With thanks to Shanghai

Updated: 2011-11-04 08:48

By Chen Weihua (China Daily)

|

|||||||||

|

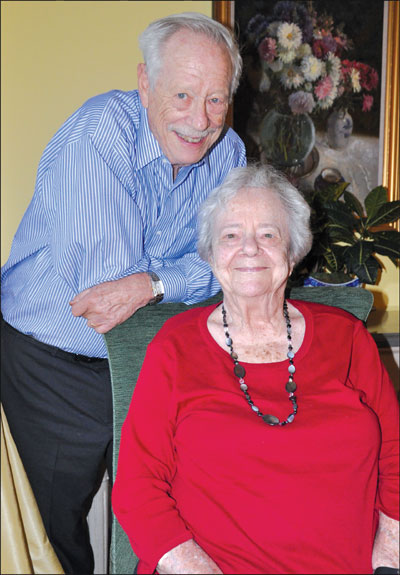

Werner Michael Blumenthal, former US Secretary of the Treasury, and his sister Stefanie Blumenthal Dreyfuss. Chen Weihua / China Daily |

Fleeing tyranny in Germany 72 years ago, Michael Blumenthal's family found refuge in Shanghai ghetto

Relaxing on a couch in his 17th-floor apartment in Park Avenue, Upper East Manhattan, New York, Werner Michael Blumenthal, Secretary of the Treasury under President Jimmy Carter, says his view of China now is totally different from the eight years he grew up in the Shanghai Jewish ghetto.

After Kristallnacht in late 1938 when Jews were attacked throughout Nazi Germany, Blumenthal's parents fled the country. They boarded a ship in Italy and it took them a month to arrive in Shanghai in 1939, then the only place in the world that did not require an entry visa.

While Shanghai was known to many as a paradise for adventurers or oriental Paris in the early 20th century, teenage Michael found it an unpleasant place.

"Shanghai in those years was not a good place. Part of Shanghai was occupied by Japanese. Shanghai was a lawless and dirty place, with many, many poor people, refugees from the countryside. Many people were sick and many died on the streets. There were diseases, corruption and prostitution."

About 18,000 Jewish refugees from Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia and other places went to Shanghai in those years. "Nobody came because they wanted to. They all came because that was the only place you could go If you stayed in Germany you would be killed," Blumenthal, 85, says.

"We were arriving not knowing what would happen to us and how long we would stay," says Stefanie Blumenthal Dreyfuss, 89, his sister. "There was a war and we were hoping we would be able to get a job."

Not among the poorest Jewish refugees, Michael's parents were able to rent a place first near Weihai Road in the better part of the city. Michael attended a school in Bubbling Well Road, now known as Nanjing Road West, and Stefanie found a temporary job working as governess in a British family.

Things turned worse after the Pacific War broke out at the end of 1941. By 1943 the occupying Japanese army forced the 18,000 stateless Jews in Shanghai to a crowded 2-sq-km area of Hongkou district, known as Little Vienna or Shanghai ghetto, where the Blumenthals' former home at 59 Zhoushan Road still stands with a commemorative stone tablet.

In 1942 Michael had to quit school and worked a number of jobs including one in a chemical lab owned by a Swiss.

"While we were there, we were poor, not having enough to eat and not enough clothing during the war," recalls Stefanie, who is visiting her brother from her home in Connecticut.

On Aug 15, 1945 when Japan surrendered, Michael and Stefanie found better paying jobs working for Americans; Michael at an air force facility and Stefanie at a development program under the State Department.

Michael remembers that with more money after the war, he was able to enjoy the wonderful Chinese food in restaurants in Nanjing Road.

Both Michael and Stefanie say they are thankful to the Chinese people. "Shanghai saved our lives; it was very important," Stefanie says.

"Even the Chinese had no control of Shanghai," Michael says. "They could make our lives difficult because Shanghai was a Chinese town. I don't think we owe Japanese any thanks because they didn't treat us very well during the war." But then he adds: "We owe some thanks because they didn't mind us coming in the first place."

Like most foreigners in Shanghai in those days, Michael and his family did not have much interaction with the Chinese community. "One thing that made me very sad was that very few of the refugees had any interaction with Chinese people. That was not very smart and that was very unfortunate."

"We all thought our stay in Shanghai was going to be interim and we would all go some place else," Stefanie says.

To Michael, it was also because the Jews were copying other foreigners - the British and Americans who looked down upon Chinese.

"I learned a little Chinese, Shanghai dialect, so I could talk to a rickshaw coolie and people at grocery stores," Michael says. His few words of Shanghai dialect smack of the accent in old days.

"I learned more about China after I left there than when I was there. When I was a young man I made the mistake like many people. When I was Secretary of the Treasury I went to negotiate with Zhou Enlai and Deng Xiaoping, I opened the US embassy in Beijing, I knew Jiang Zemin and all these people. I learned a lot about China.

"I feel in my later life that I learned a lot of valuable things while in Shanghai. Today as an old man looking back, I (say) 'Pretty good time'. China has been part of my life."

He and his sister describe themselves as two lao shanghai ning, the Shanghai dialect for old Shanghainese.

After waiting for about two years after World War II, Michael and Stefanie boarded the US SS Marine Adder in Shanghai in September 1947 on a 17-day journey to San Francisco.

He described his feeling in his book The Invisible Wall: Germans and Jews. "It was the last leg of an odyssey that had begun with their headlong flight from Nazi terror, in the wake of Kristallnacht with its smashed shops, burning synagogues, and concentration camps of almost a decade before. Finally, the long, circuitous journey was coming to an end. The Marine Adder was the Ark delivering them to dry land, to a permanent home and to renewed hope."

Michael found the United States a land of opportunity. After graduating from the University of California at Berkeley in 1951, he received scholarships to attend Princeton University, where he received a PhD.

He worked in the private sector and then in the State Department in the 1960s as adviser to President John F. Kennedy and President Lyndon Johnson on trade. He returned to the private sector and Jimmy Carter appointed him Secretary of the Treasury in 1977.

Now spending most of his time in Princeton, New Jersey, and also traveling much to New York and Berlin, where he is director of the Jewish Museum Berlin, Blumenthal says he now has more perspectives on his days in Shanghai. "You think back and you see there are some good things. It saved our lives. We did meet some nice people, friendship that you kept for the rest of your life. I didn't know much about Chinese culture, but I did learn about the Far East and something about China."

He believes that is why in 1973 he was invited to be chairman of the National Committee on United States-China Relations, an NGO that promotes understanding and exchanges between the two countries.

He says that if he had not stayed in China as a teenager he would not have the kind of understanding he has of it today. "China today is much, much better. I think China is a miracle. Chinese people (have made) a leap from the 19th century to the 21st century. It's a fantastic accomplishment. It has been done with a lot of hard work and intelligence. I don't think any other country could have done that.

"You have to admire them. I think Chinese people are wonderful and talented. They have demonstrated they can do a lot of things better than we can."

He says he is optimistic about the bilateral relationship between the two countries. "I think it's a pretty good relationship. We accommodate each other because we know we have to live together in this world."