Chasing the fading music

Updated: 2014-05-27 07:13

By Huang Zhiling (China Daily USA)

|

||||||||

One woman's passion for the songs of a remote ethnic people may save not only the Muya's music, but the language itself. Huang Zhiling reports from Chengdu.

Muya music might already be lost if Yang Hua had not given up her job as a mathematics teacher.

Yang taught in a well-known primary school in Chengdu, Sichuan province, for three years after completing her college studies. But thanks to her childhood love of music, Yang became a postgraduate student in the department of composition at the Sichuan Conservatory of Music in 2004. Two years later, she became a teacher in the department.

"I started learning how to play the accordion and the piano at 5. Passion for music has motivated me to record Muya music and introduce it to the world," says the 35-year-old in her studio on the 21st floor of a residential building in Chengdu.

The area between the Yalong and Dadu rivers in the Garze Tibet autonomous prefecture in Sichuan is called Muya and its inhabitants are the Muya people, considered a branch of Tibetans. Their land is surrounded by Tibetan-inhabited areas, but the language of the Muya and their music are different from those of Tibetans.

Researchers have diverse views on the origin of the Muya. Some think they are descendants of the Tangut ethnic group who founded Western Xia (1032-1227), a feudal kingdom at the eastern end of the ancient Silk Road. They migrated to their current base after their kingdom fell to a Mongolian invasion.

"Others believe they are aboriginal Tangut people who have lived in the Muya area since ancient times," Yang says.

With a population of some 10,000, the Muya people are scattered in Kangding, Daofu, Jiulong and Yajiang counties in Garze. Due to strong influence of the Tibetan language, many of them no longer speak, let alone sing, in their mother tongue. They have no written language.

"Thirty years ago, people in some townships in the counties spoke the Muya language. But few do so now," says Quji Jiancai, a Living Buddha in the Guwa Monastery in Kangding county.

In 2008, Bamu, a singer with the Jiuzhaigou Art Troupe in the Aba Tibetan and Qiang autonomous prefecture in Sichuan, came to record a song in Yang's studio.

At first, Yang did not pay much attention to the 20-year-old as she was dressed like every modern Chinese girl. But when she sang the Ode to Mom, Yang found the song very special as the voice was deep and low, unlike the resounding Tibetan songs.

After the recording was over, Bamu told Yang it was a folk song of the Muya people. The song told how a girl working outside her hometown misses her mom, who says jewelry does not mean anything if one is not educated, and the singer wishes her mom good health.

"It was the first time I heard the word 'Muya'," Yang says.

During the next Spring Festival, Yang reached Bamu's home village of Juli in Kangding after nine hours of travel by bus and taxi.

"I stayed for 15 days in Bamu's home and enjoyed musical and theatrical performances in the Juli Monastery," Yang says.

In late 2010, she got a grant of 30,000 yuan ($4,810) from the Ministry of Education, to fund work for the protection, inheritance and development of the Muya music and culture. The Sichuan Conservatory of Music gave her an additional 30,000 yuan.

Bamu volunteered to be Yang's interpreter, but only in winter when her performance troupe was resting. That meant navigating icy, rugged roads at the Zheduo Mountain Pass, more than 4,000 meters above sea level.

Even more difficult was finding people who would sing in the Muya language, for people there were very shy.

"When I first reached Bamu's home, a dozen people in her family except Bamu fled. Only when I was not at the dinner table, they would return furtively to see if I had finished the food," Yang says with a smile.

In the end, Yang could only record Muya music when there were performances in a public square, such as during the Spring Festival in 2011. Otherwise, even during the holiday, people were too shy to sing in front of a stranger.

Since 2011, Yang has stayed in Bamu's home each winter, traveling all over the area and recording hundreds of folk and pastoral songs.

In 2012, Yang made an album with seven folk songs of the Muya people sung by Bamu. "I dreamed of bringing Muya music out of the mountains. Now with the album, more people can listen to it," Bamu says.

In December that year, Yang and her colleagues organized a chamber concert of the Muya music in the Sichuan Conservatory of Music.

That was a first for any conservatory, according to Song Mingzhu, dean of the department of composition at the Sichuan Conservatory of Music.

To help preserve the unwritten language, Yang says, "I came up with the idea of launching an audio dictionary. I started with the Chinese words whose pronunciation begins with 'a' in pinyin. I have recorded all the words from A to Z."

Contact the writer at huangzhiling@chinadaily.com.cn

|

Muya singer Bamu performs on the square of the Juli Monastery in Kangding, the Garze Tibet autonomous prefecture in Sichuan province. Provided to China Daily |

|

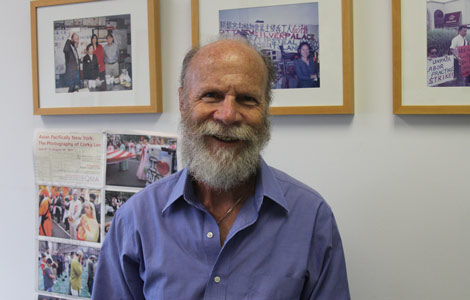

Yang Hua, a researcher on Muya music, at her studio in Chengdu. Huang Zhiling / China Daily |

(China Daily USA 05/27/2014 page8)

'Face-Bikini' swimwear trend sweeps East China

'Face-Bikini' swimwear trend sweeps East China

Iraqi pilgrims gather to honor Muslim saint

Iraqi pilgrims gather to honor Muslim saint

Shanghai crowds flock to China, Russia battleships

Shanghai crowds flock to China, Russia battleships

Documenting reaching fame the hard way

Documenting reaching fame the hard way

US president pays surprise visit to Afghanistan

US president pays surprise visit to Afghanistan

Forum discusses strategies to realize Africa's promise

Forum discusses strategies to realize Africa's promise

South America is prime market for Chinese automakers

South America is prime market for Chinese automakers

Brazil names winners for 'Bridge' finals

Brazil names winners for 'Bridge' finals

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

US urged to explain cyberspace spying

Yao Ming mulls Clippers bid

Beijing subways to get 4G coverage

Xinjiang's stability a top priority

More efforts against arms smuggling

Anti-terror campaign launched

China lifts shellfish ban

Children from China enroll in US summer academic camps

US Weekly

|

|