Larger than life

Updated: 2015-09-19 03:52

By Xu Xiaomin in Shanghai

|

||||||||

|

|

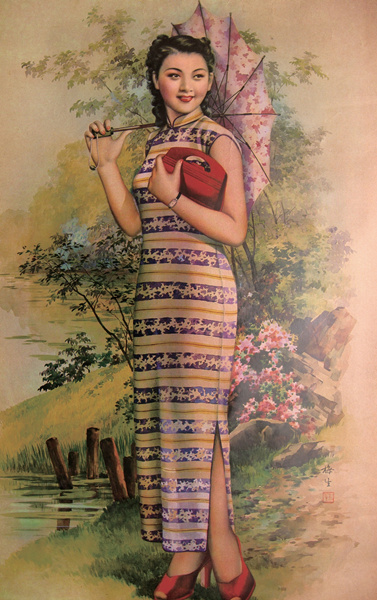

Timeless beauty: Jin Meisheng’s illustrations of the "Shanghai lady". PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY |

Almost always clad in a skin-tight qipao, or cheongsam, this woman was once a ubiquitous figure in Shanghai. She wore different faces and had no name, but she would captivate the world with a smile that was laden with oriental seduction. Although even the most gorgeous of individuals will eventually fall prey to the effects of time and wither with age, this woman has seemingly defied this logic; her beauty forever immortalized, quite literally, above time.

She is none other than Shanghai’s iconic calendar girl.

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the birth of calendar painting, an art form which can still be found in old-fashioned restaurants, movies about old Shanghai and art galleries. It was once such a famous product of Shanghai that many people have even likened the art to being “Shanghai’s name card”.

“Calendar painting is a popular art form in local society that reflects Shanghainese style. It may just be a painting, but it also evokes a sense of fascination in people about the city,” said Dai Zhiqi, an art school teacher and a fan of calendar painting.

During a time when women in Shanghai were conservatively dressed in black or navy blue attire, the curves of these painted beauties on the calendars seemingly made up for the shortage of feminine charm in the society. Such calendars were deemed to be a necessary ornament in Chinese families and were usually kept in bronze frames for protection as these calendars would be hung on the wall for at least a year.

|

|

Timeless beauty: Jin Meisheng’s illustrations of the "Shanghai lady". PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY |

The origins of calendar painting

Calendar painting actually started off as a form of product advertising. When Shanghai became a treaty port after the Qing government lost the First and Second Opium War to foreign armies, traders from abroad started coming to the city to sell Western products such as soap, cigarettes and medicine.

In order to attract the locals to buy their products, the foreigners resorted to using classical paintings or painted advertisements by Western artists to promote their wares. But that failed miserably, as most of the locals did not understand the foreign culture. As a result, these traders turned to local artists for help instead.

“They took inspiration from traditional Chinese New Year paintings and started to invite local artists to do advertising painting. This gradually gave birth to the Shanghai-style calendar art,” said Chen Qi, deputy director of Shanghai Art Association, during an calendar art seminar held in Shanghai earlier this year.

Apart from beautiful women, people could also find children and home decorations in these calendars, which soon became the representation of what people should strive to achieve in life. The product’s image and slogan were usually printed in a corner of the painting.

“It was a kind of advertising art. In the beginning, the advertiser invited Chinese artists to create their own designs, most of which were traditional Chinese subjects such as a popular opera scenario or an ink painting of landscapes,” Chen added. “Gradually, as Western culture started to exert a bigger influence on local society, modern women became an overwhelmingly popular subject.”

For a long time, exposing too much skin was considered to be taboo in Chinese culture, but calendar paintings shifted societal perception and made revealing attire acceptable. These paintings always depicted a modern Chinese lady; the antithesis of the traditional woman who would never expose her teeth when she smiled. Besides body-hugging cheongsams, calendar women could also be found in sexy sports shorts, modern Western dresses and even swimming suits, and they would be participating in activities such as riding a bicycle or playing tennis. Some would even be depicted as a confident, sophisticated individual smoking in a café.

“One reason the calendar lady became so successful was that it offered everyone the idea of the perfect woman, which was more or less a shortage in the spiritual Chinese society at that time,” said Wang Bangxiong, professor from Shanghai Theatre Academy.

Because of the popularity of these calendars, shrewd businessmen often bundled them with their products to attract more sales. The Nanyang Brothers Tobacco Company, which was set up in 1905 and became a major tobacco producer in Shanghai, relied heavily on these calendars to boost their sales. They even had an annual budget set aside for calendar painting.

Jin the painter

Due to its massive demand, calendar painting quickly developed in Shanghai in the 1930s and some artists started setting up their own studios to capitalize on the boom. The profession was a lucrative one, too — during a time when the average monthly income of a middle school teacher was between 50 and 140 yuan, a painting by a well-known artist could fetch as much as 500 yuan. But creating top notch work was time consuming as well, and a piece could take as long as a month to complete.

Some of those who could command such fees were artists like Jin Meisheng (1902 -1989). Jin started learning about water color painting in 1919 from a master craftsman named Xu Yongqing and he gradually developed interests in calendar painting after working in a publication house. He had five sons, but Jin Peigeng was the only one who followed in his father’s footsteps. They became the only father and son duo in Shanghai specializing in calendar painting.

“Ladies in Four Seasons” was one of the most popular art works by Jin, whose many other creations had print runs of over 1 million. Peigeng revealed that though his father had painted countless portraits of beautiful women, none of them were actually based on a real person.

“My father didn’t invite models to his studio as society was not that open-minded. Instead, he got his inspiration from magazines, or based his paintings on his imagination,” Peigeng said. “The ladies who were created from his imagination were the best-looking ones.”

One of the special skills that the Jins used in their work is called stumping, a combination of traditional Chinese and Western painting techniques. They would first sketch the subject using a pencil before using a modified wool brush to carefully rub stumping chalk powder on the paper, creating a shadow effect that makes the illustration look three dimensional, an element that is absent from traditional Chinese paintings. The artist would then use watercolor to add vibrancy and realism to the work.

“Good artists only used imported materials and tools like paper, colors, powder and painting brushes,” Peigeng said. “Only the imported colors would show a very decent and bright red or blue.”

|

|

Jin Peigeng, son of Jin Meisheng, talks about special techniques in calendar painting. GAO ERQIANG / CHINA DAILY |

The demise of calendar painting

Apart from Shanghai, calendar paintings were also very popular in Southeast Asian countries and Europe. Jiang Xianhui, editor of the book One Century of Shanghai Calendar Painting, noted that many traders would purchase hundreds of paintings in Shanghai before returning to their home countries.

Advertising materials were on the decline following the liberation of China in 1949 as the government launched a reform over the commercial advertising industry and calendar painting became a protected folk art that later evolved into an art form associated with Chinese New Year. In 1954, Shanghai established a special publication house to produce such paintings. Jin, along with other famous artists such as Xie Zhiguang and Li Mubai, were invited to set up their own studios.

As the government sought to reflect the new values of the country, illustrations of farmers and workers replaced the iconic Shanghai lady in these Chinese New Year calendars. To better understand their new subjects, studios often organized excursions so that artists can practice sketching scenes of people hard at work, such as farmers raising healthy pigs.

The craft of calendar painting took a hit in the 1960s when the political climate prevented the development of art studios. When the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) came about, calendar painting was rendered almost inexistent. The final blow to the art form came when photographic technology became popular in the 1980s.

Though calendar paintings have now become a historic artifact, the timeless beauty of those women are still etched into the minds of many people. He Xiaoliang, a Shanghai native, still vividly recalls the woman on the calendar from his childhood days in the early 1980s.

“Our old house was really dim and every piece of furniture looked a little sad in such light. The calendar that was hung in the living room was the only thing that stood out,” he recalled.

“I can still remember the woman in the calendar. She was wearing white fur and red pants. She was the prettiest woman to me at that time.”

xuxiaomin@chinadaily.com.cn

- World's oldest male panda celebrates 30th birthday

- Women's development in China contributes to global equality: white paper

- China releases full text of reform plan for ecological progress

- Upgraded combat drone is unveiled

- Villagers scoop up big profits by drying fish

- Food safety a long-term endeavor

-

From Iowa farm to White House: Look back at Xi's US visits

From Iowa farm to White House: Look back at Xi's US visits

Buses with images of 6 endangered animals of China drive in US

Buses with images of 6 endangered animals of China drive in US

Burberry Prorsum Spring/Summer 2016 collection

Burberry Prorsum Spring/Summer 2016 collection

Top 10 favorite hotel brands of rich Chinese

Top 10 favorite hotel brands of rich Chinese-

Top 15 Chinese CEOs to attend US roundtable during Xi's visit

Top 15 Chinese CEOs to attend US roundtable during Xi's visit -

House showcasing Sino-American friendship opens to visitors

House showcasing Sino-American friendship opens to visitors -

To be continued...

To be continued...

World's oldest male panda celebrates 30th birthday

World's oldest male panda celebrates 30th birthday

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Young people from US look forward to Xi's state visit: Survey

US to accept more refugees than planned

Li calls on State-owned firms to tap more global markets

Apple's iOS App Store suffers first major attack

Japan enacts new security laws to overturn postwar pacifism

Court catalogs schools' violent crimes

'Beauty of Beijing's alleys akin to a wise, old person'

China makes progress fighting domestic, international cyber crime

US Weekly

|

|