In education we trust

Updated: 2011-09-23 09:12

By Tan Yingzi (China Daily)

|

|||||||||

|

|

US diplomat says education is the key to building strong ties with her country

Do the Chinese people really know more about America than Americans know about China?

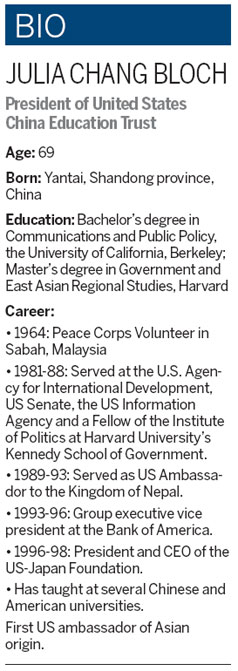

"Chinese people always say so, but it is only true to some point," says Ambassador Julia Chang Bloch, President of US-China Education Trust (USCET), in an interview with China Daily in her office on K Street in Washington, DC.

Compared to the American general public, ordinary Chinese people know more about America, she explains. However, there is a twist.

"American experts on China know more about China than Chinese experts know about America. And Chinese people don't understand American domestic politics."

That is why the accomplished Chinese-American diplomat envisioned education as the key to building mutual understanding between the United States and China when she founded USCET in 1998.

USCET is one of the few organizations involved in US-China relations that offer Chinese educators and students a chance to learn about American society and values.

Its highlight programs include the American Studies Network (ASN) and American Governance.

USCET also supports President Barack Obama's "100,000 Strong" Initiative and provides grants to American universities to encourage students to study in China.

Born in Yantai, Shandong province, Ambassador Bloch has a beautiful Chinese name: Zhang Zhixiang, which means fragrance of the Zhang family.

Her father Chang Fuyun was the first Chinese graduate from Harvard Law School in 1917 and one of republican China's most respected government officials.

Maybe because of the family education from her mother, a lady from cosmopolitan Shanghai, Bloch has a very good taste in fashion and always looks classic and graceful with her signature bob haircut.

She left China with her family at the age of nine in 1951 and settled in San Francisco. The little girl immediately took to the carefree life of the West Coast and thrived in her new country.

She earned a bachelor's degree in Communications and Public Policy from the University of California, Berkeley, and a master's in government and east Asian regional studies from Harvard.

After working in the Senate and other civil service positions, she became the first Asian-American to serve as a US ambassador (Nepal, 1989-93). Then she moved to the corporate sector to become the group executive vice-president at Bank of America. In 1996, she shifted to philanthropy, serving as president and CEO of the US-Japan Foundation.

"In all of my professional life, I have not been able to do anything on China until in 1998 when Beida (Peking University) invited me to teach there," she says.

China's top university asked the ambassador to help it revitalize its American Studies center and she became the executive vice-chairman of the center. "In 1998, China was opening and growing, so I wanted the opportunity to see for myself what China was like today and to make up (for) many years' (of) no contact."

Bloch was impressed by the smart and diligent students at Beida as well as the transformation in China.

Her first trip back to China was in 1977 on the first delegation of the American Council of Young Political Leaders at a time when the tension between the two countries began to thaw. The delegation was invited by the government to tour China and Bloch was the only Chinese-American. "It was earth-shattering. China was closed to Americans until about then," she recalls. "I will never forget that the street leading up to Tian'anmen Square was completely full of bicycles, nothing but bicycles."

She and her husband Stuart Marshall Bloch stayed at Peking Hotel, the only hotel open to non-Chinese, and "you could hear the bells (of the bicycles) in the room."

"When we arrived at the airport, it was dark without electricity, and when we got on the airplanes, they used to put on a wooden block to stop the wheel."

Starting from lecturing at Beida, Bloch has been devoted to developing the local capacity of American studies on Chinese campuses, which she believes can be more sustainable than by hiring American teachers. So far, USCET's American Studies Network is working with about 50 academic institutions in China and it also holds an annual meeting for members to exchange ideas and experiences in teaching about America.

This month, USCET will partner with Beijing University of Foreign Studies to carry out a faculty training program which aims to strengthen the knowledge and skills of Chinese professors who teach American Studies.

In China, the Ministry of Education requires that all the universities and colleges that provide English language majors must teach American Studies, which means almost every higher education institution in China teaches about America.

"American Studies is quite popular on Chinese campuses, but their quality varies and it is still developing," she says.

She finds that China's American Studies is strong in instructing about US-China relations, or the political side, but inadequate in social and cultural areas.

"You cannot understand US-China relations if you don't really understand America," she says.

Therefore, USCET's earliest initiative in China, the Congressional Practicum, has expanded to include elections seminars, training sessions and annual lectures that build knowledge among Chinese professionals, officials and students about the workings of the US legislative and political process via case study, hands-on training and interactive exchanges among US and Chinese experts.

There is one subject that Chinese experts on American studies are "head and shoulders above" their American counterparts: language.

"Even our top American experts on China, most of them don't really know Chinese that well. They rely on research assistants," she says. "That's a real problem, but it's getting better."

Language is also the biggest hurdle for the 69-year-old ambassador, whose Chinese, as she says, remains at the level of a nine-year-old girl.

"My greatest regret is I forgot my Chinese. If I were a young girl, I will study Chinese again."

(China Daily 09/23/2011 page20)