China needs to change trade strategy

Updated: 2012-06-01 09:12

By Siva Yam and Paul Nash (China Daily)

|

||||||||

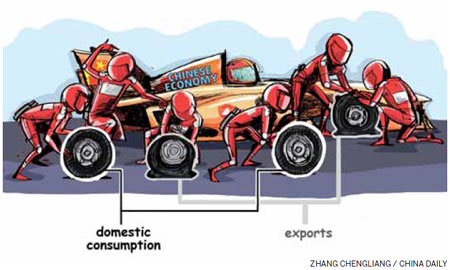

Country cannot rely on old pillars to prop up economy

For several decades, China has built its economic strategy on four pillars: exports, foreign direct investment, fixed-asset investment and domestic consumption. Of these, exports have played a vital role - they have drawn in FDI, underpinned investment in fixed assets and fueled domestic consumption.

Since the global financial crisis, China's exports to its two largest customers - Europe and the United States - have slowed down significantly, giving a new sense of urgency to the government's current plan to lift the nation's manufacturing base up the value chain.

When China embarked on its industrial export drive in 1976, it had little capital, technology or experience. It also had few foreign distribution channels and virtually no money for R&D. Chinese manufacturers therefore had to rely on a strategy known as the "Three Supplies". Foreign companies supplied materials, samples or parts; Chinese companies processed, copied or assembled. This strategy allowed China to build capital quickly and cheaply. It minimized R&D expense and created millions of jobs in China, even though most paid less than $100 a month.

To render its goods affordable, China helped its manufacturers minimize costs, at least initially. It offered them land, tax holidays, rebates on exported manufactured goods, and reduced import duties on equipment used to produce exports. It also encouraged manufacturing that draws on the comparative advantage of the country's immense labor pool.

As inexpensive Chinese products flooded the world market, they dampened inflation and put downward pressure on interest rates. The Chinese government reinvested its gains in US Treasury securities to bolster the dollar, forcing rates lower. Coupled with innovative financial engineering by institutions in the United States, Western consumers saw the value of their assets appreciate and they leveraged their spending accordingly.

China's export machine pulled in unprecedented FDI as American and European companies hastened to outsource their manufacturing to China. As exports and FDI escalated, investment in capital assets and infrastructure grew uncontrollably. Land prices skyrocketed as developers procured cheap land by promising to foot the bill for infrastructure around their properties. Factories, theme parks, hotels and shopping malls sprung up all over.

The problem, of course, is that many of these projects were undertaken without proper economic justification, and they have now resulted in significant excess capacity.

To keep their factories running since the global financial crisis, Chinese manufacturers have been cranking out products that are not being sold or sold at or below cost. Many have been able to report strong earnings by manipulating inflated land values. Some leverage their land's value by borrowing against it to invest in other real estate projects. All the while, China continues to import enormously to maintain its basic manufacturing sector for when the global economy recovers.

China's export machine ran into trouble when the US housing bubble burst and the world plummeted into recession. Built on a strategy that aimed to dominate the global marketplace in low-value-added products, it may not return to its former scale anytime soon. European and American consumers are trying to deleverage. Moreover, since only a handful of Chinese brands - Haier Home Appliances and Lenovo - are recognized overseas, most Chinese products remain at the mercy of importers, who leave Chinese manufacturers with very little margin.

Unlike Japan and South Korea, which have moved up the value chain, Chinese companies are still struggling to develop their technological and marketing capabilities. Chinese factories have remained complacent for too long, preferring OEM contracting to significant investment in R&D or engineering. The long-term consequences are obvious - they are illustrated, for example, by the continued inability of Chinese automakers to sell into the US.

With European and American companies are still struggling and consumer demand soft, FDI into China has declined. Some FDI still comes from big Western companies with well-established positions in the consumer market, such as GM, VW and Samsung. Overseas Chinese or ethnic Chinese in Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore and Malaysia continue to speculate in real estate, buying up prime industrial parcels in places such as Guangdong, forcing foreign companies wishing to enter or expand at a reasonable cost to look to the interior, which is comparatively less attractive.

The other two pillars of China's economic strategy still stand. Investment in fixed assets continues, particularly in infrastructure projects funded by the nation's huge foreign currency reserves. Some of these projects, however, have no economic basis, and their eventual failure will impair the Chinese economy over time.

China's domestic consumption has expanded substantially since the late 1970s, but the average wage is still relatively low. While wages are rising, they are translating into increased manufacturing costs. China's affluent spend, but they spend largely on foreign goods. Many domestically manufactured goods, apart from those with uniquely Chinese or patriotic appeal, now wind up on the open global market awaiting buyers or disposal.

The Chinese government has responded with new policies aimed at changing domestic consumption. Government officials, for example, are now asked to buy only domestically-made vehicles. The State Council has also announced new subsidies on domestically-made appliances and autos. But it will take time for these policies to have an effect, particularly in a society where the status associated with owning foreign-made luxury goods is considered a symbol of progress at the expense of practicality.

There are signs that the US economy is recovering, which is clearly good news for China. But China's trade strategy is overshadowed by unprecedented challenges. Going forward, Chinese manufacturers will find it increasingly difficult to rely on strong overseas demand, favorable government policies and low-cost labor. Since the country already dominates the world market in low-value-added, commodity-type goods, it will have to enter into the proprietary, higher-value-added arena.

China made extensive investment in fixed assets throughout the global downturn, but it knows that such investment will not be able to fund growth indefinitely. Chinese companies will have to "go out" to compete, developing their own global brands and technology. They will have to alter their structure to become true multinational corporations rather than simply OEM contractors.

China recognizes that in order to compete internationally the country has to shift to technologically advanced manufacturing. Precision and reliability are essential to many of the new products that China wishes to sell overseas, especially those that must meet stringent safety standards. Branding and R&D activity will have to improve, and factories will have to incorporate more automation.

The legal and economic reform process also has to move forward with renewed urgency - to deepen transparency and foster a stable, consistent legal system. It must encourage the separation of guanxi (personal relationships) from business to foster an environment in which decisions are made based on sound economic rationale.

It is unrealistic, of course, to expect Chinese culture to change overnight. But by taking confident strides, China aims to instill confidence, both in its own citizens and in foreign investors. As this happens, it will become easier for China to acquire the skills and technologies it needs to carry it to the next stage of development, as well as for foreign companies to reinvigorate their operations in China. In the end, both Western countries and China can only benefit.

Siva Yam is president of the US-China Chamber of Commerce and an advisory council member of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago. Paul Nash is an investment analyst in Toronto and editor of China Alert. The views do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.

(China Daily 06/01/2012 page9)

Relief reaches isolated village

Relief reaches isolated village

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Earth Day marked around the world

Earth Day marked around the world

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Chinese fleet drives out Japan's boats from Diaoyu

Health new priority for quake zone

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

Russia criticizes US reports on human rights

China, ROK criticize visits to shrine

Sino-US shared interests emphasized

China 'aims to share its dream with world'

Chinese president appoints 5 new ambassadors

US Weekly

|

|