Healing old wounds in a medical melting pot

Updated: 2015-06-12 07:31

By Zhang Yu and Pei Pei(China Daily)

|

||||||||

After Liu Shiyue lost almost everything he held dear during Japan's occupation of China, his hatred for 'the invaders' was intense and long-lived. However, years later when he worked with a group of Japanese physicians, the Chinese ophthalmologist gradually learned how foes can become friends, as Zhang Yu and Pei Pei report from Shijiazhuang.

Editor's Note: This is the fifth in a series of special reports about the experiences of foreigners who either lived or served in China between 1937 and 1945.

The hardest time in Liu Shiyue's life came in 1945, when he discovered that his mother had been murdered three years earlier.

In 1942, Liu's mother was killed in a fire set by Japanese soldiers during the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression (1937-45), but because the war had separated them, the boy didn't learn about her death until he was 12.

Born in 1930 in Shanxi province, Liu joined the army at age 8 and was sent to the front, and although he was too young to handle a weapon, he toured the battlefields as a member of a propaganda team. "My job was to give cultural performances to comrades and spread news about the progress of the war to residents of rural areas." he said.

The job gave him a firsthand view of the atrocities committed by the Japanese troops.

"I had seen so many injuries and deaths caused by the Japanese that I couldn't shed my intense hatred of them until later in life," he said.

"Although I survived the war, seven members of my family, including my mother, were burned to death by the Japanese," he said. "One time (when the Japanese entered the village), I narrowly escaped death myself," he said, adding that he only survived by hiding beneath a dead sheep for an entire night.

Liu's father also survived the war. "My father served in the army as a doctor. He was at a medical center far away from home at the time." Liu said.

According to Liu, his father treated tens of thousands of wounded soldiers: "My father was my role model. I wanted to become a doctor like him and save lives."

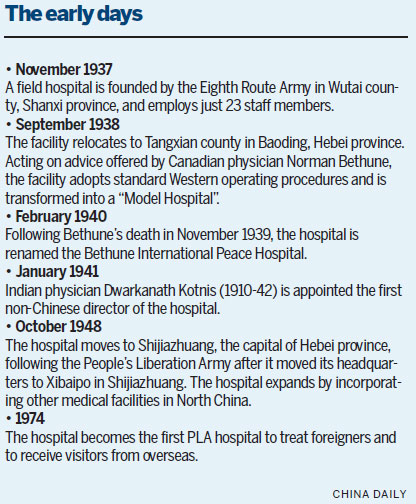

When the war ended in 1945, Liu began studying medicine. When he graduated, he served as a general physician during the Chinese Civil War (1945-1950), and later worked as an ophthalmologist at the Bethune International Peace Hospital in Shijiazhuang, the capital of Hebei province, which had originally been an Eight Route Army field hospital for wounded soldiers in the Shanxi-Chahar-Hebei region, an important anti-Japanese military base.

After his wartime experiences, Liu was shocked and deeply unhappy when 120 Japanese medical staff arrived to work at the hospital in 1951. At the time, Liu's hatred of the Japanese was so strong that he had difficulty working with them or even regarding them as colleagues. "Their faces always reminded me of the evil deeds committed by the Japanese troops," he said.

The 120 Japanese included 45 doctors, 34 nurses, eight pharmacists, and a small number of administrative staff, who worked at the hospital until 1953, with several holding top positions, according to hospital records.

Liu's attitude toward his new colleagues gradually changed, thanks to his wife, Fu Huimei, who had been born in Japan and lived there with her parents before moving to China during the Japanese occupation. Fu also worked at the hospital, and she helped her husband to forge friendships with the Japanese visitors.

Fu's superior at the hospital was a Japanese dentist called Kazumichi Inoue, who worked at the hospital for seven years, from 1946 to 1953. Inoue's enthusiasm and masterly treatment of patients won him great acclaim from both soldiers and the local civilian population.

In addition to his routine work on the wards, Inoue also taught. He trained nearly 100 dentists during his stay in China, and many of his former students became the backbones of hospitals in the Beijing Military Region during the 1980s.

Fu spoke Japanese fluently, so she was regularly invited to translate correspondence and records for various hospital departments, including the eye clinic where Liu worked.

"My wife's translation skills made it easier for me to communicate with the Japanese doctors, and I gradually came to realize that they were responsible, careful people. They were not the same as the Japanese invaders. My attitude toward them began to change, and I even made friends with several of them," Liu said. "One of them once called me from Japan just to tell me that he was excited because a Chinese team had won a table tennis competition in Japan."

Those Japanese visitors bonded with China and the hospital, according to Liu. They cared about the development of the country and the hospital, even after they returned to Japan, and many have returned several times to visit their former workplace and colleagues.

As confirmation of her husband's view, Fu quoted one of the returnees: "China is our second home. We love the Bethune International Peace Hospital and we miss our colleagues and comrades."

Susumu Omiya, one of the most frequent returnees, has visited China every second year since 1993, and she was instrumental in helping the hospital to establish a working relationship with the Saka General Hospital in Shiogama, Miyagi prefecture, Japan, in 1999.

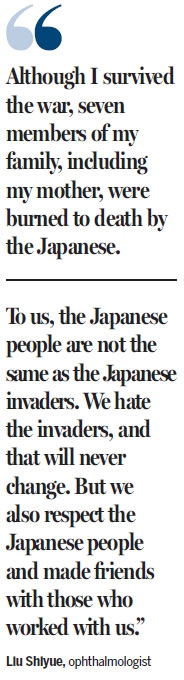

"To us, the Japanese people are not the same as the Japanese invaders. We hate the invaders, and that will never change," Liu said. "But we also respect the Japanese people and made friends with those who worked with us."

According to Fu, one of her colleagues, Masako Torikai, once told her, "After the Japanese troops surrendered, the Chinese Communist Party recruited some Japanese medical workers like me, who had served in the Japanese army in Northeast China."

Most of those who remained were anti-war, and they chose to stay in China rather than return home. Torikai said she had seen the misery and pain the war had brought to the Chinese people. She wanted to help save lives, so she didn't hesitate to stay and join the PLA Army, according to Fu, who remembered her saying, "The Japanese and their Chinese colleagues are like siblings."

Bethune's legacy

The forerunner of the Bethune International Peace Hospital was founded in 1937 during the Japanese occupation. "I was honored to work there because it was partly established by Doctor Norman Bethune," said Liu, who worked at the hospital for half a century.

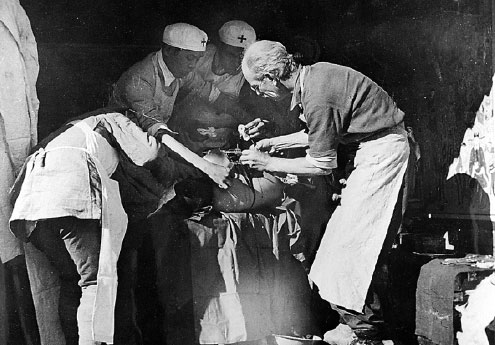

The name of Norman Bethune (1890-1939) is still famous throughout China because of the medical aid he provided for Chinese troops during the occupation. The Canadian physician, who arrived in China in 1938, treated both civilians and wounded soldiers. To provide better treatment for the troops, he expanded and relocated a small field hospital originally established by the Eighth Route Army, transforming it into a "Model Hospital" in the village of Songyankou, Shanxi province. A large number of physicians subsequently trained at the hospital and joined Bethune's rescue team.

A great internationalist

Bethune's period of activity was short-lived, however. In 1939, he contracted a skin infection from a wounded soldier and died of septicemia a short time later in Tangxian county, Hebei. In 1940, the Model Hospital was renamed The Bethune International Peace Hospital to commemorate the Canadian as a great internationalist.

The hospital records show that more than 11 million wounded soldiers were treated during the eight years of war, and 1,500 doctors were trained at the establishment.

"The duty of a doctor is to help patients in their fight back to health and strength." That quote from Bethune is displayed on the walls at the Bethune Memorial House, which was opened in 1975 and stands in the grounds of the hospital. Those words often inspired Liu, who always tried to provide his patients with the best possible treatment.

"I survived the war, and I know how Bethune fought to save our wounded soldiers." he said, adding that he and many of his colleagues revere Bethune's memory and have devoted themselves to passing his teachings onto the younger generation.

Now 85, Liu spent 50 years treating patients with eye conditions and has helped tens of thousands to regain their sight. Although he officially retired in 1994, he regularly visits local hospitals in Hebei as a volunteer to train young ophthalmologists. This year he made an emotional return to the Peace Hospital, where he treated patients but didn't charge them or the hospital for his services.

"Sometimes I even apply to the hospital on behalf of my patients so they can enjoy free treatment. Some are too poor to cover the medical expenses, and I am always sad when I discover that people have been forced to sell their belongings to pay for treatment," he said.

According to one of his former colleagues, Liu once explained that the ophthalmic department charged the lowest fees in the hospital, not because it received fewer patients, but because the team had adhered to his dictum of saving the patients' money whenever possible. The staff remember how the veteran physician once told his colleagues: "If you can charge 1 yuan, don't charge 2 or more; if you can treat patients without charging, then just do your doctor's duty for free."

Following in Bethune's footsteps, the hospital treats patients free of charge, and in 2012 it initiated a program of annual free visits to war veterans and cash-strapped rural residents.

At the end of May, the hospital cooperated with a team of Canadian ophthalmologists to provide free eye examinations for residents of the areas around the old revolutionary base. In 1974, it became the first PLA hospital to admit foreigners, and since then nearly 30,000 people from more than 80 countries have visited the hospital and the memorial house. At present, the hospital boasts more than 2,000 beds, provides more than 1.05 million outpatient consultations, and treats 51,000 inpatients every year.

Hospital official Liu Huibin praised the commitment of the medical staff throughout the hospital's history: "The wartime Bethune has left us, but we now have many Bethunes at the hospital. Liu Shiyue is typical of the type. His loyalty and dedication to the patients always impressed his colleagues."

For Liu Shiyue, the virtues upon which the hospital was founded will live forever: "The soul of Norman Bethune will never die because it lives in every generation of medical workers at the hospital he helped to found."

Contact the writer at zhangyu1@chinadaily.com.cn

|

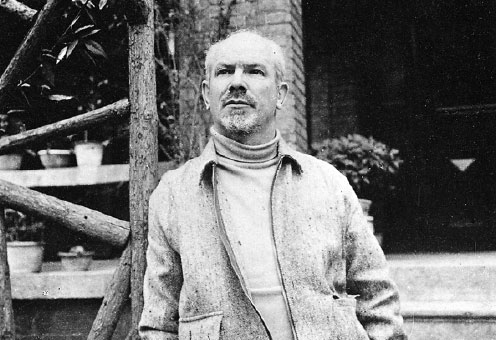

Canadian physician Norman Bethune (1890-1939) is famous throughout China because of the medical aid he provided for Chinese troops during the Japanese occupation. Li Xue / for China Daily |

|

Norman Bethune performs surgery on a wounded soldier at Laiyuan in the Shanxi-Chahar-Hebei border area. He also helped to expand a small field hospital founded by the Eighth Route Army. Xinhua |

|

Liu Shiyue and his wife Fu Huimei. Fu, who was born and raised in Japan, moved to China during the Japanese occupation. She became a bridge between Liu and his Japanese colleagues. Provided to China Daily |

|

Liu Shiyue (right), conducts an eye checkup on Susumu Omiya, one of 120 Japanese medical staff who arrived to work at the hospital in 1951. Provided to China Daily |

(China Daily 06/12/2015 page6)

Top 10 investor countries and regions

Top 10 investor countries and regions

Beijing showcases Olympic exhibits and visions

Beijing showcases Olympic exhibits and visions

Ten photos you don't wanna miss - June 11

Ten photos you don't wanna miss - June 11

Youth of today in Sudan

Youth of today in Sudan

EU sanctions hamper Italian-Russian commercial ties: Putin

EU sanctions hamper Italian-Russian commercial ties: Putin

Across Canada(June 11)

Across Canada(June 11)

US dollar inspired art to be auctioned at Sotherby

US dollar inspired art to be auctioned at Sotherby

Coffee shop where Premier Li met entrepreneurs

Coffee shop where Premier Li met entrepreneurs

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Carter greets General Fan at Pentagon

Pentagon to greet General from China

Helping the Hill understand China

Suu Kyi begins groundbreaking visit

Michelle Kwan to work for Hillary Clinton campaign

China, US take fresh views on TPP and AIIB

G7 accused of ignoring the facts over South China Sea

Obama weighs sending several hundred more US troops to Iraq

US Weekly

|

|