|

|

A clerk counts yuan bills at a bank in Huaibei, East China's Anhui province. [Photo/IC]

|

A spate of recent commentary has been warning of the vertiginous rise in China's debt, which jumped from 148 percent of GDP in 2007 to 249 percent at the end of the third quarter of 2015. Many are anxiously pointing out that China's debt is now comparable to that of the European Union (270 percent of GDP) and the United States (248 percent of GDP). Are they right to worry?

To some extent, they are. But while observers' concerns are not entirely baseless, it is far too early to sound the systemic-risk alarm. For starters, China has a very high savings rate-above 45 percent over the last decade, much higher than in the advanced economies-which enables it to sustain higher debt levels.

Moreover, China's banking system remains the primary channel for the deployment of the household sector's savings, meaning that those savings fund corporate investment through bank lending, rather than equity financing (which accounts for only about 5 percent of net investment). Indeed, the sharp acceleration in the debt-to-GDP ratio is partly attributable to the relative underdevelopment of China's capital market.

Once these factors are taken into account, China's overall debt levels do not seem abnormally high. While debt might be a problem for Chinese companies with excess capacity and low productivity, companies in fast-growing, productive sectors and regions may not be in too much trouble. More generally, China has made recent progress in boosting labor productivity, encouraging technological innovation, and improving service quality in key urban areas, despite severe financial repression and inadequate access to funding by small and medium-sized private enterprises.

People in shock after Florida nightclub shooting

People in shock after Florida nightclub shooting

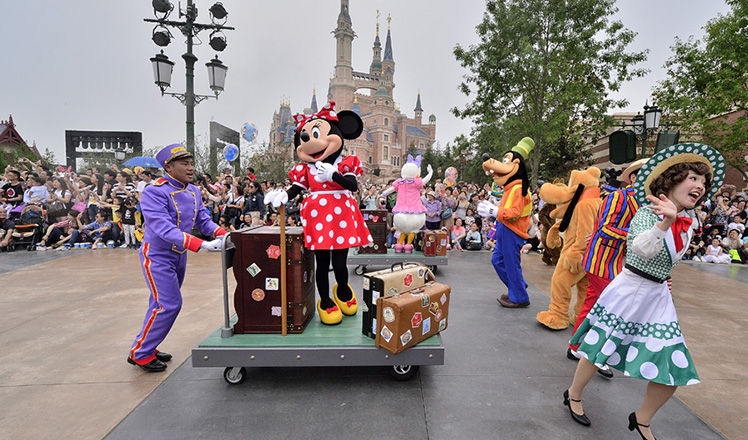

Shanghai Disneyland all set for official opening on Thursday

Shanghai Disneyland all set for official opening on Thursday

British pageantry on parade for Queen's official birthday

British pageantry on parade for Queen's official birthday

Carrying bricks to selling carrots: Life of child laborers

Carrying bricks to selling carrots: Life of child laborers

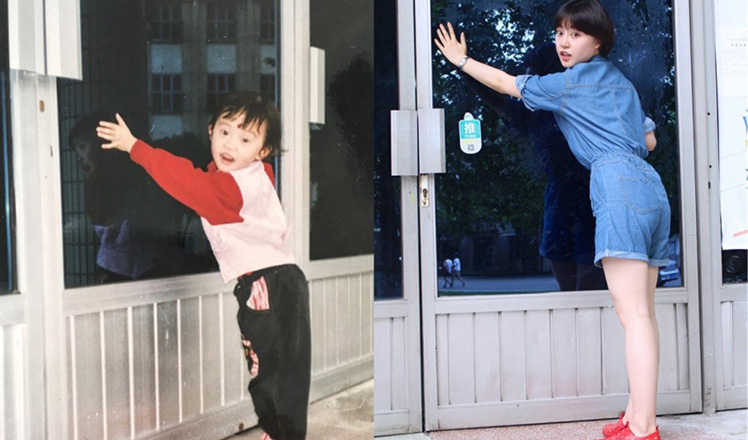

Graduate revisits same university spot 19 years later

Graduate revisits same university spot 19 years later

Euro powers land in France for UEFA EURO 2016

Euro powers land in France for UEFA EURO 2016

The most unusualgaokao candidates in 2016

The most unusualgaokao candidates in 2016

Elderly man carries on 1000-year old dragon boat craft

Elderly man carries on 1000-year old dragon boat craft