Where Victor Hugo found freedom

Updated: 2012-08-12 07:55

By Ann Mah (The New York Times)

|

||||||||

|

|

In October 1855, Victor Hugo arrived on rainy, wind-swept Guernsey to seek refuge.

A fierce opponent of the Second Empire of Napoleon III, he had been banished first from his native France, and then Belgium and the island of Jersey.

By the time he landed on this small neighboring island in the English Channel, the exiled writer was in desperate need of asylum.

He found it on Guernsey.

The "rock of hospitality and freedom", as Hugo proclaimed it in his seafaring novel Toilers of the Sea set on the island, would become his home for over 15 years.

Undistracted and determined, he poured his creative energy into masterpieces like his epic novel Les Miserables and the decoration of his home, Hauteville House, the only home he ever owned.

"Exile has not only detached me from France, it has almost detached me from the Earth," he wrote in a letter.

In this wild, isolated retreat, a British dependency just 26 miles from the Normandy coast of France, Hugo passed the most productive period of his life.

From the minute his boat docked at St. Peter Port, the capital of the 24-square-mile island, Hugo marveled at the beauty. "Even in the rain and mist, the arrival at Guernsey is splendid," he wrote in a letter to his wife.

Today, travelers who arrive by ferry, from either England, Jersey or France, share this same first glimpse of the port, with its gently bobbing fishing boats and orderly rows of houses stacked along hills.

Hugo settled in one of these residences at the top of town, a rambling villa called Hauteville House, surrounded by family and a band of fellow exiles. He installed Juliette Drouet, his mistress of decades, in a modest home down the street.

Already a celebrated writer at the time of his exile, Hugo was drawn to the Channel Islands because of their proximity to France and independent governance. (Though the islands have been linked to Britain for almost 1,000 years, a 1204 charter still guarantees their autonomy.)

For Hugo, who spoke no English - "When England wants to chat with me, let her learn my language," he said with typical grandiosity - the French and Guernsey patois spoken by the island's Norman descendants were essential to his comfort.

Today, locals speak English more than any other language, but the warmth of their hospitality remains undimmed.

"It's such a small island, everyone knows everyone - in a nice way," says Mark Pontin, the proprietor of Ship and Crown, a local pub where Juliette Drouet first stayed when she arrived on Guernsey.

"Most locals know the stories about Victor Hugo, and people have plenty of time to talk about the history of the island."

In his mid-50s when he arrived in Guernsey, Hugo believed that his "present refuge" would eventually become his "probable tomb."

Fueled by these morbid fears - amplified, no doubt, by his remote isolation - he embarked on a staggeringly prolific literary output, as well as his most tangible work of art, the decoration of his home, Hauteville House.

In 1927, Hugo's granddaughter, Jeanne, and great-grandchildren, Jean, Marguerite and Francois, donated the property to the city of Paris, which maintains it as a museum, open from April to September.

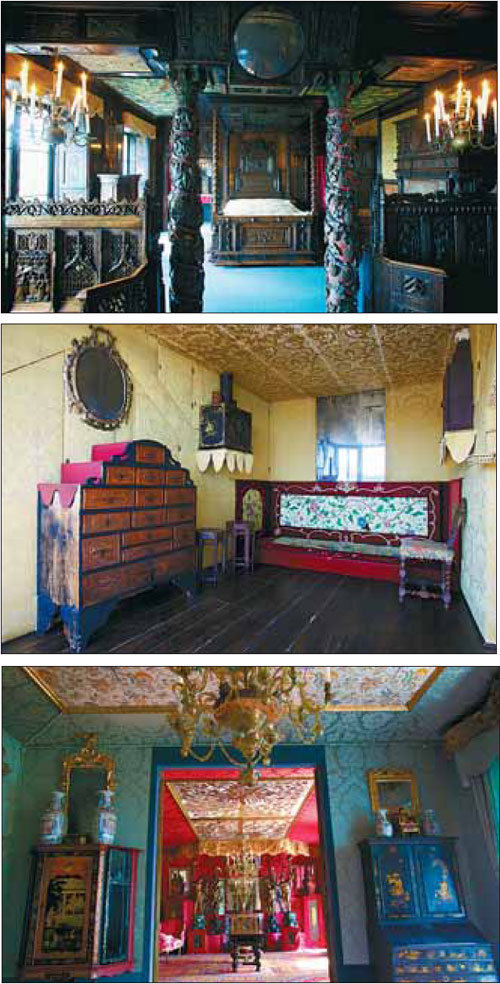

Stepping into the house, which brims with objets d'art and swaths of tapestry, is like entering Hugo's imagination, filled with hidden symbolism, defiant declarations and winks of humor.

"The house is like a journey," says Cedric Bail, a conservation assistant.

Hugo spent almost six years decorating the house, scouring the island's junk shops for functional items that he repurposed into decorative elements. Under his keen eye, dozens of carved wooden sea chests were joined into a towering mantelpiece, and curved Regency chair backs became ornamental window frames. Small faces and words - "bits of propaganda," Bail said - are carved into the wall paneling: A sign over the dining room door reads, "Exilium vita est" ("Life is an exile").

Suffused with a dark oppressiveness that Bail likened to that of a prison, the lower rooms gave way to light as we ascended the stairs. At the top of the house, a glass conservatory, shockingly bright, housed Hugo's primary domain: a spartan bedroom - where the notorious philanderer slept flanked by maidservants' beds - and an office with views that stretch across the Channel.

Perched here in the "lookout," as he called it, Hugo wrote while standing at a foldout desk and gazing at the islands of Sark and Herm, and, in the hazy distance, his beloved France.

After mornings of work, Hugo spent his afternoons on brisk walks exploring the island. His hale figure was such a familiar sight that a statue in a nearby park, Candie Gardens, depicts him midstride, the wind catching his cloak.

I toured some of Hugo's haunts with Gill Girard, a guide (and the sister of Pontin, the pub owner), who shared rich local tales while whisking me around in her car.

She stopped to show me the Creux es Faies ("cave of fairies" in Guernsey French), a Neolithic-era burial chamber that fascinated Hugo.

At Pleinmont Point, on the southwestern corner of the island, our eyes strained through the fog to see a lonely house that might have inspired a scene in his "Toilers of the Sea".

Today, massive cement bunkers mar the view - built during World War II, they are an unyielding reminder of the German occupation - but the craggy lines of Hugo's beloved "ravaged, exposed" coast remain.

On my final afternoon, a fine rain dampened the skies. Undeterred, I set off to retrace Hugo's favorite walk, a one-hour hike south from St. Peter Port along coastal cliffs. Dark woods closed in above me, and the occasional drop of icy rain fell on my neck, but as I scrambled along the path, all distractions were swept away by the roar of the sea, which filled my ears even though I couldn't see it.

I rounded a corner, and Fermain Bay appeared below, the jewel-toned waters glowing through the mist. Hugo came to this sheltered cove, which is still accessible only by foot, to swim and sit and watch the rising tide. Surrounded by his thoughts, he found a kind of peace.

Hugo was prepared to die without setting foot again in France, declaring, "I will share exile and liberty to the very end." In 1870, however, the Second Empire fell, and a triumphant Hugo returned to Paris, though he visited Guernsey again three times before his death in 1885.

And yet Guernsey's influence on Hugo is evident not just in Toilers of the Sea but in the sheer volume of the work he produced there. The island's untamed seclusion was at once a burden and a gift, and the ambitious writer freely embraced both aspects. "A month's work here is worth a year in Paris," he confided in a letter to the writer Auguste Vacquerie. "This is why I sentence myself to exile."

|

|

The New York Times

If You Go

Getting there and getting around

Guernsey can be reached by daily ferry service operated by Condor Ferries (www.condorferries.co.uk). The trip takes about three hours from Weymouth or Poole on the southern English coast (60 pounds, about $95 at $1.58 to the pound, round trip), or two hours from St. Malo, France (65 euros, $84 at $1.30 to the euro, round trip). Aurigny (aurigny.com) and Flybe (flybe.com) airlines offer daily flights to Guernsey from London Gatwick and nine other airports in Britain. Guernsey's bus network serves all of the island's major attractions. (Note: Guernsey's own currency is pegged to the British pound.)

What to see

Hauteville House (38 Hauteville, St. Peter Port; 44-1481-721-911; victorhugo.gg) is open from April to September, Monday to Saturday. Visits available only by guided tour; reservations required. Admission is 6 pounds.

Gill Girard (44-1-481-252-403; gillgirardtourguide.com; 6 pounds) leads guided walks and bus tours of the island on a variety of themes including Victor Hugo, as well as the Guernsey-set novel The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society.

The island has a 45-kilometer network of clifftop footpaths that follow the rugged coast. Maps are available at the information center (44-1481-723-552; visitguernsey.com).

Where to stay

Steps away from Hauteville House, the Pandora Hotel (Hauteville, St. Peter Port; 44-1481-720-971; pandorahotel.co.uk; from 47 pounds), where Hugo's mistress Juliette Drouet lived, offers flowery, salmon-pink rooms that are comfortable, if a little shabby.

Old Government House (St. Ann's Place, St. Peter Port; 44-1481-724-921; theoghhotel.com; from 125 pounds), a former governor's mansion, offers luxurious rooms in the center of town.

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|