Son of the Red River

Updated: 2012-06-11 10:16

By Cang Lide (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

|

Lu Chaogui: He has spent the past 20 years of his life documenting and translating Hani literature. Photos by Li Jincan / for China Daily |

|

|

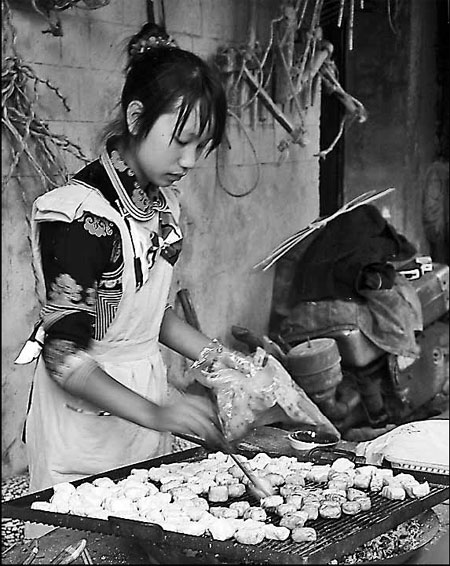

A Hani girl works a grill preparing beancurd. |

Farmer-scholar Lu Chaogui has dedicated his life documenting and preserving Hani culture. Cang Lide visits him at home in the Yuanyang rice terraces.

His reputation goes before him, and even before we meet, we are told that he is a respected scholar of Hani culture, and that visitors and researchers from home and abroad often go to great lengths to seek an audience.

When we meet him, he has no airs at all, but welcomes us warmly into his courtyard home in Quanfu Village, where the Hani way of living has been preserved to this day.

Lu Chaogui, in his early sixties, obviously holds a high and respected position in the village. Also gathered to meet us are the village chief and various agriculture board officials. Even the local police chief has joined us for lunch.

Standing in his courtyard, Lu greets us with a smile lighting up his tanned but taut complexion. He is well-preserved for his age, with large sparkling eyes and brows with no hint of white, a handsome specimen of a Hani male.

He wears the traditional head cloths of the Hani and a blue vest lined with embroidery over a set of pristine whites.

His home is a courtyard surrounded by a two-storied building on three sides.

There is a tree shading the compound, under which a yellow-beaked mynah chirrups softly. The bird was rescued from a nearby hilltop after it fell out of its nest a year ago.

"We have a little more than 5 mu (one third of a hectare) of rice terraces which can produce about 500 kilograms of rice each year. That's more than enough for my wife and me," he says.

"Rice is the lifeblood of our Hani culture," he says.

After graduating from the local high school, he went on to study at the Minzu University of China in Beijing, majoring in classical archives. Later, he returned home and became a government employee in Yuanyang county, Honghe prefecture.

He followed the call of his ancestors, quit his job some 20 years ago and returned to his beloved home village.

This was the turning point of his life. Since then, he has spent all his time devoted to the research and promotion of the Hani culture.

He has 4 million words of published works as proof of his hard work, but it did not come easily.

The Hani have no written system, and he had to spend much time collecting various Hani folklores and songs, and translating them into Han Chinese.

Among his works are Hani Ethnic Stories, Hani Fore-fathers Crossing the River and Eulogy for Mother, all of which describe how the Hani settlers carved out and developed a whole culture and lifestyle on the rice terraces.

Lu's Hani penname is Lang San Ran, which means "son of Honghe, the Red River."

Lunchtime, and we are invited to eat at a low table set up in the yard piled high with dishes cooked by Lu's wife. It was a bountiful display of the self-sufficient Hani lifestyle.

Everything on the table was either from his paddy fields or from the nearby hills, all organic and home made. Red rice, salted pork, chicken, lightly brined duck eggs, paddy field fishes, loaches, water celery, orchid shoots, yams, toon tree leaves

Lu proudly tells us there are more than 20 edible aquatic animals or plants in the rice fields and you can always find something to eat, all year round.

It reminds me of a poem that describes the rich, natural Hani cuisine:

"Hundreds of flowers are in the dishes,

Hundreds of insects are so delicious,

Hundreds of herbs are on the dining table,

Hundreds of leaves make a banquet."

After lunch, Lu took us on a tour of the village. Along the narrow cobbled lanes, black pigs lazed by the side. Chickens led their broods scratching along the lanes and ducklings were swimming in the clear ditches, stopping occasionally to peck at herbs growing along the edges.

"This is the water dividing stone set up by the first settlers of our Lu clan," Lu points at a stream where a block of stone with two deep grooves diverted the water into two ditches.

"Our family tree can be traced back 45 generations, for well over a thousand years," he says. "Rules and regulations by our ancestors regarding water distribution have been obeyed faithfully. This is vital for the sustainability of our rice terrace."

In front of a thanksgiving shrine, where an annual ceremony is held to pay respect to the gods of rice, Lu tells us proudly that each living creature is precious to the well-being of Hani livelihood.

As we struggle up the hilltop, he learns that one of us has an arthritic knee, and he immediately picks up a fleshy herb.

"See, this is called morning dew grass. You stew it together with a 10-year-old goose, drink the soup and eat the meat. Then, you grind up the bones, and you eat that too. It's sure to cure the knee."

When we reach the top, we pause for a panoramic view of the village and its surrounding tiers of wet terraces glittering in the sunshine, and I think to myself: Having such staunch guardians like Lu, the wisdom of the Hani people will be preserved for generations to come.

Contact the writer at canglide@chinadaily.com.cn.

- African culture to be promoted in China

- China to showcase cultural heritage at biggest U.S. folklife festival

- Five Characteristics of Guangxi Ethnic Culture

- Mongolian culture courses taught in Hohhot

- Morsels of culture

- Book deal opens new chapter in nation's cultural exchange

- Booming cultural presence

- London Book Fair places Chinese culture in the spotlight

- Centers of culture

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|