Another one on the way

Updated: 2014-02-17 09:47

By Joseph Catanzaro and Yan Yiqi in Zhoushan, Zhejiang province, and Li Aoxue in Beijing (China Daily)

|

||||||||

"They are more rational than excited," Yang said. "They did not show up eager to get pregnant. They came to learn more about the policy - to have a full understanding - and to make sure they are eligible. It doesn't mean they are going to have a baby right away."

As of January, 87 women in Zhoushan had sought permission to have a second child, and 41 were approved after the completion of a 30-day application process. "The conclusion is that not that many people are rushing into having a second child here," Yang said. "That means the low birth rate will not change overnight."

Does the slow takeup in Zhoushan suggest that women in China generally don't want a second child? Not necessarily, according to Mao Yafei, deputy head of Zhoushan Women's Hospital. At a consultation clinic to advise couples about having another baby, staff have seen a steady stream of women older than 30 who are interested but want to assess the health risks first.

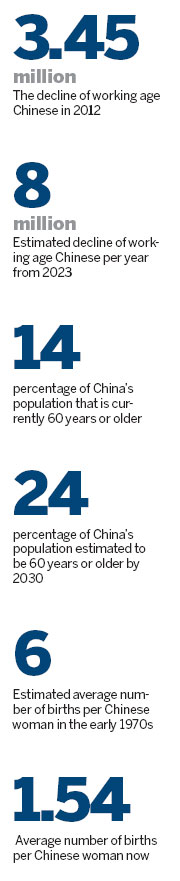

Li Jianmin, a demographer with Nankai University in Tianjin, said surveys show that about 60 percent of eligible people polled would consider having a second baby. Such figures have given birth to a number of theories at home and abroad about how effective the new policy will be as an agent for demographic change.

Nationally, officials estimate the policy change will generate about 2 million more babies each year for the next five years, on top of the current 16 million annually.

Mao said what she's seeing in Zhoushan contradicts a line being put forward by international pundits suggesting that China's labor force problem will be exacerbated in the short term by women leaving the workplace after having a second child.

"Women of an older age are asking questions about whether it's safe to work during pregnancy and how quickly they will recover so they can return to work," she said.

Public servant Zhao Zhenghao, 34, is one of the locals now planning and saving for two children. Ducking into a local Zhoushan restaurant, he said his wife, who is hoping to become pregnant with their first child this year, will not give up her career but might adjust her working hours.

"My wife will not give up her job," he said. "She can have shorter hours, and so can I."

He dismissed another view commonly bandied about by foreign sinologists: that Chinese people of childbearing age will not be able to afford a second baby because they will need to support two sets of parents and possibly even grandparents.

"Two children won't cost much more than one," he said. Besides, he said, "Both of our parents have high pensions. They earn more than we do now. I am typical of my generation in the cities. Most of our parents have jobs and pensions and can support themselves."

Wang said the issue is less about Chinese couples being able to afford the basic costs of raising a second child than it is about whether they can afford to give the children the top-notch education and financial support that has become typical in the past three decades.

Another factor is lifestyle: Many Chinese will not want to sacrifice their personal prosperity for children.

Moreover, a substantial chunk - 37 percent - of China's population, mostly in rural areas, has long been exempt from the one-child policy, and most already chose to have a second child. It is the urban-dwelling, modern Chinese women who will need to have more children if the plummeting birthrate is to be meaningfully addressed, Wang said.

World's largest freshwater lake frozen

World's largest freshwater lake frozen

American photographer wins World Press Photo 2013

American photographer wins World Press Photo 2013

Zhou Yang retains women's 1500m title

Zhou Yang retains women's 1500m title

Renzi set to become Italy's youngest PM

Renzi set to become Italy's youngest PM

Kissing contest celebrates Valentine's Day in Beijing

Kissing contest celebrates Valentine's Day in Beijing

Xinjiang quake damage could have been worse

Xinjiang quake damage could have been worse

US East Coast buried in snow

US East Coast buried in snow

China's Li wins women's 500m gold

China's Li wins women's 500m gold

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Shelters reveal flaws in child welfare

Precipitation expected to clear up smog-filled skies

Police reveal details of Xinjiang terrorist attack

Canadian immigration changes called unfair

Finding real wealth in health industry

Courts try to improve efficiency

Europe eyes new data network

Obama signs increase in US debt ceiling

US Weekly

|

|