The unkindest cut of all in the name of beauty

Updated: 2015-04-14 08:03

By Zhang Yi(China Daily)

|

||||||||

Demand for cosmetic surgery is booming across Asia, especially in China. However, for some patients the fleeting dream of physical perfection has turned into a prolonged nightmare, as Zhang Yi reports.

Every year, thousands of Chinese women travel to South Korea for plastic surgery in the hope it will produce the "perfect" appearance and transform their lives.

For some, their wishes are granted, but many find themselves distraught, lacking confidence and even suicidal as a result of badly performed operations and the side effects of the medication they have been prescribed.

Now, three of those women have banded together to raise awareness and warn potential patients of the risks they may face if they choose to go ahead with the procedures.

The women said they feel they were duped, and the deception is almost as hard to bear as the pain they suffer every day because of their disfigured faces.

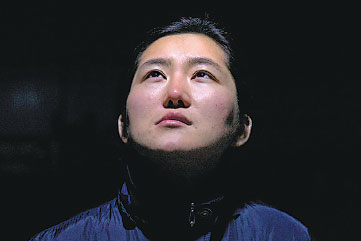

Jin Weikun, 27, a professional style consultant, said she had been reduced to the status of a laboratory mouse after a series of failed operations, including "face contouring" and two procedures to alter the shape and size of her breasts.

Jin originally had breast reduction surgery at a clinic in Taiyuan, her hometown in Shanxi province, but was unhappy with the results because she felt the surgeons had left her breasts asymmetrical. When she complained, the clinic said it was unable to repair the "damage".

Jin researched operations designed to rectify asymmetric breasts, but was wary of proceeding because of the risks involved. However, her hopes were rekindled when she saw Bucket List, a TV show aired by KBS, South Korea's national broadcaster, which told the story of a woman who had successfully undergone surgery to correct a botched breast operation.

In late 2013, Jin saw ads canvassing participants for a purported sequel, Bucket List 2. The producers, who claimed to be working in association with Shanghai Television and clinics including JW Plastic Surgery Korea, were offering free surgery to 24 people unhappy with previous cosmetic procedures. Jin was convinced that the show would provide an opportunity to have the surgery that would turn her life around again.

Deception and sham

"Talking with the head of the JW clinic, I believed it had top-notch cosmetic techniques, and in January last year I flew to Seoul with 16 or so other women. I went ahead with the breast surgery, plus a further 12 operations on my face (at the insistence of the program's producers), based on the trust I placed in the show's recommendations for the clinic. That all turned out to be a sham.

"About a month after the surgery, when I began to feel everything was totally disorganized, I called Shanghai Television only to be told that they'd never heard of the show. The surgery on my breasts was a failure, my chin was lopsided, and an implant in my nose had been placed incorrectly."

The clinic rejected Jin's claims, saying the operations went well. The breast surgery had been successful, it said, and the lopsided chin was the result of an imbalance of soft tissue in Jin's face, rather than bone damage sustained during surgery.

Ge Lijun, a spokeswoman for JW Plastic Surgery Korea, confirmed the clinic had taken part in Bucket List 2, but she refused to vouch for the authenticity of the program. She claimed the show had been broadcast by a cable channel affiliated with STV, but that the Shanghai station had not commissioned it.

The clinic said it always advises potential patients to be cautious when mulling plastic surgery, to consult family members before making a decision, and to be prepared to accept the changes that will be made to their bodies.

Jin said she wonders if she was naive to believe the bona fides of TV programs she had regarded as documentaries, but which she now believes are essentially advertisements.

"I partly blame myself for making this reckless decision. I have discovered about 200 other Chinese women who have gone through similar things in South Korea, and I know that many faces have been ruined by the deficiencies in some clinics and by illegal operations in others, and also by unscrupulous medical brokers."

Crackdown commences

In February, the South Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare announced a crackdown on illegal brokers and unregistered clinics, following a series of cases involving accidents with plastic surgery, including that of a 50-year-old Chinese woman who was declared brain dead after she had surgery on her eyes and nose in the prosperous Gangnam district of the South Korean capital.

The ministry adopted a series of measures in response to the rising number of complaints, many of them made by female "medical tourists" from China, about botched operations and exorbitant charges.

"Market-disturbing activities involving illegal brokers and inflated fees, as well as disputes over malpractice, are sparking complaints from foreign patients," the ministry said in a statement.

In 2013, more than 25,400 Chinese, mostly women, traveled to South Korea for cosmetic procedures, an increase of 70 percent on the previous year, with each patient spending an average of $3,150 on the surgery, according to the ministry.

The new measures require all medical practices that deal with foreign patients - and any brokers they use to attract those clients - to register with the ministry. Those who fail to do so are liable to a hefty fine and, in the worst cases, a prison term of up to three years.

However, many former patients have complained that the measures do almost nothing to help them obtain remedies, physical or financial.

Mi Yuanyuan, 39, a company CEO from Zhejiang province who lived in South Korea for a number of years, had never considered plastic surgery until she watched a TV show called Let Me, in which a number of "ugly" faces were turned into "attractive" ones. Having seen the show, she approached the clinic where the women were treated.

"I was a natural beauty, and I always received compliments about my appearance, but I went to the clinic because I was curious about how a face could be perfect. In September 2013, I was advised to have an operation to make my flat nose more pointed and to have my hairline lowered. That's when my tragedy began.

"It ended up costing me 70,000 yuan ($11,300) and the subsequent operations to repair the faults in December of the same year failed too. I now have an obvious 20-centimeter scar on my forehead. The most horrible aftereffect is that hair at the front of my head has stopped growing, and now I have to wear a hat all the time."

Legal quandary

Mi said her demands for compensation were refused, and one of the clinic's staff members poured noodle soup over her during a heated discussion.

"If I took legal action I would need to hire a Korean lawyer and an interpreter. And even if I did that, leaving aside the cost, I doubt I would get a fair hearing in court because the cosmetic surgery industry generates huge amounts of revenue for the country."

Wei Jie, a partner at the Jieqiang law firm in Beijing, said compensation cases for failed plastic surgery take years to settle, partly because of the complexity of the legal process but also because of a lack of agreed standards on what constitutes successful surgery. Even if the plaintiffs are successful, the travel and legal costs are extremely onerous, he said.

"It's really hard for individuals to instigate cross-border legal proceedings, given the geographical distance, language barriers and the question of obtaining evidence," he said.

Mi advised people considering traveling overseas for cosmetic surgery to think twice, and said they should be particularly skeptical about so-called true stories on popular TV shows, because the side effects of surgery can easily be glossed over with carefully applied make-up and clever filming techniques.

In 2010, Chen Yili, 33, a businesswoman in Shenzhen, Guangdong province, spent more than 170,000 yuan on a string of operations on her jaw, lips and nose at a clinic in Seoul that had been recommended by a medical broker.

After returning to China, she began to have nasal infections and flu-like symptoms in her nose that still persist nearly five years after the procedures were carried out.

"I can't go to sleep without pills, I can't meet friends, and I'm depressed," she said, adding that sometimes she needs to take 12 antidepressant tablets a day.

She also warned of illegal brokers who exaggerate the benefits of surgery, and of exorbitant costs - about 30 percent of the fee goes to the broker: "Profits are placed ahead of health and safety. The brokers are always after money, and they will do or say anything to get people to have costly operations."

The Korean Health Industry Development Institute said more than 1,000 legal agencies have registered with it, but estimated that illegal agencies hold about 87 percent of the plastic surgery market and they aggressively target customers from overseas.

Zhang Bin, chairman of the Chinese Association of Plastics and Aesthetics, said the problem has a global dimension, and Chinese who choose to have plastic surgery in South Korea usually hire an agent to act as a liaison between customers and clinics, which can result in people being taken to unlicensed clinics.

"Lax regulations, inadequate facilities and unqualified surgeons, some of whom are barely physicians, are the primary reasons for the failed surgery," he said.

CAPA said it's working with its counterparts in South Korea to establish a database of fully licensed Korean surgeons to prevent patients from falling foul of unscrupulous practitioners.

Zhang said the database, which will list about 1,500 surgeons, will be published in Chinese so potential patients will be able to check their surgeon's educational background and medical qualifications.

As Jin, Chen and Mi continue to seek redress and, hopefully, to protect others from a similar fate, they said the deception they encountered in their quests for physical perfection was the unkindest cut.

For all three, the physical scars are still raw, and when Chen considers the persistent numbness in her jaw, she knows it's something she will have to live with for the rest of her life.

Frustrated in her efforts to obtain restitution and compensation, Mi claimed the clinic had made a number of serious, but unfounded, accusations against her online in the hope of undermining her veracity. She said she wants nothing more than a sincere apology and hoped the clinic would accept a measure of responsibility.

Jin hopes her story will provide a salutary lesson for those considering cosmetic surgery, and has volunteered to become the lead organizer of a group of about 200 people who have undergone similar experiences.

"After everything I've been through, I need to do something more meaningful than just pursuing good looks," she said.

Contact the writer at zhang_yi@chinadaily.com.cn

|

Women who say they have been left disfigured by shoddy procedures in South Korea wait in a room at a clinic in Beijing. Fred Dufour / AFP |

|

Mi Yuanyuan.a company CEO from Zhejiang province, has a long scar on her forehead and has experienced other side effects after cosmetic surgery in a clinic in South Korea in 2013. |

|

Jin Weikun, who had unsuccessful plastic surgery in South Korea, hopes her story will provide a lesson for potential patients. Photos by Feng Zhonghao / for China Daily |

(China Daily USA 04/14/2015 page7)

Ex-student sought in shooting death of North Carolina college

Ex-student sought in shooting death of North Carolina college

Women in politics - Hillary Clinton is just one of them

Women in politics - Hillary Clinton is just one of them

10 Red Dot Award winning carmakers in '14

10 Red Dot Award winning carmakers in '14

Get a birthday cake for your pets

Get a birthday cake for your pets

7 ways to beat 'spring sleepiness'

7 ways to beat 'spring sleepiness'

Legendary painting of Mona Lisa recreated

Legendary painting of Mona Lisa recreated

National festival underway with cherry blossoms in peak bloom

National festival underway with cherry blossoms in peak bloom

Ten photos you don't wanna miss - April 13

Ten photos you don't wanna miss - April 13

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

US to help smart

cities quest

Clinton's win not guaranteed despite global celebrity

US has record number of applications for H-1B tech visas

China's slow down has upside

US voluntary medical team funded for China trip

Hilary Clinton launches

presidential campaign

'No room' for election China-bashing: US politicians

AVIC buys Calif. aviation parts distributor

US Weekly

|

|