Where winds tend the vines

Updated: 2012-11-18 08:01

By Katie Parla (The New York Times)

|

||||||||

|

The main town on Bozcaada is isolated but cultured, providing safety for residents from overdevelopment. Photos provided to China Daily |

|

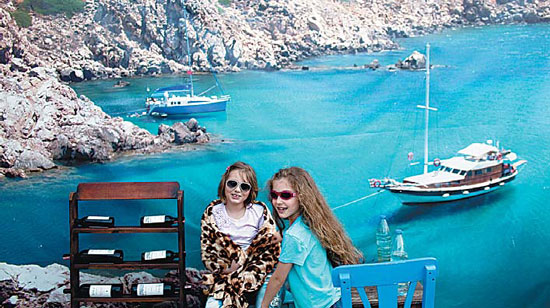

Girls play in front of a poster of a cafe, which presents a local landscape of the blue sea. |

|

Fishermen fix their nets, preparing for another day on the Aegean. |

There is an island in Turkey that beckons with images of idyllic life scented with ripe fruit and herbs and colored with the bright blue of sea and sky. Katie Parla takes us there.

An image can call to mind a place, and occasionally a sound does, too. And, of course, so do scents. One enduring memory of my trip to Bozcaada (known to the Greeks as Tenedos), an island off the western coast of Turkey, is the aroma of maturing figs, lavender and rosemary carried by persistent winds that locals say help shape the island's character.

Funneled through the Dardanelles, which connects the Sea of Marmara to the Aegean, the winds repel all but the most committed travelers in the winter and attract small numbers of them in the spring and summer. And they help create an environment far different from the mainland: breezy, pleasantly warm and dry, ideal for cultivating grapes.

That means that this 24-square-kilometer island - a seven-hour trip from Istanbul by bus and ferry - offers solitude with a dash of culture in its only town, also called Bozcaada, and vineyards, whose output has helped make this one of Turkey's most promising wine destinations.

"It is the special climate on the island that makes a great red wine," says Hermann Gareis, who started the newest vineyard on the island, Amadeus, just west of the town in 2010.

His is one of many vineyards that undulate from the edge of town to the coasts, interrupted by occasional clusters of houses or a hotel. Most residents produce their own wine in small batches and, despite obstacles to commercial production - a dearth of labor, high taxes on alcohol and distant wine-drinking cities - several producers are turning out excellent wines.

Amadeus is gaining a toehold. Under the tutelage of an Italian enologist, Gareis and his son, Oliver, planted several vineyards across the island, then opened a winery in 2010 that turned out 14,000 bottles that year. They more than tripled that number with the 2011 harvest.

Their biggest success has been with cabernet sauvignon, and thanks to Bozcaada's terroir - "the earth was made to produce wine," Gareis says - they have continued to expand.

"We started experimenting with gamay," he says of a more fickle grape variety for this climate. "The grapes were good. The wine had some mistakes, but we kept trying."

He is attempting to follow in the footsteps of Corvus, the most prestigious producer on the island, indeed in all of Turkey.

Founded in 2002 by Resit Soley, an Istanbul architect and part-time island resident, Corvus introduced modern wine-producing techniques to the island, as well as a number of international varieties. Today, the winery turns out more than 20 different wines and has earned international acclaim.

But Corvus did not make Bozcaada famous. The island has a past much grander than its modest stature and population suggest. Its strategic location in the Aegean, close to the entrance to the Dardanelles, meant that Bozcaada was often contested land.

What remains after hundreds of years of conflict is a village trimmed by two crescent-shaped ports and flanked by a honey-colored Ottoman fortress, one of the best preserved in the Aegean. The town center is divided into Greek and Turkish sections, referring to the groups who originally built the districts.

The Turkish area, a warren of houses built into an uneven slope, is mainly residential, though small hotels and shops have begun to crop up. I spent most of my evenings on the island dining and drinking in the grid-planned Greek area, where wooden homes have been converted into boutique hotels, pensions, restaurants and art galleries.

One studio and cafe, Deniz, had just opened last June when I was there. Its owner, Deniz Barlas, first came to Bozcaada in 2000, when the ferries were battered World War II-era ships. "It was New Year's, it was miserable, we got stranded, and I loved it," she says.

In the years that followed, Barlas made frequent trips back to the island. In 2009, she left her job as an advertising executive in Istanbul and moved to Bozcaada to pursue her dream of living a life filled with art and nature. Her store does double duty as an atelier where she paints and a cafe where she serves homemade pastries in a lavender-filled garden.

The wind, she says, provides both inspiration and safety from overdevelopment.

"The island is never still - you feel like you are sailing," she says.

The island's agrarian landscape, though, puts it firmly on land.

Summer abundance is preserved in a traditional tomato jam produced by the Salto company, run by one of the few Greek families left on the island.

At Maya, a restaurant and working farm, the chef and owner, Selcuk Aykan, makes marmalades and preserves from the figs, apricots and quinces he grows on his property and buys at the local farmers' market.

In 2010, Aykan expanded his food production to include artisanal goat cheeses, which he serves to diners at a cluster of four tables in his front yard. He moved to the island in 2006, drawn by its atmosphere.

"This is like no other place in the world," he says. "Bozcaada is like a big anchored ship. You can see the sea from everywhere."

He said he also appreciated a general lack of development on the island.

"In a five-minute drive you are isolated," he says. "All the small beaches become your own. All you need is an umbrella and an icebox."

Indeed, on several excursions I found beaches deserted or nearly empty.

The New York Times Syndicate

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|