Satellite of love

Updated: 2013-12-03 09:31

By Raymond Zhou (China Daily)

|

||||||||

To most Chinese, the moon will not drive you crazy. Rather, it is the realization, buttressed with high-resolution photos taken by satellites and rovers, that the moonscape looks just like a desert, that is an absolute wet blanket on the romanticism associated with the Earth's natural satellite.

But then, we have learned that science, while capable of unraveling ancient mysteries, should be kept at a distance when we need to conjure up the perfect atmosphere for longing.

The moon featured so prominently in classical Chinese literature that a treasure trove of terms was spawned for description and reference: The Jade Rabbit, the Ice Wheel, the Jade Bow, the Jade Plate, the Ice Mirror, the Jade Toad, the Night Light, the Grand Chill Palace, to name just a few. Most of these terms sprout from a single source - the legend of Hou Yi and Chang'e, who do not so much represent the Sun and the Moon as form the core of traditional Chinese interpretations of celestial bodies.

According to the legend, Hou Yi was a master archer who shot down nine suns to prevent the earth from being scorched. He left one last sun in the sky so people and their crops could get a healthy dose of sunlight. Hou entrusted a packet of immortality pills to the care of his beautiful wife Chang'e, but while he was away on a hunting trip, a burglar came to rob them. Unable to defeat the bad guy, Chang'e downed the pills.

As she transformed into a fairy, her body became so light that she floated upward. That night, having lost his wife, Hou Yi noticed the moon was extremely bright and believed it must be Chang'e pining for him. From that day on, Hou Yi appeased his yearning by praying to the moon. People soon followed his lead by praying for peace and bliss for their loved ones.

One subplot, with numerous variations, features a man called Wu Gang, who was sentenced to cut down a giant laurel tree in front of the Grand Chill Palace on the Moon. Every time he hacked into the trunk, the cut healed instantly. This tantalizing game went on forever, signaling the futility of Wu's effort.

The moon as a common object of attention, romantic or otherwise, has inspired a plethora of immortal lines in the Chinese language. Almost every Chinese poet has devoted at least one ode to it. Perhaps the greatest flowed from the brushes of illustrious names. Li Bai's Night Thoughts is familiar to every Chinese schoolchild: "I wake, and moonbeams play around my bed / Glittering like hoar-frost to my wandering eyes / Up towards the glorious moon I raise my head / Then lay me down - and thoughts of home arise."

In another poem, Li writes of a drunken ecstasy in which he toasts the moon and engages in a little pas de trois involving the moon, himself and his shadow in the moonlit night.

During the Song Dynasty (960-1279), Su Shi employed a similar metaphor of dancing and almost cavorting with the moonbeams, before continuing: "Men have sorrow and joy, they part and meet again / The moon is bright or dim and she may wax or wane / There has been nothing perfect since the olden days / So let us wish that man / Will live as long as he can / Though miles apart, we'll share the beauty she displays."

Moonbeams may be pale and icy, but they embody the serene allure of femininity in contrast to the sun's burning machismo. Du Fu best captures that slightly amorous feeling when he describes his wife's "white jade arm" glistening in the moonlight. One can almost imagine a gauzy image with perfect chiaroscuro, something out of a 1930's Hollywood tearjerker with the couple on the deck of a ship and the moonlight dancing on the ocean waves.

The moon of Western culture, a symbol of inconstancy or madness, must be envious of her stature in China. Here, the moon is not to be conquered; she is to be embraced with tenderness. Wax or wane, during the Mid-Autumn Festival, or indeed any other night, the moon softens our hearts and makes us believe in the magic of love.

Simulated archaeology takes you back in time

Simulated archaeology takes you back in time

Thai PM calls for talks, protest leader defiant

Thai PM calls for talks, protest leader defiant

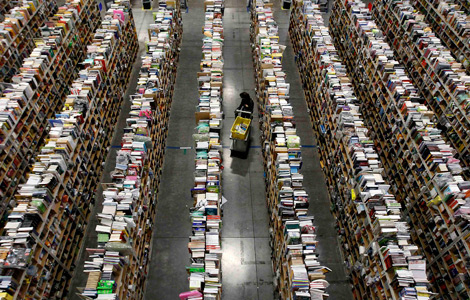

'Cyber Monday' sales set to hit record

'Cyber Monday' sales set to hit record

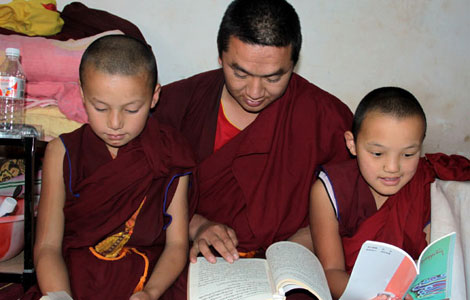

Tapping the power of youth volunteers

Tapping the power of youth volunteers

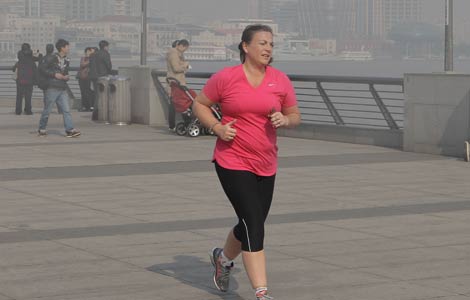

Shanghai braces for second day of severe pollution

Shanghai braces for second day of severe pollution

Private hospitals face challenges

Private hospitals face challenges

Chinese premier meets Britain's Cameron

Chinese premier meets Britain's Cameron

Washington's panda named Bao Bao

Washington's panda named Bao Bao

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Staggered flu shot plan best for China: study

Online shopping changing retail world

House hunting the world in Chinese

Chinese credit agency forecasts future US downgrade

China-UK collaboration is about time: President Xi

Biden's Asia trip under pressure

FTZ OKs offshore accounts

Amazon testing delivery with drones

US Weekly

|

|