Restoring fertility

Updated: 2012-12-05 07:52

By Erik Nilsson (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

Sheng Yuncai is one of the herders-turned-farmers who has shaken off poverty by planting congrong, a medicinal herb, in the Alxa region of Inner Mongolia. Erik Nilsson / China Daily |

Helping men perform better in bed could rejuvenate Alxa's grasslands - and make locals richer than ever. Erik Nilsson reports.

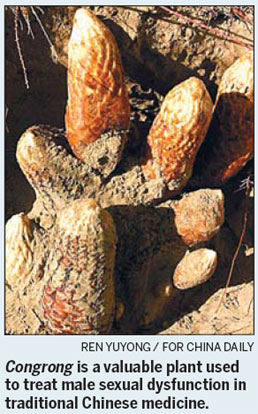

The planting of congrong - an herb infused into boozy tonics that traditional Chinese and Japanese medicines use to treat male sexual dysfunctions - has been crucial to decelerating the deserts' conquest of the Inner Mongolia autonomous region's prairies.

Congrong has been used in Chinese tonics for millennia to remedy impotence, ejaculation difficulties, groin and knee wounds, and infertility - basically, anything that could afflict a man's nether-regions. Its health benefits were documented by Shennong - the legendary herbalist, "Divine Farmer" and deified doctor from whom mythology says all Chinese descended about 5,000 years ago.

Congrong grows as a parasite on the roots of suosuo, a plant used to reverse desertification.

After a decade of planting thousands of hectares of suosuo, the Tengali, Badanjilin and Lanbuhe deserts have slowed their encroachment into the Alxa grasslands in Inner Mongolia's northwest.

About 60 herdsmen-turned-farmers have planted the cash crop over the past decade through the Japanese NGO the OISCA Institute for Alaxa Ecology's suosuo project, which provides seedlings, funding and knowhow.

It's an effective tactic in a war where the government has tried everything from blasting the sand dunes with "seed storm" payloads to erecting fences to keep sheep from gobbling up the remaining prairie.

And participating locals are earning more than ever. They can make tens of thousands of yuan a year in an area where herders - and especially Alxa's more than 60,000 nomads - earn less than the average annual income of 3,000 yuan ($482).

It takes congrong three years to mature so that Alxa's farmers can sell it fresh for 200 yuan a kilogram and dried for 240 yuan.

The expansion of suosuo planting, led by OISCA, comes as herders are being ejected from the pastoralism they've practiced for centuries. Their livelihood has been starved by the disappearance of their livestock's food source and restricted by government regulations that will limit livestock next year.

Sheng Yuncai earned about 3,000 yuan a year raising sheep until the desert devoured his grassland more than a decade ago.

"Our livestock had nothing to eat," the 40-year-old ethnic Mongolian says.

"We had no idea what to do. We didn't know how we could live."

Over the last 10 years, he planted about 300 hectares of suosuo, beneath which he grows congrong.

"It's good to contribute to our environment. This was grassland for most of my life," he says, waving toward the desert that tumbles beyond the horizon.

Sheng misses the prairie days. The land around his house - a lonely structure in the wasteland - is devoid of life except for his suosuo plot. It's a green island in a yellow sea of sand.

"This isn't a local problem," Sheng says. "It's a national problem."

Actually, it's a global problem. Siberian winds propel Alxa's dust to sandblast not just Chinese cities like Beijing but even the western United States.

Suosuo is a remarkable solution, Sheng believes.

It not only has restored his land but also its congrong has increased his annual income from agriculture fivefold over the 3,000 yuan he earned raising sheep.

"My land is returning, and I earn more than we ever dreamed. Our family enjoys a better living standard than we ever expected."

Sheng sells his congrong to Mandela Co, which processes it into liquor in a partnership with Tianjin University, he says.

"This kind of farming brings more money than herding and is better work," Sheng says. "As a herder, I had to spend every waking moment lashed by icy winds. There was no choice. But suosuo doesn't require much care. I only have to tend my field four months a year."

Sheng uses his spare time to make about 4,000 yuan a month as a driver.

Wu Lankou, an ethnic Mongolian who lives down the road from Sheng, also hopes to shift from sheep ranching to suosuo and congrong planting. But Wu doesn't have enough land to support his family, he says.

He has grown half a hectare of suosuo for six years but hasn't planted congrong.

The grassland upon which his 200 sheep grazed died in the mid-'90s. And his livestock will be outlawed next year.

"We have absolutely no clue how we'll survive," he says.

"But I support the government policy. This desert must be stopped. Either way, we'll lose our sheep - through their starvation or by law. At least with the policy, the grassland might be restored."

Wu had fed his 190 sheep with food purchased outside but can't afford to do so anymore, he says.

"We're broke," he says.

"And we have no idea how to make money without herding."

OISCA program officer Su Lide explains: "Our organization has tried dozens of ways to reverse the desertification and restore the grassland, with mixed results. Our suosuo project has been the most successful. It has the advantage of improving local incomes, which is likely why herders are eager to join."

Poultry producer Wulanbatu'er, an ethnic Mongolian who raises emus and tends 24 hectares of suosuo through OISCA's projects, believes such practices can control the crisis.

"Through such innovations, we can turn the desert back into grassland," he says. "And we'll live even better than we did before the desert came."

That's not to mention the sexual benefits men outside of Alxa reap from the project - almost certainly doing so with little inkling of the land from which their congrong comes or its people.

Contact the writer at erik_nilsson@chinadaily.com.cn.

(China Daily 12/05/2012 page19)

Relief reaches isolated village

Relief reaches isolated village

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Earth Day marked around the world

Earth Day marked around the world

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|