The 'house-as-an-ATM' experiment

Updated: 2014-08-22 11:03

By Chris Davis(China Daily USA)

|

||||||||

China has given four cities approval to offer what some will have nothing to do with, while others may find it an answer to living comfortably as they age - the reverse mortgage. The financial instrument that taps into a home's value has supporters and detractors in both the United States, where it has existed for more than 25 years, and China, reports CHRIS DAVIS from New York.

It is an ages-honored tradition, a tradition that has been lifting many Chinese families out of poverty.

Now, some see a direct threat to that tradition in a two-year experiment that the city governments of Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and Wuhan have been given the go-ahead to start, and if the experiment is successful, officials say it will be rolled out nationwide. It is the reverse mortgage, or what some call the "house-for-pension scheme".

|

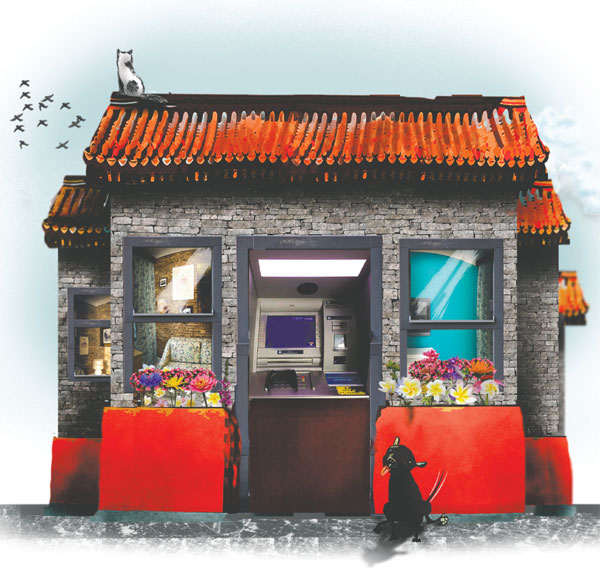

Without selling a house outright, a reverse mortgage allows a home owner to draw on the value of the property bit by bit as needed, turning a home, for all intents and purposes, into a cash machine. The tool has worked well in the US for the last quarter century and now China has given the green light for a house-for-pension pilot it to be tested in four major cities. Guillermo Munro / China Daily |

And the push for it comes down to numbers: An aging population that is income-poor and house-rich, and the need to ease the pressure they put on a society's resources by unlocking a home's value, bit by bit, without selling it outright.

At the end of 2013, the Chinese population aged 60 was 202 million, or 15 percent of the total.

Even though China's social security fund stood at 1.1 trillion yuan ($179 billion) - up from 838.6 billion yuan in 2011 - the pension-financing gap will hit 68.2 trillion yuan by 2033, up from 16.5 trillion yuan in 2010, according to Cao Yuanzheng, chief economist at the Bank of China.

When the China Insurance Regulatory Commission announced the pilot program for reverse mortgages in June, it said, "The scheme provides a new way for old-age care."

"For old people who don't have children, have property but lack cash, we offer them a choice to turn their fixed assets into current assets, to live more comfortably in their own home in their old age," said Yao Yu of the commission.

The same "offer" has been in existence in the United States for more than 25 years, and it has its supporters and detractors, some of whom see potential problems for it in China.

Yael Ishakis, a loan officer and vice-president of First Meridian Mortgage in Brooklyn, New York, said that one of the reasons reverse mortgages have been so successful in the US is because the values of homes usually appreciate and it's a win-win for all involved.

"Because it's a government backed program there is no bank taking a loss when a foreclosure occurs," Ishakis said in an email interview with China Daily. "However I'm not confident the Chinese government is set up for: 1. Expected losses should a senior live a longer age or the house depreciates; or 2. Can the heirs actually refinance upon the death of the parent? Are there mortgage programs set up not to have the family or ancestral home get foreclosed upon because the balance of the loan became too exorbitant for the heirs to take on?"

The pilot program, according to Sang Yufeng, a marketing director in Beijing for the real estate brokerage firm Century 21, a franchise of IFM Investments Ltd, will help stimulate the pre-owned home market.

"These properties will be important mortgage assets for insurance companies and can later be used in asset securitization," Sang told China Daily.

An act of kindness

The first reverse mortgage in the US was written in 1961 out of kindness by a private savings and loan officer named Nelson Haynes at a small bank in Portland, Maine. He wrote it for Nellie Young, the widow of his high school football coach, who was having trouble making ends meet. The aim was simple - to allow Young to stay in her home after losing her husband by gradually drawing down on the value of the house.

Eight years later the concept of tapping into a house's equity got a boost at a hearing before the Senate Committee on Aging when economist and gerontologist with University of California, Los Angeles Yung-Ping Chen - who was born in Jingjiang, Jiangsu province in 1930 - testified: "I think an actuarial mortgage plan in the form of a housing annuity can serve two purposes: First, to enable older homeowners to realize the fruits of savings in the form of home equity; and second, to enable those homeowners who wish to remain in their homes either for physical convenience or for sentimental attachment, to do as they wish."

Soon the idea began to take hold among economists, academics and banks.

For years Chen had been researching the very issues that China is grappling with now: an aging population that is "income-poor and house-rich" and how to ease the pressure they put on a society's resources by unlocking a home's value, bit by bit, without selling it outright.

The idea continued to catch on through the 1970s as more and more academics analyzed its feasibility.

In 1987 Congress authorized a reverse mortgage -now called Home Equity Conversion Mortgage (HECM) - pilot program, and in 1988 President Ronald Reagan signed into law the Housing and Community Development Act that proposed federal insurance for reverse mortgages.

To date, more than 860,000 HECMs have been written in the US, including 60,091 in the most recent federal fiscal year, ending Sept 30, 2013, according to the National Reverse Mortgage Lenders Association (NRMLA).

NRMLA says the uptick in "popularity" of reverse mortgages is probably the result of two factors: as people learn more about the tool they are more comfortable with it; but, more importantly, belt-tightening caused by higher healthcare costs and lower returns on investments.

Today, more than 34 million Americans are 65 or older and that number is expected to more than double over the next 30 years to 70 million, NRMLA says. Almost four out of five seniors own their own homes, or 27 million senior homeowners in the US.

That amounts to a tremendous amount of equity. And at the same time seniors have the lowest median income of any demographic group. Also, as seniors age, their incomes do not generally increase, but their needs do. Homes need maintenance, chronic illnesses require expensive care and medications, old people increasingly need help.

Since then the rules of the game in the US have continued to change and modify to the point where the clich governing reverse mortgages is "change is the only constant". Most modifications seem to be aimed at making them safer for borrowers and insulating them against predatory practices.

Studies by the American Association of Retired People (AARP) have shown that seniors will sacrifice considerable quality of life in order to remain in their homes for as long as possible. AARP surveys have found that 65 percent of senior homeowners plan to stay in their homes as long as possible and 82 percent of senior homeowners who require some level of assisted living prefer to remain in their own home as long as possible.

Reverse mortgages allow this to happen. "Seniors do not have to repay the loans until they die," the NRMLA website says. "They can never owe the lender more than the home is worth when the loan is due."

In the US reverse mortgage system, the home-owner can usually receive the cash in a lump sum, a regular monthly advance, a "line of credit" to be drawn on at will or any combination of the three. However the cash is taken, the loan does not have to be repaid until the owner permanently moves out of the house, sells it or dies.

Not for everyone

The drawback, of course, is that the amount a homeowner owes gets bigger every month, so the financial tool is not wise for everyone. "If you want to take a dream vacation, a reverse mortgage is a very expensive way to pay for it," AARP advises on its website. "Investing the money from these loans is an especially bad idea, because the loan is highly likely to cost more than you could safely earn."

Robert DeLeonardis, a principal at Fenwick Keats Real Estate, a residential property and management firm in New York City, said reverse mortgages make sense for some. "People who are cash poor and have equity in a home," he said. "If you have a difficult time making your payments and you're getting on in years and you want to tap some of the equity in your home."

DeLeonardis said he and his brother orchestrated a reverse mortgage for their mother and got first-hand experience with the process.

The two most obvious immediate advantages, he said, were his mother had instant money in her purse and she didn't have to make monthly payments any more.

"The disadvantages are that your mortgage goes up every month," he said. "You don't make the payment but it doesn't mean that the mortgage stays still. So that has a negative impact on your inheritance. So your kids will get less money."

The two key factors lenders measure by are the owner's age and the house's loan-to-value ratio, that is, how much is already owed on the house compared to its market value.

"Let's say your home is currently worth $500,000 and you currently have a mortgage of say 90 percent, somewhere in the mid $400,000s. You're likely not eligible, depending on your age," DeLeonardis said.

But suppose that $500,000 home had only a $100,000 mortgage and the owner is of a certain age. Lenders run the actuarial tables and see it's a safe bet that when it comes time to sell, there will be enough equity left that the bank will be made whole.

The guidelines change, however. "My mother has defied the actuarial tables," DeLeonardis said. "If she went to get a reverse mortgage today, she wouldn't be eligible." Despite her added years, the loan-to-value ratio had accrued beyond the limit.

DeLeonardis learned another lesson by managing the deal himself. He originally got a reverse mortgage through MetLife, but that was six years ago. Since then, MetLife has gotten out of the reverse mortgage business. They sold his mortgage to someone else, who in turn sold it again.

"My mom's loan has been sold three times," he said, adding that he got into a big argument with the current holder, who had sent a declaration of primary residence form to his mother, who is 81, and because she had failed to notice it, much less fill it out or send it in, they were going to consider the loan in default.

"It was kind of squirrely that they would do something like that to an 81-year-old woman," he said. "That's not very nice. It prompted a call from me to them and I'm sure that they've gotten other complaints."

Still, DeLeonardis warned, owners have to be conscious that the loan could be sold and sometimes onerous restrictions and requirements can be added on. "You've got to stay on your toes and be diligent," he said.

Whether the house-for-pension program will work in China has experts concerned for a variety of reasons. Home ownership in China is capped at age 70 and for countless generations, homes have been passed along to next generations as a major inheritance.

"The house is generally believed to be the dearest gift to offspring and many elders prefer to spend the rest of their life in their own home," Wen Jun, a sociologist at East China Normal University told Xinhua.

Li Qimin, a 65-year-old retired teacher in eastern China's Zhejiang province, told China Daily that the reverse mortgage is an unacceptable practice for her. "I could live a decent life with my pension. And I would definitely leave my apartment to my daughter," said Li.

David Reischer of legaladvice.com said that a loan-to-value ratio of 65 percent works well when property values are rising because the chances are small that the lender will end up with a house that is worth less than the size of the mortgage. Recently, however, property values have declined substantially and borrowers are living longer than previous generations (and the predictions of the actuaries).

"In China," Reischer wrote in an email interview with China Daily, "this type of arrangement may be even more risky if the property is in a bubble right now, like many people suspect China is in. The Chinese taxpayers will be on the hook for eating any losses for mortgages underwritten to subsidize the older generation. Young Chinese taxpayers will be forced to pay higher taxes to eat bank losses that result from these reverse mortgage loans."

Guan Jiaoyang, general manager of Wuhan-based Union Life Insurance Co Ltd, said there are two major clients for reverse mortgages - those with significant assets and those who have no immediate relatives. As a new product, the major challenges include the valuation of properties, the levy of property tax and the tradition of parents leaving their property to their children, Guan told China Daily.

Not a sure bet

Some analysts call the Chinese house-for-pension project a niche product fit only for childless urban seniors to improve their lifestyles. Unlike in the big cities where housing is exorbitantly priced, village huts in China's vast rural areas go cheap and aren't a sure re-sale bet for insurance companies and banks.

Xinhua spoke with Yin Shoutang, 71, who lives with his wife, his 91-year-old mother and a granddaughter in a suburb of Wuhan on a monthly pension of 2,200 yuan ($357), which compels him to work part-time as a carpenter.

Yin considered taking a second mortgage on his 110-sq-meter house, but the problem is his house is only worth about $32,520. "We may spend all the loan and die homeless," he said.

One elderly gentleman interviewed on the issue by The Workers' Daily said simply: "It is not I alone who can make a decision on the property. What would my children think?"

An editorial in The Guangzhou Daily cautioned that toying with an ages-honored tradition of passing homes down to younger generations - a tradition that has been lifting so many families out of poverty for so long - could backfire. "A reverse mortgage may only lead to family disputes," it said.

"The house is my most precious asset and legacy, and after I die, I must give it to someone I know and trust," Xia Wuyi, 70, an unwed, childless man in Shanghai told Xinhua. Xia, who suffers from Alzheimer's Disease, had cut his own deal to leverage the value of his house, improvised out of compassion and practicality - the same way the original reverse mortgage came about way back in Maine in 1961.

Xia adopted a local peddler girl as his daughter and promised to leave her the property if she stuck to her promise to take care of him through his twilight years.

Contact the writer at chrisdavis@chinadailyusa.com

Hu Yuanyuan in Beijing contributed to this story.

(China Daily USA 08/22/2014 page20)

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Lawmakers in move to tackle espionage threat

Airplanes' skirmish still debated

Mugabe a frequent visitor to China

Australian MP apologizes for insulting Chinese

US hypersonic weapon destroyed seconds after launch

Cathay Pacific to launch new Hong Kong, Boston route

Duke Kunshan welcomes its first class in China

Consulate pioneers Facebook-diplomacy

US Weekly

|

|