Bleat of the hybrid ushers in new era

Updated: 2013-11-07 10:42

By Sun Yuanqing (China Daily)

|

||||||||

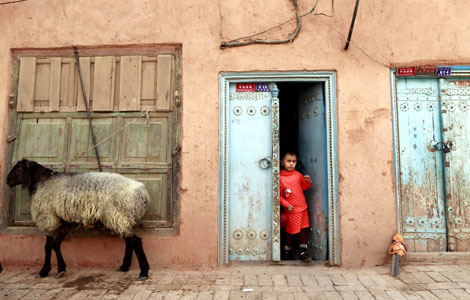

Transfer technology is producing a type of sheep that flourishes in the harsh conditions of Qinglong county, Guizhou province, while lifting many local farmers out of poverty. Sun Yuanqing reports.

Fan Shunhua's day is a successful one when he hears the bleating of newborn lambs. Fan has experienced the happy sound more than 140 times this year and expects 60 more such occasions by year-end. With 400 Qinglong sheep in the sheepfolds, Fan rarely has a moment's rest. He goes out in the morning to collect grass, feeds the sheep several times a day and checks their health before going to bed.

"It is not easy to raise 400 sheep, but it's going very steadily. I actually regret not starting it earlier," Fan says.

Previously a mason with no stable income in Qinglong county in the southwestern province of Guizhou, Fan started raising sheep in 2011 along with many townsmen.

Qinglong sheep, a hybrid of local and foreign sheep, have become a way out for Qinglong county, a typical karst area plagued by rocky desertification and poverty.

"Australian White sheep are good in Australia, but not necessarily so in Qinglong. What we are doing right now is breeding a kind of sheep that can survive in Qinglong as well as the Australian White does in its own local environment," says Zhang Daquan, director of the Qinglong County Grassland Center, a government body that has been promoting animal husbandry on Qinglong's grassland.

What Zhang and his team have managed to breed is a kind of sheep that has the best of two worlds: the adaptability of the local livestock and the productivity of the world's best sheep for meat, including Australian White and Dorper sheep and Boer goats.

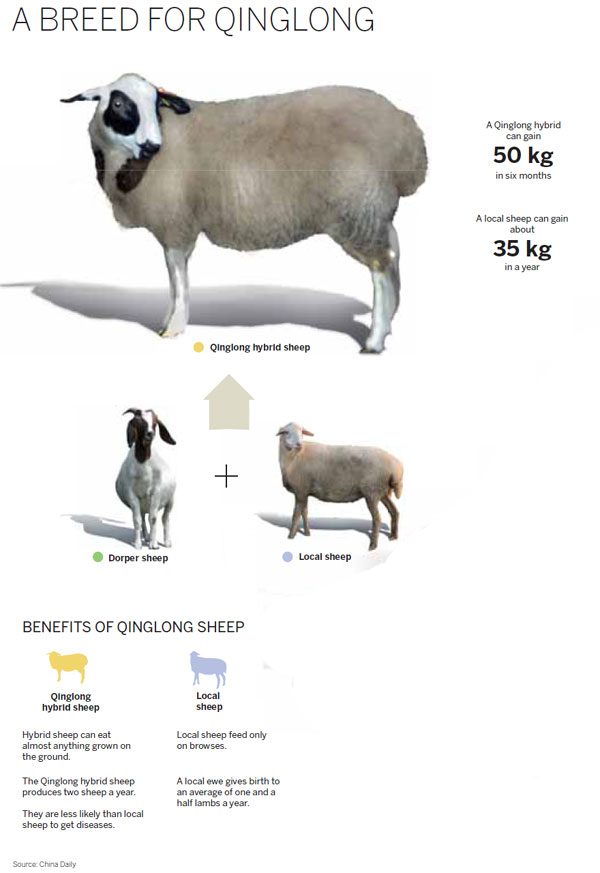

A local sheep gains about 35 kg a year, but a Qinglong hybrid can gain 50 kg in half a year. And the quality of meat is better. The local sheep feed only on browses, while the hybrid ones can eat almost anything grown on the ground.

"They are not only more adaptable than both the local and foreign breeds, but also more productive," Zhang says.

A local ewe gives birth to an average of one-and-a-half lambs a year, while the Qing-long hybrid sheep produces two sheep in the same period of time. Moreover, they are less likely to get diseases.

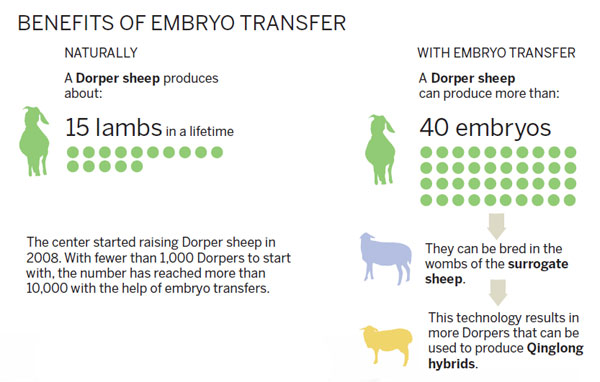

Instead of importing the foreign sheep that cost from 18,000 yuan ($2,960) to 25,000 yuan a head, which is unaffordable for the local farmers, the center applies a more economical and efficient method - embryo transfers.

The center cooperates with Australian and New Zealand breeding companies that provide embryos and transfer technology to implant the embryos in the wombs of the local sheep. Naturally a sheep produces about 15 lambs in a lifetime. With an embryo transfer, a sheep can produce more than 40 embryos that can be bred in the wombs of the surrogate sheep.

Peter Lynch, manager at Animal Breeding Services in New Zealand, says Qinglong is ready for embryo transfer technology given the current management level.

"Good management is the key. There is no point bringing technology if you cannot feed the animals properly," Lynch says as he prepares for a six-day embryo transfer operation in Qinglong. "To bring the technology, you have to have the management and nutrition and animal health properly in place. What they are doing in Qinglong is quite impressive."

The center started raising Dorper sheep in 2008. With fewer than 1,000 Dorpers to start with, the number has reached more than 10,000 with the help of embryo transfers. It is expected to excel 20,000 by the end of this year, Zhang says.

However, breeding the right kind of sheep is only the beginning of the Qinglong model, which is lifting tens of thousands of local farmers like Fan out of poverty.

The center not only loans sheep to the local farmers, but also provides training and subsidies.

The center, which loaned Fan more than 400 Qinglong sheep, also gives subsidies for sheepfolds, free sheep medicine and grass-processing machines. Every two or three months, Fan has a training session on sheep herding. Technicians come on a regular basis to check if he is raising the sheep the right way.

Last year, Fan's sheep produced about 200 lambs, and he says he should be able to return the "sheep loan" by the end of this year.

An average Qinglong sheep sells for 2,000 yuan a head, compared with 800 yuan in 2007.

"The biggest challenge for China is the supply chain from the farmers who are growing the meat to where it goes into the supermarket," says John Owens, director at Future Livestock from Australia, who is working with Lynch in Qinglong. "When people shop in the supermarkets in Beijing and Shanghai, they want to guarantee quality."

Farmers in Qinglong worry little about marketing. They can sell by themselves, or, if the market price is too low, they can ask the center to sell for them. The center guarantees a minimum price of 36 yuan a kg to ensure the benefits go to the farmers.

More than 12,800 local households are now taking on sheep farming and 90 percent of them are operating independently like Fan.

While operating on their own, they are in a way all contributing to breeding Qinglong sheep and practicing the Qinglong model, which is likely to benefit more people in the future, Zhang says.

"The strain of Qinglong sheep is already there, but it will still take five years to stabilize and build the numbers up. And once it's steady, we will promote it in the whole area of West China," Zhang says.

Zhang was the first person to promote large-scale sheep raising in Qinglong in 1988 after witnessing how shepherds from neighboring Yunnan province prospered by raising sheep on the grassland in Guizhou.

The breeding of Qinglong sheep has not only dragged Qinglong out of poverty, but also recovered a majority of its rocky and desertified karst land.

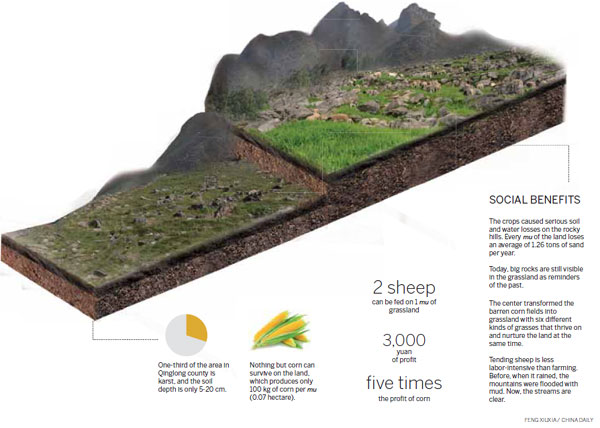

One-third of the area in Qinglong county is karst, and the soil depth is only 5-20 cm. Nothing but corn can survive on the land, which produces only 100 kg per mu (0.07 hectare).

Moreover, the crops caused serious soil and water losses on the rocky hills. Every mu of the land loses an average of 1.26 tons of sand per year. Today, big rocks are still visible in the grassland as reminders of the past.

The center transformed the barren cornfields into grassland with six different kinds of grasses that thrive on and nurture the land at the same time.

"As grassland, 1 mu of land could feed two sheep, which can return 3,000 yuan of profit - five times that of corn. Sheep raising is also less labor-intensive than farming," Zhang says. "Before, when it rained, the mountains were flooded with mud. Now, the streams are clear."

Contact the writer at sunyuanqing@chinadaily.com.cn.

Zhao Kai contributed to this story.

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

World to see boom in big firms

U. Michigan gets grant for China center

Lead author of Obamacare law blames govt for rollout

China's increasing role in global nuclear power

US companies in China feel squeeze

Panda cub drawing votes for her name

US, China team up for wildlife

E China still top draw for foreigners

US Weekly

|

|