A man apart

Updated: 2012-11-27 07:50

By Mei Jia (China Daily)

|

||||||||

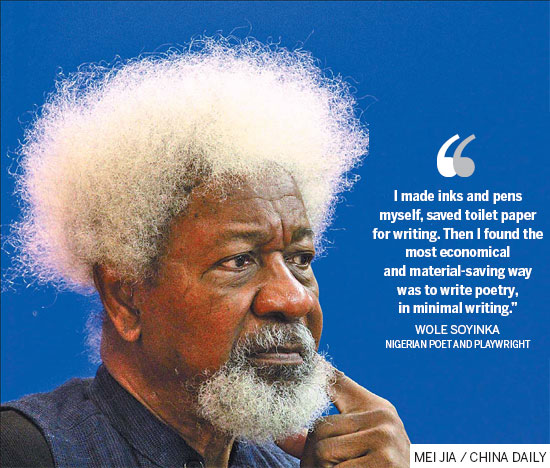

From his hair to his words, a visiting African writer inspires with his individuality, Mei Jia reports.

Upon meeting Nigerian poet and playwright Wole Soyinka, the first African to win the Nobel Prize for Literature, Chinese writer Yan Lianke is amazed by his peer's upright and treetop-shaped hairstyle. The 78-year-old laureate paid his first visit to China recently, where he found strong enthusiasm for his works from Chinese writers.

Yan praised Soyinka for being extraordinary from his hair to his works. When literary critic Chen Xiaoming also related the African's hairstyle to his writing, Soyinka joked that he felt a new theory of literary criticism is coming.

But the real story of his hair is a bitter one. Soyinka's experience of maintaining his hair in the United Kingdom has been an energizing force behind the fights of his lifetime, for national independence and for personal freedom. These themes also enrich his literary creations, inspiring Chinese writers and readers since the days his works were first translated in the early 1980s.

Soyinka says it all started when he went to a barber's in Leeds, UK, when he was studying English literature there in the 1950s.

"The barber had no experience of cutting African hair - there were not too many African faces there then," he says.

"He did my hair in a way he wanted, but not how I wanted. I was not happy, telling him he should pay me actually for giving him the rare experience," he says.

Soyinka hasn't set foot in a barber's shop since, and his hair is "nature's work", he says.

During his visit, Soyinka spoke on "Africa in Globalism's Cross-currents" at Peking University and "50 Years in Pursuit of African Renaissance" at Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. One of his masterpieces, The Lion and the Jewel, debuted in a public theater in Beijing.

Under Peking University's artistic director Joseph Graves and visiting professor Femi Osofisan, the Chinese version of the play shone with zealous performers, English dialogue and accompanying African drum beats.

The play reminds writer Xu Ze-chen, 34, of the days when he read the play in the 1990s while at university. He and his friends, he says, "were strongly touched by Soyinka's style of surreal, absurd and cynical writing".

Soyinka also makes Chinese writers and critics like Xu pay attention to Nigeria's literary tradition and strength, including Booker Prize winner Ben Okri's The Famished Road, and Orange Prize winner Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's Half of a Yellow Sun.

Soyinka says he tends to affiliate more with the bigger African cultural identity - "Africanity" as he calls it - than the Nigerian one, according to the Southern Weekly.

"Soyinka was a pioneer. He and J.P. Clark more or less laid the foundations of what we know now as modern African theater in English," says Osofisan, who is also a notable Nigerian writer.

To Osofisan, Soyinka is not only an inspiration but also a teacher who's always willing to help out.

"He is one of the best people you can know, very caring and compassionate and always full of laughter," Osofisan says.

Soyinka has long been associated with political activities that overthrew British colonialism and brought down dictators. Being imprisoned and expelled at times, he has a rich life experience that he presents in his dramas and poems.

Soyinka has also been teaching in British and US universities, including Yale, Harvard and Oxford.

"In my class of comparative literature, I expand the reading material from colonial literature to Asian literature, which includes Chinese and Japanese literary works," he says.

"Politics is one part of my writing," Soyinka says. "But political fashion changes, literature remains."

Osofisan recalls when Soyinka was in exile after the civil war he was a graduate student in Paris, at the Sorbonne. "In fact, it was in his car that I rode to Paris from London."

The battling writer had been in prison for months, with no pen or paper at hand.

"I made inks and pens myself, saved toilet paper for writing," Soyinka told the Southern Weekly.

"Then I found the most economical and material-saving way was to write poetry, in minimal writing," he says. "All the other surging ideas had to wait."

Soyinka won the Nobel in 1986 for being a writer "who in a wide cultural perspective and with poetic overtones fashions the drama of existence".

He says he noticed the huge national response after Chinese writer Mo Yan won the same prize in October.

"We had massive celebrations back in my country, too, when I won," he says. "But the prize has too much mystique."

"Of course the money of the prize is important for a poor writer like me," he says, adding he used the money to build a house as a retreat for other writers and expand his stock of wine.

Soyinka has also enjoyed interacting with Japan's Nobel laureate Kenzaburo Oe, a longtime friend. Being longtime friends, Oe applies Soyinka's characters, dialogues and images to his own works in new ways.

"It's the special way two great minds exchange," Oe's Chinese translator Xu Jinlong says.

Contact the writer at meijia@chinadaily.com.cn.

(China Daily 11/27/2012 page19)

Relief reaches isolated village

Relief reaches isolated village

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Earth Day marked around the world

Earth Day marked around the world

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|