Reclaiming a piece of history

Updated: 2014-10-31 12:51

By Chris Davis(China Daily USA)

|

||||||||

The beautiful ancient city of Yangzhou has a glorious and glamorous past, but the storied heart of it has fallen to neglect. The mayor asked a team from Texas to help to turn it around, Chris Davis reports from New York.

Architecture projects in China that tend to steal the spotlight are usually big and flashy, like the Guangdong Museum in Guangzhou or the Bird's Nest in Beijing.

It's rare that Western architects tackle a complex urban design problem in China. Now Overland Partners, an architectural and planning firm based in San Antonio, Texas, which has been given that chance several times in China, is at it again. This time in Yangzhou, the ancient city at the juncture of the 1,100-mile-long Grand Canal and the Yangtze River.

The city began around the 6th Century as a small square surrounded by a wall, defended and nourished by canals, moats and rivers used for trade, transportation, flood control and irrigation.

As Yangzhou expanded over the centuries, a 1.25-mile-long stretch of the original moat fell to neglect. Sewer pipes ran through it. Houses and commercial buildings backed up to it and even into it, cutting off pedestrian access to the banks. People who used to wash their clothes in it, fish and paddle, lost access. Everyone, including the government, stopped paying attention.

Until Yangzhou Mayor Zhu Mingyang visited San Antonio about a year ago with a delegation to see its famed river walk and fell in love with it.

It is pedestrian friendly, no cars or bikes, just shops, hotels, shaded outdoor cafes and passenger river barges plying to and fro. The scale of it - the narrow width of the river, the closeness of one bank to the other, allowing people to see each other across the span - impressed Zhu .

Because of his company's years of being involved with the river walk, Overland Partners founder Tim Blonkvist was invited to a dinner for Zhu on a riverboat. He showed him pictures on his iPhone of some of the other river-walk projects his firm was doing in China, Nanjing, in particular, whose mayor Zhu happened to know personally.

Blonkvist said Zhu became very excited. "Can we come to your office tomorrow? I know it's Saturday, but I really want to come and talk more seriously,'" Blonkvist quoted Zhu as saying.

The mayor arrived the next day with his heads of planning, economic development and cultural affairs. They talked about river walks, not just in China, but across the globe - Venice, Chicago, Amsterdam - all of which Overland had studied extensively.

Zhu invited Overland to Yangzhou the following week to take a look at the waterway, now called the Minor Qinhuai River, which, with its 58-acre neighborhood along both banks, was almost identical in scale to San Antonio's river walk. The question was, could it be made as charming the Texas tourist magnet?

A delegation from Overland went to Yangzhou.

"When we walked it, we could understand the mayor's concern," said Jim Andrews, a principal at Overland. The so-called river "had really just become an infrastructural easement for storm water and sewage. The buildings were dilapidated, with a predominant population of aging people in very rudimentary accommodations. It was the poorest district of the city, and yet it was a stone's throw away from Slender West Lake, the city's jewel, the "equivalent of New York City's Central Park", which had just been declared a World Heritage Site.

"This was perhaps the most complex challenge we'd faced in China," he said. The site had become disconnected from the city. The river walk itself was in disrepair and didn't really connect to anything. There was no reason to be on the river at all. It was forgotten.

Overland's first step was to "listen to the landscape", dig deep into research about the city. Overland's research was also aided by maps of the city, some dating back 500 years.

Key areas

The team sorted out key areas where the river's "space" intersected with the city's "space", where each road perpendicular to the river intersected and crossed it. They called them nodes and identified eight.

Node 1 had the critically important docks where passengers boarded boats for rides to the Slender West Lake.

Node 3 had some late 1950s early 1960s factory buildings for lacquer ware that suggested an area for artists. There was an existing marketplace between Nodes 4 and 5.

They found an intriguing complex of Buddhist temples on the east bank of Node 6, as well as paper and scissor shops and book distributors. Node 7 was an agglomeration of special local eateries and restaurants. There were also existing market districts between Nodes 4 and 5 as well as between Nodes 6 and 7. Node 4, which will have a future subway stop, and Node 8, which is ideal for a tourist bus drop off, are the busiest intersections.

The planners used the "theme" of each node to create a sense of the district's identity. Where there used to be a concentration of scholars in the past, the planners considered putting schools, drawing teenagers and young adults to the site, learning there and then wanting to live nearby. Retail and other opportunities would follow.

They wanted to attract people with money in their pockets and not be just another isolated tourist attraction that so many restorations of old streets in China had become. They wanted it to be authentic, filled with real people, where shopkeepers and innkeepers aren't simply waiting for tour buses to unload. They wanted it full of the people of Yangzhou.

"It's a matter of marrying these practical, functional needs the 21st century has and try to fit that inside - in some cases - forms that come from 1,000-year-old footprints or structures," Blonkvist said.

Overland then sat down with all the interested parties to hear what they had to say.

"We learn about their aspirations and dreams for the site and what their concerns are," Andrews said. "The beauty of that is you connect with people. They're able to share their fears with you : Are you going to demolish it all? How big is it going to be? Will it overwhelm the river and surrounding area?"

Challenging stage

Andrews said that stage has been a bit more challenging in China. "It can often take time to convince people that it is a safe environment where they can express their opinions," he said.

The key piece of the project, of course, was the waterway itself, which was more than just a moat filled with water. It was a living body of water that came off the Grand Canal, snaked its way into town, made its loop and then continued on to the Yangtze River. But it was a mess.

Mayor Zhu and everyone knew that if the water quality of the Minor Qinhuai River was not significantly improved, the project would never succeed.

Overland turned to world renowned engineering company Arup, which already had several offices in China. Their landscape and water consultants who specialize in rivers and canals came up with three strategies.

They could isolate the waterway, basically turn it into a large re-circulating swimming pool, which had the advantage of total control (as long as storm water and foul inlets could be managed). Or, they could construct inflatable dams, so that at certain times - if there was a flood upstream, for instance - they could isolate the water. The third solution was a hybrid of the first two: a self-contained lock system with re-circulating water.

This solution also meant that they could provide green spaces along the river that were truly systemic systems, places that would not only function as pleasant parks, but also where water could be treated.

"One of them is a wonderful goldfish wetland areas with a series of terraced goldfish ponds and grass systems that actually help clean and aerate the water on the main canal itself," said Andrews, a place where people can "celebrate the water".

When it comes time to pitch their concept, one thing Overland does is work up a description of what the district would be like from different people's perspectives - for a tourist, someone who works on the river, someone who lives on the outskirts of Yangzhou.

"If you were in a boat and went through the project, what would you see, where would you stop and get off the boat?" Andrews said.

Overland's Blonkvist got his firm involved in China five years ago, but it's a connection that had really been 30 years in the making. It started back in 1982 when he worked for I.M. Pei at his office in New York. During the five years he spent there, he did a lot of work in Asia teamed up with a young man named Qin "QC" Chin.

One of their projects was the Singapore River master plan and marina, a contract Pei had won through an international competition. Working on that got Blonkvist interested in river walks. From there, working further with QC on the Bank of China in Hong Kong - the tallest building in Asia at the time it was built - and the US Exposition Pavillion in Beijing (which was organized by John Glenn), Blonkvist said he got to learn a lot about China.

But his - and his partners' - dream was to open a practice in San Antonio, which they did in 1987. Then five years ago in the middle of the night the phone rang. It was QC. He had moved back to China and was acting as a consultant for Chinese developers building new towns in China. He had been asked to recommend a Western architect with a provable background in sustainable design who would be willing to come to China, work on large-scale master plans and perhaps some of the architecture as well.

Since that call, Blonkvist has been to China 35 times spending more than 400 days there. One referral led to another and eventually they struck up a strong relationship with Arup, one of the largest engineering firms in the world, which was involved in the Olympics Water Tube and Bird's Nest and eventually had seven offices in China.

Blonkvist said when he first went to China he was shocked to see an attitude where people were not so much interested in their own history and culture as they were in the new, the innovative, bold, flashy and glitzy. "They were more about trying to show the world that they were up to speed with the 21st century," he said.

Recently he has seen a transition. "Most of the people we work with really love and appreciate their history and their culture and they're afraid of the new young people trying to destroy it. They want to hold on to it. They want to build on it. They want to try and find a way to graft the old and the new in together without losing their history and culture," he said.

Overland now has more than a dozen projects underway in China representing about 20 percent of their workload.

After a year's work following Mayor Zhu's visit to San Antonio, Overland Partners presented a two-inch-thick, 11-by-17 book to Zhu detailing a master plan and guidelines for the Minor Qinhuai river walk over next 10 to 15 years. In the early fall, it was adopted by Yangzhou's planning department, city fathers and the mayor.

"One of the things we have done is tried to encourage them to respect and honor their history and tradition and to bring it back where appropriate, fix it up where appropriate and then where it's not appropriate build new facilities where new larger groups of people from around the world - as this is becoming a major tourist destination - will expect to have a certain level of quality Western comforts," Blonkvist said.

"So it's an opportunity for us in the West to come back, do the research and give them back their story, give them back the history that they had forgotten," he said.

Contact the writer at chrisdavis@chinadailyusa.com.

|

The San Antonio River Walk impressed the mayor of Yangzhou so much that he wanted a neglected waterway and neighborhood in his city to undergo a similar transformation. Provided to China Daily |

|

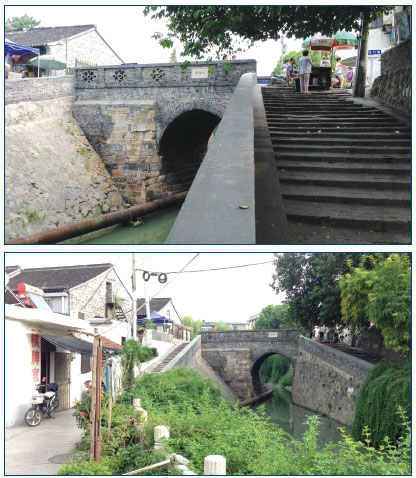

For centuries a vibrant cultural gathering place, the Minor Qinhuai River in Yangzhou has fallen to neglect. A plan has been adopted to bring it back to life. Provided to China Daily |

(China Daily USA 10/31/2014 page20)

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

China pledges financial aid to Afghanistan

Consensus sought with US on governance of Internet

US experts hope China joins trade partnership

WB report ranks China on business-friendly rules

China to join pro football wars

Mixed bag for China as US Fed ends QE stimulus

Apple's Tim Cook says 'proud to be gay'

Conference conducive to building consensus on Afghanistan

US Weekly

|

|