The art of making the right moves

Updated: 2012-06-15 08:49

By Kelly Chung Dawson (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

Tom Doctoroff attempts to decode the Chinese psyche in his book What Chinese Want: Culture, Communism and China's Modern Consumer. Provided to China Daily |

Understanding local culture crucial for marketing campaigns in China, advertising executive says

Americans are often confronted with contradictory visions of China - a modern machine that will level US industry, or an unthinkably large population of backward, rural bumpkins who toil in dusty servitude.

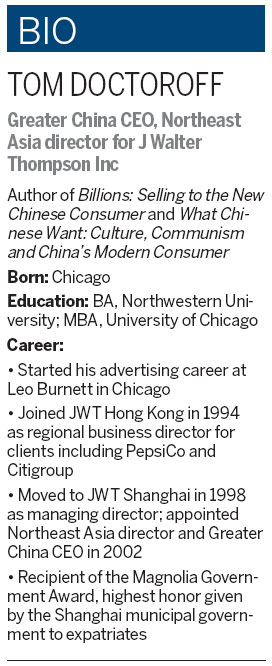

But the most common misconception is that the Chinese path to modernization ultimately leads to a future that will be recognized as Western, an expectation that ignores deeply rooted differences spanning thousands of years, says Tom Doctoroff, an advertising executive and author of the book What Chinese Want: Culture, Communism and China's Modern Consumer.

"As China becomes more international, Westerners think that it is becoming more like America, and that simply isn't true," Doctoroff says. "Until we recognize that the Chinese world view is fundamentally different from our own, there will continue to be misunderstandings between us."

Doctoroff, Greater China CEO for ad agency J Walter Thompson, has spent 14 years in China. His 2007 book, Billions: Selling to the New Chinese Consumer, also attempted to guide Western advertisers, but his latest is an effort to decode the Chinese psyche, he says.

"The Chinese world view, not to mention its brandscape, differs profoundly from other markets," he writes. "I have not encountered a single brand that did not require significant modification to positioning and marketing before it succeeds in China. This, of course, does not preclude the feasibility of a global brand idea - Nike should breathe a 'Just Do It' spirit everywhere. But, to maximize relevance and trigger loyalty that results in a sustainable price premium, global brands must appreciate Chinese cultural and operational realities."

New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg, speaking at the book's launch party in Manhattan in late May, called What Chinese Want extremely timely.

"Tom has really written an important book," Bloomberg said. "I keep saying in this city that people keep blaming China for every mistake we make instead of looking in the mirror. In the end, if we get our act together, China is the market for us. We really do have an interest in understanding what's going on over on the other side of the world."

Although Doctoroff's target audience is Western businesspeople, he believes anyone with an interest in learning what motivates the Chinese will find his book useful. "Particularly for businesspeople, as they get into collaborations they should have a deeper understanding that how Chinese individuals engage with organizations and society is very different from us," he says.

Too many Western companies come to China with hopes of applying business strategies that have worked elsewhere, Doctoroff argues. An understanding of Chinese culture is crucial to correctly identifying an appropriate campaign for a given market.

"Chinese rulers derive legitimacy from their assumed mastery of the system, so the worst sin a foreigner can commit is teaching," he writes.

Doctoroff is confident that he can identify recurring themes and conflicts that define Chinese culture.

He believes the behavior of Chinese consumers is dictated by a fundamentally Confucian conflict between self-protection and status projection. The average Chinese buyer will spend more money on a product that is publicly consumed; this explains the popularity of multinational brands of clothes, cars and other goods that easily connote status. In contrast, Chinese companies dominate the market for home appliances and other privately consumed items.

"In China, 'face' is fundamental, because public acknowledgment is the currency of forward movement," Doctoroff says. "Face is a major driver in Chinese society."

Marketing strategies that appeal only to the individual's desire to indulge will fail, he says. The payoff should be practical and external. For example, a spa shouldn't be marketed as a means of relaxation but for recharging one's batteries.

"Companies miss this basic public-consumption imperative, and they not only make mistakes in positioning but also in their pricing strategies," he says.

Additionally, Westerners should avoid the mistake of assuming that, as China has modernized, its public has become more individualistic, Doctoroff says.

"Western companies assume that as the Chinese become more modern, they will be more rebellious and want to define themselves separate from society," he says. "But in China the basic unit is family, not the individual. Chinese people as individuals have strong egos but are not eager to challenge convention."

While the rapid change of recent decades has produced generation gaps, Doctoroff doesn't believe there has been a fundamental break between age groups. "When Westerners talk about the gap, they are talking about rebellion, but in China it is only a gap of experience and perspective."

The tension between desire for upward mobility and fear-based conformity is apparent in all facets of Chinese life, and stability is prized above all, he writes. Although Chinese art and music have caught on with international audiences in recent years, Doctoroff says the country at present doesn't cultivate an environment in which innovation can flourish.

"It starts from the education system, so I think it is a long time away," he says. "I would never say never, but you cannot just promote innovation and expect that it will magically just happen. I don't think that the seeds of mold-breaking innovation have been planted yet."

Commercial innovation has always been a question of top-down diktat, as opposed to bottom-up entrepreneurial self-expression, he writes. For this reason he doesn't expect Chinese companies will have much success in marketing to US consumers in the foreseeable future.

However, he is highly optimistic about Chinese development and the US-China relationship.

"There are a lot of people in the West who are genuinely interested in the rise of a complementary value system that represents a different center of gravity," he says. "I think people are being confronted with the reality of China's rise, and it is forcing them to challenge their assumptions about the course of economic development and what that means for culture. Most Westerners still think China is going to become more like us, so it is a slow persuasion process."

Doctoroff senses an "affectionate defensiveness" on the part of Chinese toward American culture.

"I call the relationship between the US and China a 'dangerous love'," he says. "I think that Chinese people are very fond of America but also very sensitive to any perceived indignity. But there is no question that China and the US are natural allies, on a people-to-people level."

As Western companies make inroads in China, international brands will continue to provide a sense of identity to many Chinese, he says. "Brand affiliation is one of the freest forms of identity and it has an extremely powerful effect on Chinese society," he says. "But ultimately it will never be strong enough to truly influence the Chinese cultural DNA."

kdawson@chinadailyusa.com

(China Daily 06/15/2012 page24)

Relief reaches isolated village

Relief reaches isolated village

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Earth Day marked around the world

Earth Day marked around the world

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Chinese fleet drives out Japan's boats from Diaoyu

Health new priority for quake zone

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

Russia criticizes US reports on human rights

China, ROK criticize visits to shrine

Sino-US shared interests emphasized

China 'aims to share its dream with world'

Chinese president appoints 5 new ambassadors

US Weekly

|

|