Testing times for student admissions

Updated: 2013-01-22 07:42

By Feng Xin (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

Zhang Lingxiao (left), a native of Chongqing, studies at a high school in Jinjiang, Fujian province. The Fujian government issued a policy allowing nonresident students in the province to take the college entrance examination there in 2014 as long as they complete their three-year high school education in the province. They can also enjoy the same treatment as the local residents. Zhang Guojun / Xinhua |

|

Nonresident parents gather in front of the Beijing Education Examinations Authority in late December, petitioning for their children. Feng Xin / China Daily |

University candidates who don't have hukou, or household registration, in major cities have to take the entrance exam in their home provinces. Their parents are uniting to change the situation, as Feng Xin reports.

Nonresident parents in Beijing have been signing a petition to fight a policy that will continue to limit their children's eligibility to take the national college entrance exam in the city. Twenty-six of them jointly submitted a formal request for an administrative review to the Ministry of Education on Jan 11.

This came after the Beijing Municipal Commission of Education issued what it called a "transitional" policy on Dec 30, under which nonresident children cannot take the college entrance exam in the city within the next two years.

"I was angry and heartbroken," said Meng Fanling, a nonresident mother and parent volunteer in Beijing. "Our efforts and fighting for all these years have turned into nothing."

For the past three decades in China, high school graduates could only take the national college entrance exam, known as gaokao, in their home provinces, where their household registration, or hukou, were issued. But one in six Chinese citizens no longer lives where their hukou is registered, according to figures from the National Bureau of Statistics for 2011.

Having to return to one's home province to be eligible to take the exam has been a huge burden for hundreds of thousands of families.

While nonresident parents were disappointed in Beijing's Dec 30 policy, on the other hand, Liu Yang, a native Beijinger, has been rallying opposition to these parents. His blog and micro blog have tens of thousands of followers.

"I feel sorry for the migrant families, but it is not simply an issue about education," Liu said. "It's a matter of the city's population capacity. It just cannot take in more migrants and give them equal rights."

Nonresidents' appeal

In August last year, the State Council's General Office published a directive requesting provincial governments to make policies addressing the issue before the end of 2012.

Liang Shuangcai, a nonresident father, has been visiting the Beijing Municipal Commission of Education's Office of Complaints and Appeal every Thursday morning since the directive came out.

Liang moved to Beijing 12 years ago from Henan province. He works as an auditor, and has an 11-year-old son who grew up in the capital. "We will be facing the problem very soon," he said.

The Beijing policy published on Dec 30 only allows nonresident children to take the entrance exam for secondary vocational schools, starting from 2013, and higher vocational schools, in 2014.

Du Guowang cannot wait. His son is supposed to take the exam in June, and the boy may have missed his chance to do so.

In late October, Du and other parents asked the Beijing Municipal Commission of Education whether their children can take the 2013 exam in the capital.

Du said they received a letter from the commission on Nov 14, which said it is still waiting for information from the Ministry of Education, and parents should keep tracking information updates online.

While awaiting a final decision, Du tried to register his son's name on the website of the Beijing Education Examinations Authority on Dec 2. He said he successfully registered and paid the registration fee online after receiving an electronic confirmation.

He then spread the word to other nonresident parents, who found they could do the same, he said.

However, the new policy announced on Dec 30 stipulated that nonresident children are not eligible for the 2013 exam.

By that time, Du's son and a dozen other children had missed the registration deadline in their home provinces, he said.

On Jan 11, Du and another 25 parents - four parents of high school students and 22 of middle school students - jointly submitted a formal request for an administrative review to the Ministry of Education. It asks the ministry to hold the Beijing commission accountable for failing to inform the parents and students before the registration deadline. The parents believed the authorities should also provide measures for students who missed the registration in their home provinces.

Two days later, the ministry told Du that parents also needed to hand in a letter of authorization to their lawyer, and their children's permission for an appeal on their behalf, before the ministry can decide to grant the parents' request.

The commission said the registration procedures this year are no different to previous years: Only when candidates complete both online registration and in-person confirmation will they be successfully registered. The commission also said it made it clear in its online question-and-answer section two days before the registration started that nonresident students were advised to register in their home provinces. It did not comment on whether it is responsible for such students missing their home provinces' deadlines, or when Beijing's final policy will be made.

Meanwhile, Du and the parents are preparing all the legal documents required to appeal to the ministry again in late January.

Concern in capital

Liu Yang, the Beijing native, fears that if the capital loosens its hukou restraints on the migrant population, growing numbers will flood into the city.

He said some may even become "gaokao immigrants", referring to those who try to become Beijing residents to enjoy the city's higher-education resources.

Zhu Yongxin, a member of the National People's Congress' Standing Committee - China's top legislative body - has been studying the issue since 2006. He sent a proposal addressing it to the education and public security ministries during China's two political sessions in 2012.

Zhu said metropolises attracting "gaokao immigrants" is a possibility. "But reality is reality. It's not easy at all to move to a city like Beijing," he said, citing high housing prices and living costs.

While Zhu is satisfied that most Chinese provinces issued policies to tackle the problem before the deadline, he believes metropolises could have introduced more lenient rules for long-term taxpayer families.

"It's a matter of civil rights," Zhu said.

Three patterns

According to media reports, as of a week after the deadline set by the State Council, all provinces on the Chinese mainland except Qinghai and the Tibet autonomous region announced their policies.

Yang Dongping, an education professor at the Beijing Institute of Technology who is also involved in reforming China's college entrance exam system, divides the provincial policies into three patterns.

First, more than half of the provinces, like Hebei, Heilongjiang and Fujian, set the bar relatively low for nonresident students. Candidates only need to provide a complete middle school or high school record to be eligible for entrance exams. Some provinces also require parents to provide proof of a stable job and accommodation.

These provinces, however, are traditionally hometowns for migrant workers who leave for better opportunities. In other words, the proportion of nonresidents in the population is small, Yang said.

Second, fewer than a dozen provinces, such as Shaanxi, Liaoning and Guizhou, set the bar higher for nonresident families. In these regions, not only must students have longer school records or even hukou within the next few years, their parents also have to contribute personal income taxes and social security taxes for a certain number of years before the children become eligible.

Some of these provinces, like Guizhou, although not hotspots for migrant workers, are areas where candidates benefit from low admission scores set by universities, Yang said.

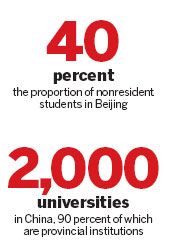

Third, the toughest regions are China's metropolises of Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangdong province. Yang said in these regions the nonresident population is large. Beijing's education commission estimates that out of its 1 million schoolchildren, 40 percent are nonresident students.

University problems

Although much of the discussion attributes nonresidents' eligibility to China's hukou system, a number of scholars point out that China's university recruitment system worsens the problem.

According to a handbook authorized by the Ministry of Education, China's universities can be divided by their administrative subordination into two categories: those managed by the ministry as well as other central agencies, and universities managed by provincial governments. There are about 2,000 universities in the country - more than 90 percent of them provincial institutions.

Every year, each university needs to submit a detailed recruitment quota plan to be approved by its supervision department. While central universities recruit students nationwide, provincial universities largely recruit students with hukou in that province.

There is no strict way to work out the student quota, as it usually depends on the university and local government's funding and the university's traditional source of students, said Xiong Bingqi, vice-president of the 21st Century Education Research Institute in Shanghai.

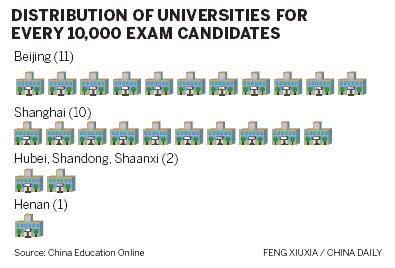

However, distribution of universities in China is extremely uneven. According to research by China Education Online, for every 10,000 exam candidates, there are 11 universities in Beijing and 10 in Shanghai. But the number drops to two in Hubei, Shandong and Shaanxi provinces and below two in Henan.

In 2011, Peking University admitted about 32 students for every 10,000 Beijing candidates but less than one in Henan, Hubei and Shandong provinces. That is to say, Beijing's exam candidates are 47 times more likely to be admitted than candidates from these three provinces.

Xiong said, "This province-based recruitment system is an unfair one to start with. It creates huge geographical discrepancies and relies heavily on local government's administration."

Because of this, many local residents fear their children's chances of being admitted to good universities will be diminished, Xiong said.

But Yang Dongping, the Beijing Institute of Technology professor, said metropolitan residents should not be too worried, because the number of university candidates has been declining. The geographical discrepancy in recruitment can be partially corrected by pushing the central universities to give a fairer quota to different provinces.

What really matters is the capacity of primary and secondary educational resources in mega-cities, Yang said.

He cites figures from Beijing's education commission, showing that by 2020, primary schools will need 300,000 more places, and middle schools 115,000,

"That's the case without lifting the hukou limits for nonresident students," Yang said.

It is hard to predict accurately how many more nonresident students Beijing will have, and therefore it is necessary for the government to be cautious and take time to monitor policy effects, Yang said. "It's easier to talk about constitutions than thinking about realistic questions," he said.

The question then comes down to an essential one: Do people only have one option between constitutional rights and population control?

"No, definitely not," Yang said.

Although issues like natural resources, traffic pressure and mega-cities' functions are all problems to tackle, they only demonstrate the degree of difficulty in addressing nonresident students' exam eligibility rather than serving as the basis for policymaking, Yang said.

"Attempting to control population by limiting education is never the way to go," he said.

Contact the writer at fengxin@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily 01/22/2013 page6)

In Photos: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan

In Photos: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan

Li Na on Time cover, makes influential 100 list

Li Na on Time cover, makes influential 100 list

FBI releases photos of 2 Boston bombings suspects

FBI releases photos of 2 Boston bombings suspects

World's wackiest hairstyles

World's wackiest hairstyles

Sandstorms strike Northwest China

Sandstorms strike Northwest China

Never-seen photos of Madonna on display

Never-seen photos of Madonna on display

H7N9 outbreak linked to waterfowl migration

H7N9 outbreak linked to waterfowl migration

Dozens feared dead in Texas plant blast

Dozens feared dead in Texas plant blast

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Live report: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan, heavy casualties feared

Boston suspect cornered on boat

Cross-talk artist helps to spread the word

'Green' awareness levels drop in Beijing

Palace Museum spruces up

First couple on Time's list of most influential

H7N9 flu transmission studied

Trading channels 'need to broaden'

US Weekly

|

|