Californian brings savvy, innovation to language class

Updated: 2012-07-20 11:33

By Chen Jia in San Francisco (China Daily)

|

||||||||

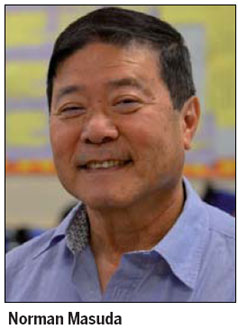

Norman Masuda appreciates the complexity of Chinese but empathizes with those who struggle with the language.

Like them, the Japanese-American teacher in California is not a native speaker.

On a recent Wednesday morning, the 70-year-old addressed his class of 20 at Palo Alto High School in simple Mandarin, aided by body language and an iPad app that uses animation.

"As a non-native speaker of Chinese, I know how to push them in adapting to a real language environment," he told China Daily after a lesson in the school's free summer course in Chinese language and culture.

The entry-level course is voluntary for the students, most of whom have had no experience with Mandarin.

As a student at the University of California, Los Angeles, over 50 years ago, Masuda took the advice of a Beijing-born instructor to pursue an interest in Chinese literature. His parents, however, wanted Masuda to study science.

"In the 1960s, Americans learned Chinese because we wanted to know more about the culture of a country behind a veil of mystery," he said.

Today, Chinese-language students are more driven by economic development and business opportunities. Attitudes about teaching Chinese have also changed since the '60s, when UCLA listed Chinese under the heading "Oriental Language".

"That was not a pleasant word and indicates historical discrimination against Chinese and Japanese. In today's United States, the term is considered derogatory," he pointed out.

After graduating from UCLA, Masuda went on to an interuniversity program for Chinese studies in Taiwan and then Stanford University the following year for graduate work in Chinese literature. After passing oral exams for his PhD, he worked on his dissertation at Japan's Kyoto University on a Fulbright fellowship. He returned to Stanford to teach Chinese before joining the faculty at Palo Alto High. Back then, the school had about 2,000 students, with just 20 enrolled in Chinese classes.

Masuda has been the lead instructor for the Palo Alto Unified School District's Startalk program since its inception six years ago. Startalk is an offshoot of a US government national-security initiative that also involves Stanford University's World Languages Project.

Chinese instruction in the US was beset by difficulties between 1980 and 1995, when many foreign-language courses fell victim to cuts in states' education budgets.

While some languages have failed to return to schools' course offerings, "Chinese survives and booms," Masuda said.

Since those dark days, Chinese teaching and learning have experienced a revival, including the opening of the first Confucius Institute in Maryland in 2005. There are now 81 Confucius Institutes in the United States, funded by China's central government and run as partnerships between Chinese and US universities. The institutes have dispatched more than 2,100 Chinese teachers to the US.

The nonprofit institutions have encouraged and challenged local teachers such as Masuda in their pedagogical approach.

"I have researched some curricula from the Chinese mainland, but most highlight the importance of grammar rather than communicative methodology," he said. "They also don't provide enough supplementary reading materials."

"As non-native speaker of Chinese, my personal study experience helps me better understand how to choose and teach using more-practical curriculum materials."

After receiving an Apple iPad for Christmas a year and a half ago, "I asked myself, 'Why not combine a popular, state-adopted Chinese curriculum with the advantages of the iPad platform?'"

The melding of tradition with high-tech seems to be working with Masuda's students, who find the classroom more open to dynamic learning, the seasoned teacher said.

Contact the writer at chenjia@chinadailyusa.com

Relief reaches isolated village

Relief reaches isolated village

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Earth Day marked around the world

Earth Day marked around the world

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|