Visiting life and death among sheep

Updated: 2015-05-15 11:17

By Erik Nilsson and Cui Jia(China Daily USA)

|

||||||||

|

|

Huan Sezdehan and his 22-year-old son, Nursuntan Huan, tie a sheep to a motorcycle to transport it over the grassland to their spring pasture for slaughter. |

We followed death to the pasture.

This sacrificial lamb was killed to honor us.

We came late. The decapitation arrived before we did.

We'd returned from chasing newborn livestock with an 8-year-old ethnic Kazakh nomad beneath snowcapped mountains to watch his grandfather, Huan Sezdehan, sawing the hide from a beheaded sheep dangling by its back legs.

Its unblinking face gazed at us from the ground, next to a vat frothing with blood - the byproduct of halal butchering.

Huan Sezdehan's 8-year-old grandson Nurhanat Yergayit was stabbing the air with a disembodied hoof.

The boy later charred skewered chunks of sheep over the family's portable stove. Most of the mutton was roasted outside and served on a sheet on the floor.

Nomads don't lug tables around. Understandably.

We'd insisted against Huan Sezdehan's family slaughtering the sheep. Still, he and his 22-year-old son, Nursuntan Huan, cornered the creature, lashed it to his motorcycle and zipped out of sight across the prairie.

A sheep is worth about $160 - a sixth of the household's annual income. In the end, the creature bleated louder than our protests.

That's the exalting hospitality of the nomadic Kazakhs in the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region's Ili prefecture's Zhaosu county.

The boy playfully swished the disembodied hoof through the air like a wand, squished gobs of meat between his fingers and gnawed at the pelt with a pair of pliers while his father carved up the carcass. I thought about the herders' relationship with food and the animals that provide it, that are it.

I've rarely seen my food breathe. They rarely don't see it breathe.

Ili's nomads' lives revolve around their livestock.

Zhaosu's children start riding horses at age 5.

The typically scattered rovers congregate on isolated knolls on weekends to hold horse races. Only children aged 8 to 12 compete. Their nimbleness injects speed.

We watched a 12-year-old's steed eject him mid-race. He got up wiping oozing blood from his nose and lip onto his sleeve.

"It's fine," he said. "It happens all the time."

While his nose dripped crimson into his split lip, his only complaint was slight muscle pain elsewhere.

He pointed out that boys not only learn how to ride but also how to fall.

A winner of that day's race explained that parents check on the horse first if an accident happens when a child is riding.

The herders care more for sick sheep than healthy human family members and mourn flocks' miscarriages.

Ili is a place where livestock roam seasonal lanes on certain roads and bridges.

Its epic migration of tens of thousands of animals and thousands of people from winter to spring pastures is peak season for traffic police.

That said, the prefecture's congestion is more likely to come from hooves than wheels at any time of year.

I photographed a policeman smooching with a premature lamb on the lips as he stretched out on the grassland. (The critter initiated.)

Relationships with livestock change after they're beheaded.

Kazakh nomads have for millennia passed summers playingbuzkashi- basically polo with a decapitated sheep carcass.

Two teams of horseback riders line up on either side of a field and - at the word "go!" - explode forward at lightning speed and a thunder of hooves to grab the roughly 30-kilogram carcass to hurl it into a goal.

Once the carcass is seized, others aggressively claw to try and snatch it away. It's a mosh pit of grabbing and jabbing horses and hands.

Clans take turns slaughtering sheep and often stuff hides rather than play with the full corpse, to share and cut costs. But these are torn to tatters after a few sessions.

Our lunch the day before was of horse intestines with 76-year-old Hasan Wormanbek, one of about 100 men in Zhaosu's Sarkuobu village who hunt with golden eagles.

Two of the raptors working together can kill wolves, he says. Otherwise, they catch foxes or rabbits.

The raptors eat the bunnies. Local beliefs forbid humans from dining on hares.

His family wears the fox pelts. His grandson's hat is from one killed by an eagle. The birds crack their spines by yanking the canines' skulls up toward their tails.

Wormanbek explains this while stroking a stuffed fox with button eyes he made to train his birds. No inkling of irony seems to shine through.

The cute critter is cloth aside from the real tail. It looks more like a child's plaything than an instrument to teach predators how to deliver death from above.

Wormanbek tows it behind a horse with a meat chunk slung in a noose dragging from its neck to condition the birds to associate the sight with food.

He says the wintertime mountainside hunting sessions keep him spry.

Our time with the Kazakh nomads made me wonder anew what they know that we don't.

"We're fit because we do manual labor," Sezdehan says.

Herders eat natural food they produce. They drink from streams of melted mountain snow they don't need to boil, he explains.

"City people get their food from stores and sometimes sleep late because they can be lazy," Sezdehan says.

"They spend money in fancy stores. We don't earn much. But we save a lot. It's easier on the grassland. There's nowhere to spend."

Zhaosu's inhabitants navigate a world according to a compass upon which nature is true north.

I thought of the sheep we were eating. The one I saw breathing.

Our hosts are used to knowing what they eat - to the extent of recalling the personality a meal had before it ended up on their plates.

Life lessons come from that death on that pasture.

It nourished our minds and souls beyond our bellies and bodies.

Contact the writers througherik_nilsson@chinadaily.com.cn

Across America over the week (from May 8 to 14)

Across America over the week (from May 8 to 14)

Premier Li holds welcoming ceremony for Indian PM Modi

Premier Li holds welcoming ceremony for Indian PM Modi

Saved by a sunroof

Saved by a sunroof

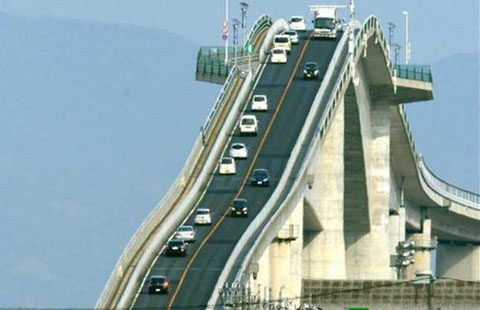

Unusual but true: Japan's bridge a nightmare for drivers

Unusual but true: Japan's bridge a nightmare for drivers

A look into Shenzhen smart watch assembly line

A look into Shenzhen smart watch assembly line

Cannes Film Festival unrolls star-studded red carpet

Cannes Film Festival unrolls star-studded red carpet

Amazing artworks in supermarkets

Amazing artworks in supermarkets

Top 10 venture investors in the world

Top 10 venture investors in the world

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Premier Li says talks with Modi 'meet expectations'

A bilateral treaty's potential praised

PBOC confirms debt-swap plan

US and Cuba to hold another round of talks

US would consider military force to defend Gulf nations: Obama

Xi to give Modi a hometown welcome

Aviation, railway top Li's agenda for Latin America

Cui rebuffs US stance on

S. China Sea

US Weekly

|

|