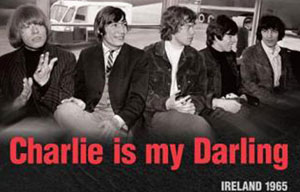

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Going green can make good money sense

Senate leader 'confident' fiscal crisis can be averted

China's Sept CPI rose 3.1%

No new findings over Arafat's death: official

Detained US citizen dies in Egypt

Investment week kicks off in Dallas

Chinese firm joins UK airport enterprise

Trending news across China

US Weekly

|

|