Revolutionary recipes

Updated: 2012-04-20 07:56

By Kelly Chung Dawson (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

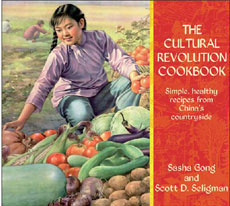

The Cultural Revolution Cookbook has risen to No 1 in Amazon's Chinese cookbook category. Provided to China Daily |

New book serves up delicious dishes from a difficult time

The years of the "cultural revolution" (1966-76) are often associated with scarce food supplies, a time when many people struggled to put dinner on the table.

Chairman Mao Zedong himself famously declared that a revolution is not a "dinner party", and most citizens who have lived through that time would likely agree.

But a new book titled The Cultural Revolution Cookbook argues that those exact conditions drove people to create filling, healthy dishes with the most simple ingredients.

"We realized that what was born out of necessity as the result of a lack of ingredients could actually be viewed as desirable in 21st century America - the idea of eating locally grown produce, eating fresh food and using the most basic, unprocessed ingredients," co-author Scott D. Seligman says.

"It's simple country cooking, and people are interested in that today."

The book only uses ingredients that can be found at standard American grocery stores, Seligman says. Tofu, vinegar and soy sauce are the only processed foods in the book. Since publication in December, a first edition has sold out and the book has risen to No 1 in Amazon's Chinese cookbook category.

Time magazine's Daven Wu described the book as "a beautifully illustrated cookbook that documents the indomitable spirit of a people whose defining greeting is still, 'Have you eaten yet?'"

"We weren't prepared for the huge response we've received," Seligman says. "People like Chinese food, but what surprised me is that people seem to feel that Chinese food is hard to make. These recipes are so simple."

Seligman and co-author Sasha Gong are long-time collaborators, having worked on Gong's autobiography Born American and other projects and articles. Seligman has written several books on China including Chinese Business Etiquette, and Dealing with the Chinese.

During work sessions, the pair frequently take breaks for lunch, Seligman says. After working together for some time, Seligman soon realized that Gong's cooking was different typical Chinese restaurant fare, he says.

"When Scott first suggested the idea of a book based on 'cultural revolution'-era recipes, I said, 'Are you nuts?' People didn't have enough to eat during that time," Gong says. "But the more I thought about it, the more I realized that if we could incorporate the stories of Chinese history in the book, it would be fun and very educational."

Gong, who was born in Guangzhou, capital of Guangdong province, learned to cook at the age of 6 because her parents worked long hours, she says. Later, when her parents were sent to the countryside for "re-education", she and her siblings had very limited access to food, she says.

"As children, we had to take care of each other," she says. "Everything except for vegetables was rationed, so we learned how to plan our meals carefully, and how to make the most of what we had."

|

Sasha Gong and Scott D. Seligman, co-authors of the book. Provided to China Daily |

Cooking was among the few enjoyable activities in those days, she says. "I found satisfaction in making simple dishes. Cooking is a very creative process, and in the way I grew up, I didn't really have room to be creative in any other areas of my life."

Her memories of cooking and eating with her family are extremely positive, she says. As a self-proclaimed "history nerd" and sociologist who has taught at UCLA and George Washington University, Gong says that a country's food and eating culture reflects its values.

"Food is a major bond that holds society together," she says. "Eating is both social and personal. Chinese food culture focuses on family, personal loyalty, generosity and friendship. There are many differences between Chinese and Western-style eating. One example is the Chinese style of sharing food."

The Chinese emphasis on giving the best parts of the dish to the older members of the family is also indicative of Eastern values, she says.

The book's 59 recipes are accompanied by colorful stories about Chinese history and the background of each dish.

A vinegar-glazed cabbage dish is paired with the story of The East is Red, a famous rallying song of the era. The tune was originally a peasant ode to cabbage hearts, before being rewritten to honor Chairman Mao.

A potato dish is accompanied by the story of Nikita Khrushchev's "goulash communism", a phrase popularized when he made the comment that if the former Soviet Union promised only revolution, "they'd ask if it's not better just to have good goulash". Chairman Mao took this as a weakening of resolve. Chinese translators of the time, lacking an appropriate word for goulash, chose "potato and beef stew" as an alternative.

|

Shallow-fried potato shreds, one of the 59 dishes introduced in the book. Provided to China Daily |

"Beef was scarce in China in the 1960s, so goulash was not really much of an option," the cookbook says. "But everyone enjoyed fried potato shreds."

Beautiful color photographs of the dishes are the result of three food-filled days in which Seligman and Gong cooked every single meal in the book, he says. Neighbors and friends joined as the pair prepared dishes for the photographs.

Gong hopes that American audiences will come away with a sense of the endurance of the Chinese people.

"We can overcome anything, and at the very least, we came away with some seriously good recipes and a good sense of humor."

kdawson@chinadailyusa.com

Relief reaches isolated village

Relief reaches isolated village

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Earth Day marked around the world

Earth Day marked around the world

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Chinese fleet drives out Japan's boats from Diaoyu

Health new priority for quake zone

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

Russia criticizes US reports on human rights

China, ROK criticize visits to shrine

Sino-US shared interests emphasized

China 'aims to share its dream with world'

Chinese president appoints 5 new ambassadors

US Weekly

|

|