Lessons of the Opium War

Updated: 2012-02-24 08:41

By Andrew Moody (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

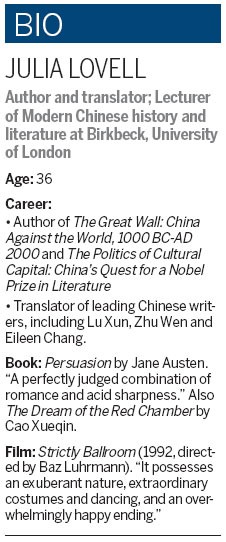

Julia Lovell believes much of the impetus behind China's transformation in recent years comes from the fear of falling behind. Nick J B Moore / China Daily |

Acclaimed writer says she had to revise almost every assumption about Chinese empire

Julia Lovell says the Opium War still leaves a lasting mark and casts a shadow on China even today.

The 36-year-old China historian, who has just written a book on the 19th century conflict between Britain and China, Opium War, Drugs, Dreams and the Making of China, says the war certainly teaches those in modern China of the dangers of falling behind the West.

"If you talk to many Chinese about the Opium War, a phrase you will quickly hear is luo hou jiu yao ai da, which literally means that if you are backward you will take a beating," she says.

"So the events of the Opium War are still held up as a tragic reminder of what happens if China shuts its doors to the outside world."

Lovell, who is perched in the junior common room at Queen's College, Cambridge, surrounded by dark 18th century portraits, believes much of the impetus behind China's transformation in recent years comes from the fear of falling behind again.

"They have very strong echoes in the present day in a China which in the past 30 years has very energetically embarked on a process of ... opening itself out to political, economic and cultural global influences," she says.

The war, which is largely forgotten in Britain and elsewhere, remains a seminal moment in Chinese history.

Britain, controversially, even at the time, used its then state-of-the-art navy against primitive Chinese warships to secure trade passages into China for its lucrative opium trade. The conflict eventually led to most of China's major ports being ceded to foreign powers.

"I think so much of the tragedy comes from the dramatic and terrible discrepancy in firepower between the British and the Chinese and as a result of that thousands of Chinese died in terrifying ways," she says.

"They either burnt to death or they committed suicide because they were terrified by these foreign invaders whose language and intentions they couldn't understand."

The book, Lovell's third on China, is shortly to be published in Chinese, and took her three years to produce, including spells in China reading through many contemporary Chinese documents of the time. It focuses in detail on the first Opium War (1839-1942), but also deals with the second (1856-60) as part of the aftermath of the initial conflict.

"I noted that many historians had written wonderfully about the Opium War before but that Chinese historians tended to focus on Chinese sources and Western historians on European or American sources. There was relatively little overlap and what I wanted to do was provide an English account of both sides of the story," she says.

The book, which runs to nearly 400 pages, is written in Lovell's often wry and witty style as she demonstrated in an earlier book on the history of the Great Wall.

As such it has proved a word-of-mouth success among those wanting to delve deeper into Chinese history.

"It has been well received. Whether it has moved on from being a book about China to being something greater than that we will have to see," she says.

The Opium War was very much a clash of civilizations. The British, with the East India Company at the vanguard, effectively sold opium to China in the early 19th century in exchange for tea, for which it had developed an unquenchable thirst.

The Chinese authorities, worried about growing addiction, banned the trade, leading to military conflict.

The first Opium War ended with the Treaty of Nanking in 1842 ceding Hong Kong to Britain.

Some of the events in Lovell's book read like a comedy, rather than a military conflict, with many of the key participants not fully understanding what was going on.

Various emissaries during the various key battles sent back reports to the then Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) emperor Daoguang informing him of great victories when, in fact, major defeats had occurred.

"The reality was that the further away you were from Beijing the freer the rein you had. It was really quite flabbergasting how fast and loose some of the emperor's servants played with the truth," she says.

Lovell says the war uncovered just how disunited China was at the time with the Qing Dynasty, the result of a Manchu invasion, being ethnically different from the majority Han Chinese population.

She says this was never more in evidence than when Canton (the modern city of Guangzhou) was under siege by the British in 1841.

"The city is full of Chinese, all drawn from different provinces in China, and they are too busy fighting each other to put up a coherent fight against the British. I was struck by how complex this place we call China is. Writing this book really caused me to revise almost every assumption I had before about the Chinese empire."

Lovell, the daughter of music teachers, was born in Cumbria in the extreme northwest of England but lived in many parts of the country.

She went on to read history at Cambridge but switched disciplines after the first year to Chinese partly because she was inspired by James Bond who in You Only Live Twice (the film and not the book) revealed he had read oriental languages at the same university.

"I remember seeing the film in the Christmas holiday when I was considering changing subject and I thought it would be a good cocktail party anecdote if I changed subject because I wanted something in common with James Bond," she recalls.

To build her language skills, she went on to study Chinese at the Johns Hopkins Center for Chinese at Nanjing University.

"It was very important for me to spend that nine months in China as an immersion in the language," she says.

She returned to Cambridge to do a PhD and became a research fellow before taking up her current role as a lecturer of modern Chinese history and literature at Birkbeck, the University of London.

Lovell has a worldwide reputation as translator and has translated many leading writers into English, including Lu Xun, the leading Chinese writer of the early 20th century and more modern writers like Zhu Wen. She has also translated Eileen Chang's Lust, Caution, on which a major film was based.

The Chinese have very different concepts about history, as Lovell has discovered in her other role as a historian.

"I think it is true on China that even on an everyday level ordinary people are used to conjuring up a wide range of historical analogies. This familiarity with history has no analogue in Britain, for example," she says.

She found while sitting in on history classes at schools and universities in China doing research for her book, there were diverse opinions about the Opium War.

"I was struck that although much of the teaching is framed to blame the conflict, very correctly, on British aggression and misconduct, many of the responses from children in the classrooms were strikingly critical of the Chinese themselves."

Relief reaches isolated village

Relief reaches isolated village

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Earth Day marked around the world

Earth Day marked around the world

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Chinese fleet drives out Japan's boats from Diaoyu

Health new priority for quake zone

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

Russia criticizes US reports on human rights

China, ROK criticize visits to shrine

Sino-US shared interests emphasized

China 'aims to share its dream with world'

Chinese president appoints 5 new ambassadors

US Weekly

|

|