He fought for the future

Updated: 2015-08-08 01:39

By HATTY LIU in Vancouver(China Daily USA)

|

||||||||

|

|

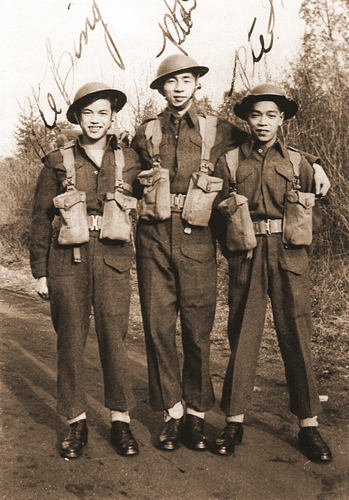

Bing Wong (left) with Dan Chan (centre) and Daniel Wong during guerilla training in Saskatchewan, Canada in 1945. Provided by CHINESE CANADIAN MILITARY MUSEUM |

Island fishing village

Wong said that when he was a child, his father moved the family to Alert Bay, BC. The fishing village on a small island off the northeastern coast of Vancouver Island was the traditional territory of the Namgis First Nation.

“Somebody my father knew went there for work, and he said the First Nations were so good to the Chinese, so my father moved the whole family there,” Wong said. “He said he wanted to raise the children in an atmosphere where there was no discrimination.”

The Wongs were one of three Chinese families in Alert Bay, who made up a “Little Chinatown”, Wong said.

They were friendly with the First Nations community, who were customers at Wong’s father’s general store. They also got along with the families of Japanese fishermen who lived in the area until they were removed to the internment camps under the War Measures Act in 1942. Growing up, Wong played “Cowboys and Indians” with the indigenous children.

“I played the Indian, all the time — they wanted to be the cowboys,” he said with a laugh.

Wong went to the mainland to attend high school at Vancouver Technical School, where he trained as an air cadet. His brother, Frank, was one of the few Chinese in BC accepted into the army near the start of the war and participated in the D-Day landing at Juno Beach.

Having originally wanted to be a pilot or navigator in the Air Force, Bing Wong enlisted shortly before the Chinese were called up under the National Resources Mobilization Act because he heard that those who joined early could pick a branch of the military to serve in.

“Back then, everyone wanted to fly airplanes,” he recalled. “But only the top recruits got to do that. So then, I wanted to join the Armoured Corps, but it turns out once you joined [the military] they got to decide where to put you, and they needed infantry.”

Like many other Chinese in the Canadian Army, Wong was soon recruited to conduct special operations behind enemy lines in Japanese-occupied territories in Asia.

“I went in for the interview with the captain, and he told me, ‘Your Chinese is lousy,’ ” he chuckled. “A lot of the Canadian-born Chinese were like that: I spoke Cantonese at home with my mother, but I didn’t really read or write it, and I went to the regular [English] schools.”

Nonetheless, Wong was assigned to a three-person team with Dan Chan and Daniel Wong (no relation). They were expected to get parachuted together on their missions.

Wong was the team member responsible for handling the ammunition, guns and explosives, which he would eventually be training local guerillas in Asia how to use. Daniel Wong learned to operate the radio and communicate in code.

Chan, who could read and write Chinese, was sent to take a six-month Japanese language course in order to train as a language specialist.

It was because they had to wait for Chan to finish his course that the three were still in Canada in May 1945, when most of the other Chinese in the special operations and other parts of the military had gone overseas.

As the war in Europe drew to the close, an order came calling for volunteers to join the Canadian Army Pacific Force (CAPF), the expeditionary unit that would be sent to participate in the attack of Japan.

- Some 200 migrants believed dead in Mediterranean shipwreck

- Chinese FM rejects Philippine, Japanese, US claims on South China Sea issue

- 'Major breakthrough' may help solve riddle

- Hiroshima marks 70th anniversary of bombing

- World 'watching' Japan's next move

- Migrant boat capsizes in Mediterranean, at least 25 dead

30 historic and cultural neighborhoods to visit in China

30 historic and cultural neighborhoods to visit in China

Beijing Museum of Natural History unveils 'Night at the Museum'

Beijing Museum of Natural History unveils 'Night at the Museum'

Sun Yang wins third consecutive 800m free gold at worlds

Sun Yang wins third consecutive 800m free gold at worlds

Aerial escape

Aerial escape

Freshmen of top universities from poorer families work part time to reduce family burden

Freshmen of top universities from poorer families work part time to reduce family burden

17 armed forces take part in Russia military contest

17 armed forces take part in Russia military contest

A glimpse of traditional Chinese business blocks

A glimpse of traditional Chinese business blocks

Top 5 most popular drones in China

Top 5 most popular drones in China

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

China willing to work with US to contribute to world peace, stability

China asks further investigation on MH370

Police fatally shoot ax-wielding man at Nashville movie theater

Study-abroad tours in US booming

Malaysia confirms plane debris is from Flight MH370

IMF to study yuan inclusion

LA clinic seeks fertility-market access

China and US discuss ways to fight terror

US Weekly

|

|