A college course opened his world to China

Updated: 2014-05-23 11:52

By Chen Weihua in Washington (China Daily USA)

|

||||||||

|

Kenneth Lieberthal, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution in Washington, has spent most of his career as a professor of Chinese politics. His China connection began when he decided to take a course on China at Columbia University. Sun Chenbei / China Daily |

"Are you grading my presentation?" Donilon asked, triggering laughter among the audience.

Lieberthal told China Daily after the talk that it was an embarrassing moment.

However, the 70-year-old has spent most of his career as a professor of Chinese politics despite his years at the Brookings and service in President Bill Clinton's White House as special assistant to the president for national security affairs and senior director for Asia on the National Security Council.

And the University of Michigan, where Lieberthal had worked for 26 years, announced it will rename its Center for Chinese Studies as the Kenneth G. Lieberthal and Richard H. Rogel Center for Chinese Studies to honor its respective former scholar and financier for the center. A celebration of the renaming will be held in Ann Arbor on Oct 16.

But for Lieberthal, his China connection started as an accident.

As an undergraduate at Dartmouth College in the early 1960s, Lieberthal spent much of his time studying Soviet affairs. He then pursued his studies at Columbia University when his adviser, Zbigniew Brzesinski, who later became the National Security Advisor under President Jimmy Carter, told him that he had already covered pretty much what Columbia could offer in Russian studies. He advised Lieberthal to take something else.

Checking on his schedule, Lieberthal found a course on China offered by Doak Barnett, a prominent scholar on China. Knowing nothing about China, Lieberthal thought it might be interesting to find out.

"So I took that course with Doak and just became absolutely fascinating," Lieberthal recalled.

Barnett encouraged Lieberthal to join the East Asian Institute and do a program on Chinese language and politics on his way to his doctorate degree.

Then 22-year-old Lieberthal followed his advice. He was fascinated with comparing the Chinese and Soviet revolutions.

"And it became one of the most fortunate decisions I have ever made, because I have enjoyed going to my office every day throughout my career," Lieberthal said.

While still keeping an interest in the Soviet Union, his research interest turned to China. That included studying Chinese language starting in the summer of 1966 and then conducting a six-month language program in Taiwan in late 1969 before moving on to Hong Kong for a year of his dissertation research.

Then Hong Kong was the closest place to the Chinese mainland that Americans could go. Lieberthal's research was on the revolution in the city of Tianjin, from the 1930s up to the Three Antis and Five Antis Campaigns in the early 1950s.

He delved into the Tianjin revolution by researching on the early studies by Nankai University and good collection of materials in Hong Kong about China and talking to a wide range of immigrants in Hong Kong from Tianjin. But it was difficult for him to talk to some dock workers from Tianjin because some of them were then secret society members, which was banned in colonial Hong Kong.

Lieberthal was unable to travel to the Chinese mainland until a decade after he began his China study. It was in the summer of 1976, a trip that Lieberthal never forgot.

As a China specialist and a professor at Swarthmore College, Lieberthal went with Jan Berris of the National Committee on US-China Relations in a Congressional staff delegation. Just hours after their arrival in Beijing, the catastrophic Tangshan earthquake happened, killing more than 200,000 people.

While the agenda in Beijing was somewhat cut short due to the devastation there, the group traveled to Henan and Shanghai.

Since then, Lieberthal not only goes to China every year, in many years he goes between five to 10 times. He has given up counting the number of trips but said it might be 200.

Lieberthal enjoyed his teaching job, describing his 11 years' teaching at Swarthmore College from 1972 to 1983 as a "fabulous experience." His class on Chinese politics drew 35 students, a big size at the elite liberal art college where the average class size is 15.

When Lieberthal taught at the University of Michigan for more than 20 years from 1983, his largest lecture course had 540 students.

He then focused entirely on China's political system and had no interest in studying Chinese foreign policy, until he took a sabbatical leave in 1975 to work at Rand Corporation on Sino-Soviet relations in the late 1960s.

His later interest in US and China foreign policy also had to do with Michael Oksenberg, a China hand whom Lieberthal described as his mentor and friend.

Oksenberg, who played a major role in the full normalization of diplomatic ties between China and the US when he served as a senior staff member at the National Security Council in the Carter administration, would call Lieberthal from time to time to discuss issues.

"Then I became interested in US policies towards China," Lieberthal said.

However, with two sons in grammar school and high school, Lieberthal was not ready to leave them behind in Ann Arbor to serve in the government when he was offered some serious positions on five different occasions."So I waited," Lieberthal said, recalling that in 1996 he told his wife that he would love to be the China director at the National Security Council because he thought it was the best job out there.

In 1998, Liberthal got an unexpected call. It was from James Steinberg, the then deputy national security advisor, who wanted to see if he was interested in the position of senior director for Asia at the National Security Council.

Lieberthal came to Washington to meet then National Security Advisor Sandy Berger, discussing a wide range of issues during two and a half hours of "interview."

Although Berger told Lieberthal that they would let him know in two weeks, Lieberthal received a call the following day for the offer. "That was great, totally unexpected," Lieberthal recalled.

The professor of Chinese politics had a good introduction to the White House. When President Clinton traveled to China, Lieberthal received a call from his boss Berger, asking him to read and comment on a speech that Clinton was about to give. He was excited to find later that Clinton adopted all the changes that he had suggested.

At that time, the US was focused on the financial crisis in Asia and China was not at the center of the US agenda. Lieberthal felt then the US was beginning to pay a price not paying enough attention to what was going on in China.

He sat down with Berger to discuss what the US should do with China following Clinton's trip there. The new focus became negotiating for China's accession to the World Trade Organization.

While people like Charlene Barshefsky, then US Trade Representative, played a major role, Lieberthal said it then became the central focus of US China diplomacy.

But a huge crisis took place in the bilateral relationship.

It was on the evening of Friday, May 7, 1999, when Lieberthal and his wife, Jane Lindsay, were about to go out for the first time in a month for a concert at the Kennedy Center when the phone rang. It was from the White House Situation Room, informing him that the Chinese embassy in Belgrade was bombed by US-led NATO forces.

The incident, which killed three Chinese reporters, sparked outrage among the Chinese, with mass demonstrations in several Chinese cities. Despite the US apology for the accident, many Chinese believe it was a deliberate act by the US.

"The reality is we did not do it intentionally," Lieberthal said. "It made no sense, given what we were trying to accomplish with China then, to bomb the embassy in Belgrade,"

He described the bombing as things of lower probability going wrong at the same time, but he acknowledged that over the years, he has failed to convince the Chinese that it was not an intentional act.

Now a senior fellow in foreign policy and global economy and development at the Brookings, Lieberthal said at any given time, there were a lot of issues in US-China relationship. "But I thought we managed to keep the overall relationship in pretty good shape," he said.

To Lieberthal, top Chinese and US leaders communicate to each other better now because they see each other more often.

"I think in those respects the relationship is calmer and more subtle. And I think it has a much stronger base, and is more much institutionalized, than the media in each of countries treat it," he said.

While US-China relationship is not one between allies and one between countries which have total confidence with each other, Lieberthal said it is a relationship between countries that would do better rather than do worse with each other.

He believes if the relationship become fundamentally antagonistic, it would be a huge failure on both sides and would be very costly for them in bilateral and broader issues.

The China hand said that the future of bilateral relationship is not predetermined. "It's shaped by decisions, and their consequences. So diplomacy plays a very important role," he said.

Saying that there is no foreordained outcome between rising power and existing power, Lieberthal does not think that declaring a new type of major country relationship makes it true.

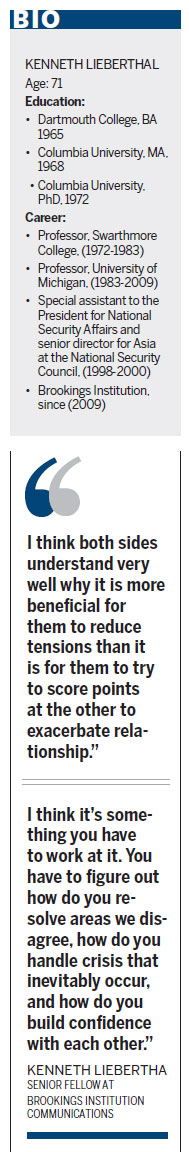

"I think it's something you have to work at it. You have to figure out how do you resolve areas we disagree, how do you handle crisis that inevitably occur, and how do you build confidence with each other," he said. "Those just require a lot of work."

Lieberthal has confidence in the leaders of the two nations in handling the relationship, describing them as serious people with considerable capability and experience.

"I think both sides understand very well why it is more beneficial for them to reduce tensions than it is for them to try to score points at the other to exacerbate relationship," he said.

But he emphasized that even if Chinese and US leaders do a good job, a crisis could still occur in other areas such as the tension between China and Japan, a treaty ally of the US.

"You can't fully control the future, but you can work hard at it," said Lieberthal.

chenweihua@chinadailyusa.com

Chinese Navy leave Pearl Harbor to join RIMPAC drill

Chinese Navy leave Pearl Harbor to join RIMPAC drill

'Cracking Tech Fortune Cookies'

'Cracking Tech Fortune Cookies'

US, China keen on fixing ties

US, China keen on fixing ties

Traditional Chinese medicine enlivens RIMPAC crowd

Traditional Chinese medicine enlivens RIMPAC crowd

Hainan provides limo service in Seattle

Hainan provides limo service in Seattle

Wanda's Chicago deal is first in US realty

Wanda's Chicago deal is first in US realty

Insurer's office to serve Chinese community

Insurer's office to serve Chinese community

Xi gives speech at SED opening ceremony

Xi gives speech at SED opening ceremony

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Chinese are No 1 buyers of US residential property

College addresses need for experts in anti-terrorism

China-US investment treaty on fast track

Minister: US 'key' to global recovery

Snowden applies for asylum extension in Russia

5 killed in Houston shooting, standoff underway

Xi: World big enough for two great nations

China, US unite against illegal wildlife trafficking

US Weekly

|

|