Keepers of the flame

Updated: 2013-10-17 07:13

By Li Yang (China Daily)

|

||||||||

Ethnic medicine is fast disappearing in China. Li Yang visits Nadui village in the Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region, to find out more about medical tradition.

Nadui village in Lipu county in the Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region is one of the few Yao villages left in China where ethnic medical traditions are still practiced.

The village, founded between 1862 and 1874, is surrounded by the Nadui Mountains to its east, west and north, and is home to about 100 families. It grew as people from neighboring regions came to it, fleeing from wars since the late Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). Today it is home to 302 villagers from four ethnic groups, most of them ethnic Yao people.

Almost all the older people in the village are masters of Yao medicine, which the Yao people developed over their long history of mountain life.

Yao doctors think there is a delicate balance not only in human bodies, but also between human bodies and the natural environment. Once the balance is disturbed by internal or external factors, they fall ill.

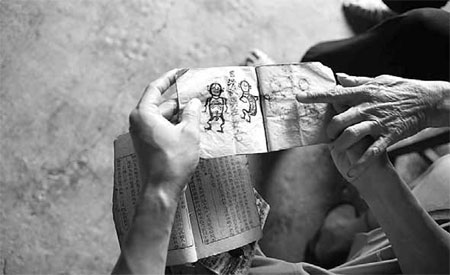

Yao people do not have their own written language. Yao medicine and medical skills are passed down through generations orally and via picture books.

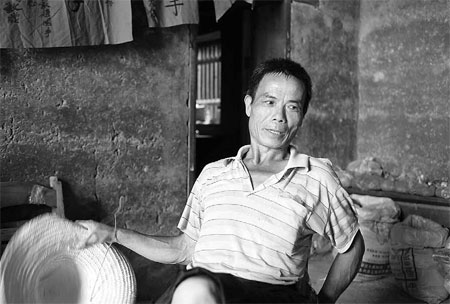

Zhao Ruming, 68, and 55-year-old Feng Jinding are the two most famous Yao doctors in the village. The inside walls of their neighboring two-story buildings are covered with banners of various shapes gifted by patients from across the country. Some of the red banners have already faded to white.

Li Chenglan complained her husband Zhao had gone into the mountains to collect herbal medicines without telling her again. Mobile phones do not work because of the poor signal.

"Sometimes he stays in the mountains for several days. He is obsessed with the medicines," sighs Li, who married Zhao in 1967 and has three sons and one daughter.

"None of my kids are interested in medicine as much as their father. I am afraid the family tradition will disappear from this generation."

Yao doctors treat their illnesses on their own. According to Li, her husband has been bitten by poisonous snakes three times when he was in the mountains. "He managed to treat himself and walk out of the mountains safely."

Yao doctors diagnose by looking, listening, questioning and feeling the pulse of the patients, very much like in mainstream traditional Chinese medicine.

Nails, palms, tongue, ears, nose, eyes, face, urine and excrement are supposed to be connected with the internal organs and are important indicators of potential symptoms, according to Yao doctors.

They use needles, animal bones, eggs, wormwood and cupping jars to massage or scrape parts of the patients' bodies as a treatment.

Fire smoke from burning certain herbs and bath water boiled with certain herbal medicines are both indispensable external treatment materials.

The wet and dim hall of Zhao Ruming's house, surrounded by cob walls, is the guest room as well as a village clinic. An old table in the corner, rumored to have been made in the Qing Dynasty, groans under the weight of dozens of plastic bags and bottles, which were arranged in neat order. Under the table are several large bags of raw materials for herbal medicines.

"I can treat some simple diseases as well," says Li proudly. "The most common medicines used by Yao doctors are for detoxification or to treat inflammation, traumatic injuries, skin diseases, arthropathy, gynopathy and venomous snake bites. In fact, almost all Yao people here know how to deal with the common ailments."

Besides the banners gifted by the patients, a portrait of Chairman Mao and a hierogram of Yao people drawn by Zhao himself are hung on the wall. His wife explains they are there to expel evil.

Countless patients have been treated in this hall, first by Zhao's father Zhao Zhiwen who passed the skills and knowledge on to him.

Yao doctors never ask their patients to pay for treatments. Many of the cases are cured with the help of Zhao and the other Yao doctors for free.

Zhao Demao, the third son of Zhao Ruming, says: "Healing the wounded and rescuing the dying for free is a central part of Yao medicine."

He became a farmer in the village after leaving the army several years ago. He often leafs through the five ancient medicine books left by his great-grandfather.

"I know these books are valuable and I am obliged to inherit the family tradition as the only son working at home. I just need some time," Zhao Demao says. "But who will I treat? The village will become empty in the future."

Zhao's medical skills do not make a big difference to his family's economic condition.

"I don't blame him and I understand it very well," says Li Chenglan. "The happiest thing is to see lives rescued or pain eased, but not the money."

The first time money ruined the peaceful life in the village, according to Li, was in the late 1950s and early 1960s, when local communes purchased bamboo and tung wood in large quantities from the villagers. The bamboo and tung forests were almost destroyed in a few years.

Since the 1990s, Zhao Ruming has often been invited to treat patients in other cities. The fact that he does not ask for money from the patients makes him a ridiculous figure to the doctors working there.

When he worked in the cities he always longed to return to the mountains. He was not accustomed to the air, noise and the people in the city, says Li.

"The religion of Yao people teaches us to add happiness to our future life by helping others as much as possible in this life. Money is irrelevant to real happiness."

Because of the lack of water and soil, the villagers live on corn, cedars, moso bamboo, teas and tung trees. They trade tea, bamboo products and tung oil with the outside world for their necessities. Most left-behind old people in Nadui still lead a hand-to-mouth existence.

Feng Jinding says: "Doctor Zhao is my teacher and model in terms of expertise and morality. He has never stopped pursuing new medical knowledge according to the changes of new illnesses. The Yao medicine and medical skills are not dead traditions but a live and evolving skill."

Over hundreds of years of evolution, the Yao people have mastered more than 1,000 kinds of clinical medicines from 104 basic raw materials of herbal medicines, animals and insects, which are classified into two categories of the strong for small injuries or illnesses and the soft for some serious illnesses such as hepatitis, nephritis, lupus erythematosus, rheumatism and even cancer.

Each Yao doctor has his or her own recipes from the 104 basic raw materials. They pick and process herbal medicines themselves and treat patients independently.

Feng believes Yao medicine does not conflict with Western medicine. "Contrarily, different medical schools should draw lessons from each other to benefit the people," he says. "We live on the mountains and the mountains help to keep us healthy. The doctors' job is not to solve troubles but to teach people how to prevent troubles and live with nature."

Contact the writer at liyang@chinadaily.com.cn.

Huo Yan contributed to the story.

|

Zhao Ruming, 68, is an inheritor of Yao medicine in the mountainous village Nadui in Lipu, in the Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region. Photos by Huo Yan / China Daily |

|

A picture book about Yao medicine and medical skills, which has been passed down through generations, is a treasure of Zhao Ruming's family. |

(China Daily 10/17/2013 page20)

Victoria Beckham S/S 2014 presented during NYFW

Victoria Beckham S/S 2014 presented during NYFW

'Despicable' minions upset Depp's 'Lone Ranger' at box office

'Despicable' minions upset Depp's 'Lone Ranger' at box office

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

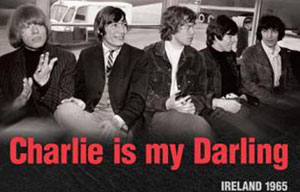

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Facebook goes fishing in China

Michigan auto czar leading trade trip to China

Deal reached to avoid US default and open govt

Yuan gains the most in 20 years

Tibet avalanche claims 4

First interprovince subway route opens

US expert finds job 'rewarding'

Trending news across China on Oct 17

US Weekly

|

|